“Cuba would have to invest roughly $33 billion over 15 years to 2030 to achieve these targets of 10 million tourists,” the Brookings Institution, a U.S. think tank, estimated recently in a report that takes a careful look at the tourism sector on the island.

“Tourism in Cuba. Riding the Wave toward Sustainable Prosperity,” by Richard E. Feinberg and Richard S. Newfarmer, describes that figure as massive compared to the total size of the Cuban economy (some 87 billion dollars). “It seems unlikely that sufficient financing and domestic savings would be available to reach Cuba’s ambitious goals.”

Feinberg, a researcher of the Latin American Initiative, of the Brooking Institution’s study center, and Newfarmer, professor of the London School of Economics, described the current Cuban scene, in which tourism “is poised to explode.”

According to the experts, no sector of the Cuban economy seems more ready to “unlock future economic expansion and generate the foreign exchange necessary to release Cuba from the hard-currency tourniquet that has throttled growth. Eventually, agriculture and industry could take off, but not before government economic policies are thoroughly overhauled, and that will take time. Other promising sectors, such as biotechnology and the creative industries, are launching from much smaller bases. Only tourism has such a firm foundation from which to expand, and enjoys such favorable market conditions.”

There’s always a before and an after

The report proposes an overhauling of the Cuban government policies on tourism since the triumph of the Revolution on January 1, 1959 until the present. “We find that the Cuban leadership has had a historically ambivalent approach to the industry, turning to it only with reluctance in times of crisis. Consequently, Cuban tourism has lost market share and forfeited potentially valuable foreign exchange earnings. Today, the government is seeking to correct those policies and has ambitious plans for dramatically expanding tourism capacity.”

The authors describe a Cuba in which tourism was always linked to the United States. In 1930 the island received 80,000 tourists, 85 percent of them from the United States. By 1957 the amount of visitors from that country stood at 272,000, and they came fundamentally for the casinos after a law in the United States hoped to put an end to gambling.

“In offshore Cuba, large hotel-based casinos and nightclubs were owned or operated by well-known criminals, including Lucky Luciano, Santo Trafficante, and Myer Lansky, in some cases necessarily in partnership with the Cuban strongman and president, Fulgencio Batista. To many excluded Cubans, and to a revolution with deep roots in both Jesuit morality and Communist austerity, these luxury hotel-casinos symbolized all that was decadent and wrong under Batista’s bloody rule.”

This construction in the imagination of the revolutionary Cuba would explain why this sector barely grew in several decades. However, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the contraction of the Cuban GDP by 30 percent, forced the island to turn to tourism and later to remittances. “During the decade of the 1990s, the Cuban government invested an estimated $3.5 billion in developing the tourism sector. To provide badly needed investment capital and to ensure a steady flow of tourists, Cuba welcomed European hotel chains to partner with newly created Cuban state-owned tourism groups.”

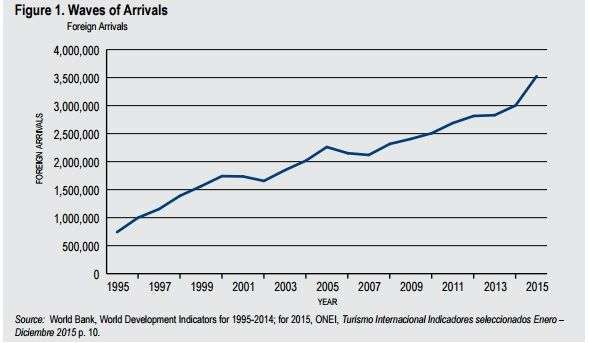

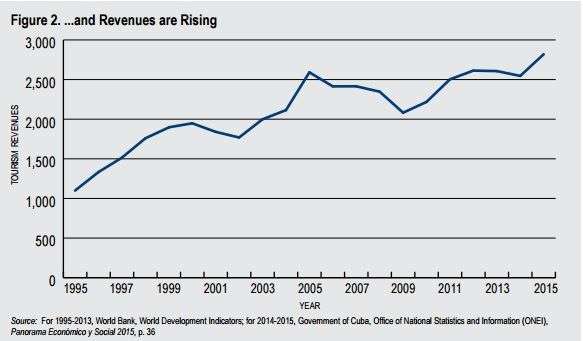

That’s how foreign firms like Meliá and Iberostar entered the incipient Cuban market, with an emphasis on sun and beach tourism, and installations located in zones faraway from urban centers. “Tourist arrivals rose from very low levels in the post-revolution period to 740,000 by 1995—triple the flow that had characterized the 1950s. By 2000, new visitors had reached 1.7 million, and tourism receipts hit $2 billion.”

Feinberg and Newfarmer say that by the mid-2000s, earnings growth from the tourism industry had begun to slow due to several factors, that is: the impact of meteorological phenomena (hurricanes), world recession (2008-2009) and restrictions for foreign investment, which explains why after peaking in 2005 at over $2.6 billion, tourism receipts hovered in the $2 to 2.6 billion range, before surging to $2.8 billion in 2015.

The structure and the future

The research of the hundred-year-old Washington D.C.-based Brookings Institute delves in analyzing the current structure of the tourism sector in Cuba, in which the state is the dominant actor “in the sector as owner of main services, regulator of resource flows, and recipient of investible funds and general revenue. However, in recent years, the non-state sector has grown through the proliferation of restaurants (paladares), private room rental (casas particulares), and self-employment (trabajadores cuentapropistas) serving the industry, such as private construction companies and taxi drivers.”

In addition to the contributions in systematization and analysis of dispersed data on a sector run by several ministries on the island and a growing participation of private enterprise, the study by Feinberg and Newfarmer stops to determine how much tourism contributes to the national GDP (2.5 percent) and to compare it to that of nearby countries. In this sense, Costa Rica (4.8 percent) and Dominican Republic (5 percent), for example, double that contribution. Such a state of things has to do with the type of management of the hotel installations, in the first place, but also with the imports, reinvestment, monetary and exchange rate policy, and the hiring systems.

“To meet the government’s stated objectives of tripling tourism revenues by 2030, the government has adopted the goal of adding some 108,000 rooms to the existing hotel stock of 50,000 rooms of three-star quality or better using Cuban standards. This would accommodate as many as 10 million visitors (not including cruise ship tourists). To accomplish this ambitious real estate investment goal, we calculate Cuba will require roughly a total of $33 billion in new investment over the 15 years to 2030—a massive sum in comparison to the overall size of the Cuban economy or its current investment rates.”

The strategy for the expansion of the tourism sector in Cuba lies in the capacities of the state enterprises that will build close to 70 percent of the rooms planned without the participation of foreign capital, and they will have the majority of the ownership over around 30 percent of the joint ventures.

“This strategy of relying on retained earnings may make sense from the perspective of the sectorial conglomerates, but…it seems unlikely that sufficient financing and domestic savings would be available to reach Cuba’s ambitious goals.”

Instead of seeking to finance almost all the planned investments in hotels through domestic cash flow, the country could mobilize more foreign savings welcoming more foreign investment. For the hotel sector and the industry in general (like golf and other leisure activities), this requires establishing more transparent regulations to attract foreign investment and rationalize the excessively prolonged approval processes that have delayed many long-gestation projects.

Conclusions for the two shores

In the opinion of the experts, “Cuba has laid the foundations for potentially rapid growth of the tourism sector. The country has abundant tourist attractions, undeveloped natural resources, and a welcoming culture that make it a jewel in the Caribbean Greater Antilles.”

However, the island will have to adjust its financing scheme and consequently review some of the bureaucratic procedures to approve foreign investment projects if it wants to experience a takeoff in its smokeless industry.

In that sense, Feinberg and Newfarmer recommend encouraging private investment in B&B services. Simplifying the tax structure facing private enterprises and property owners would create incentives for saving and investment. Modifying the tax system for the payroll and the regulations would encourage new jobs, would not discourage them as they do now.

Other keys to success, according to the analysts, point to the resolution of the dual currency/dual exchange rate system, the fiscal policies, the increase in productivity and a change of strategy toward increasing quality and increasing the domestic value added. Cuba hopes to concentrate on more exclusive markets, which supposes investing in better quality services and installations and in more staff training. Instead of concentrating so strongly on large tourist complexes, “it might do better to dot the island with smaller, more customized destinations. Smaller establishments can offer an eco-friendly and authentic experience.”

Lastly, they give high priority to the increase in connectivity. “Cuba has already taken steps to better connect the Cuban economy to the rest of the world through its incipient efforts to expand internet, telephone services, and air connections. Yet the internet is central to the development of the tourist industry. Consumers—both for business and leisure travel—increasingly look for connectivity as a condition of a quality vacation.”

Nevertheless, the report’s contribution goes beyond scrutinizing the current Cuban scenario and making recommendations for possible Cuban interlocutors. It also offers a critical route for the U.S. government, with the elimination of the blockade/embargo as one of the fundamental cores of its policies toward the island, in addition to the investment of U.S. capital and facilitating the alliances between environmental NGOs and Cuban counterparts.

Ever since the November elections in the United States, some have argued that Cuba’s opening should be reversed. In the tourism sector this would be counterproductive for the interests of the United States for three reasons:

– the Cuban Americans and other U.S. citizens that meet certain carefully outlined requirements to visit Cuba are speeding up the development of private and family businesses;

– some have argued that all visitors’ spending mainly benefit the Cuban military, but actually the majority of the rooms are not managed by the Ministry of the Armed Forces;

– the imposition of restrictions on U.S. visitors or private commerce can reduce tourism incomes – at the expense of damaging the Cubans -, but will have a limited impact on the course of the industry’s expansion because the Europeans, Latin Americans and others will continue strengthening their commitment to the Cuban economy.