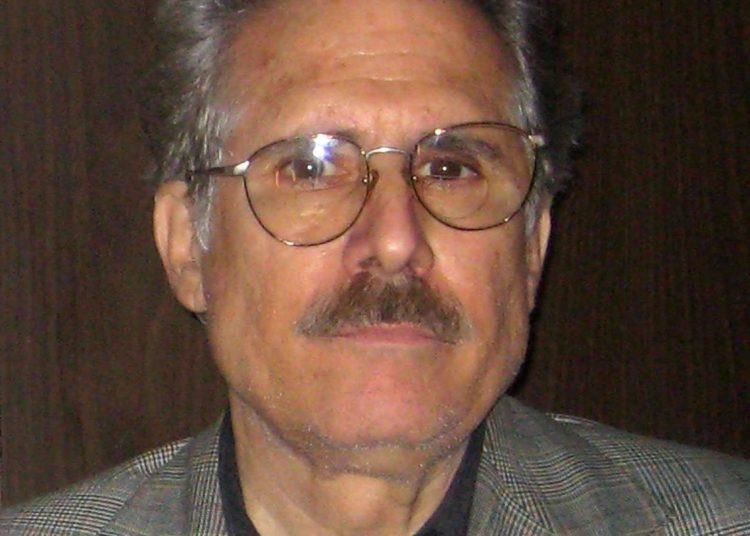

Cuban human rights activist and the last survivor of one of the first political crises of the Cuban Revolution, Ricardo Bofill Pagés, died in the early hours of Friday in Miami after a long heart ailment and from complications in an operation on his back, several of his friends confirmed to OnCuba. He was 76 years old.

Bofill was one of the pioneers of the controversial movement for the defense of human rights in Cuba. The creation, by him, of the Cuban Human Rights Committee in 1976 was a sort of watershed in the third decade of the Cuban revolutionary process.

One of the tasks he focused on was the preparation of detailed reports on human rights violations that managed to attract the attention of organizations such as Amnesty International or the UN Human Rights Committee.

After leaving prison in 1974 he also headed the birth of Cuban dissidence in terms similar to that which arose in the late Soviet Union at that time. It is curious because Bofill’s first imprisonment occurred in 1968, when he was accused of being more pro-Soviet than pro-Castro during the episode of the so-called “microfraction.”

The microfraction

This process is a controversial episode of the Cuban Revolution and one of its first political crises. It involved a group of members of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP), known as “the old communists” from before the Revolution confronting the new ones, formed by the Revolution. The Cuban leader, Fidel Castro, accused them of conspiring with Moscow.

The case begins in mid-1966 when Fidel Castro found out that Aníbal Escalante Dellundé, an old communist activist who never hid his devotion to the Soviets, who became the main leader of the PSP before 1959 and who had an outstanding influence in power during the early years of the Revolution, was holding clandestine meetings with old PSP members, including Bofill.

The objective, according to the island’s authorities, would be to establish an opinion movement within Cuban political circles, based on the fact that despite maintaining good relations with the Soviet political leaders of that time, Fidel Castro was not really sufficiently pro-Soviet and, therefore, not trustworthy.

There were two strong arguments at that time: that the main leaders of the Revolution had petite-bourgeois ancestry and did not want to take into account the supposed revolutionary leadership of Moscow at a global level.

For almost a year they were left to their antics until the investigators put a report on Fidel Castro’s table: Escalante and other old activists had been organizing conspiracy meetings and establishing contacts with diplomats and journalists from the Soviet Union.

In short, the group wanted Moscow to find out that, in the opinion of the group, the leadership of revolutionary Cuba had all the conditions to turn its back on Moscow. One of those indications was the annoyance Fidel Castro manifested when Moscow secretly negotiated with Washington the withdrawal of nuclear missiles from the island in October 1962, a crisis that brought the world to the brink of an atomic conflict.

Raúl speaks

To put the emergence of a divisional group within the Communist Party of Cuba into context, on January 24, 1968 the now first secretary of the party, General Raúl Castro, presented a report to the Central Committee with details of the conspiracy.

“In mid-1966 we received diverse information on opinions, criticisms of the Revolution’s leadership and specifically of comrade Commander Fidel Castro, as well as comments against the ideological line of the Party, from some old members of the PSP. Up to now the information had arisen spontaneously, many of them referring to statements made at the end of 1965 in the Dos Hermanos estate, which was managed by Aníbal Escalante Dellundé, where festive meals were held with the participation of old members of the PSP, friends of the latter,” said Raúl Castro, at the time minister of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR) and second secretary of the PCC.

The microfraction was never very extensive. Its members identified by the authorities did not reach four dozen and not all were sanctioned. But among them “political statements were made such as that Aníbal Escalante represented the true ideological current of the working class. That his mere presence in Cuba, even if he did not participate in political activities, represented an obstacle for the petite-bourgeois elements entrenched in the country’s leadership, that there is a policy to eliminate the old communists, that this policy began with the events March 1962,” said the former minister of the FAR.

Raúl Castro referred to Fidel Castro’s row with Escalante, which according to Fuentes put an end to the presence of the former leader of the PSP in the sphere of power, in particular by stopping the almost total control of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI), which preceded the formation of the PCC.

When at the beginning of 1962 Moscow consulted with Havana on the installation of nuclear missiles on the island, Fuentes explains, “Fidel finds himself in the need to reinforce his control over the ORI and for that he takes Aníbal out of the party. [At that time] the people of the PSP [who no longer existed legally] were totally in power,” he emphasized.

The issue is that he established the condition that negotiations be made directly with him without going through Escalante. “You could not install the missiles with Aníbal in power,” adds the writer living in Miami. For the next four years the old PSP activist worked on the writing of the Moscow weekly magazine Tiempos Nuevos.

In his report, Raúl Castro adds that the group “spoke of a strong anti-Soviet current” and, in addition, they emphasized that “the USSR is the country that should lead the global hegemony.” They also “argued that the petite bourgeoisie was the predominant current in the politics of the Revolution and that attempts had been made to pass all power into its hands.”

In this sense, said Raúl Castro, they maintained that “the petite bourgeoisie and the right-wing elements were preparing the conditions for the events of March 26, 1962 [when Escalante was removed from the sphere of power] and the October Crisis, they made it possible for the trade policy to be reconsidered, projecting once again towards the capitalist countries, the very petite bourgeoisie’s purpose was not only to move trade towards the capitalist areas but to move Cuba back to the system that had been swept away in January 1959.”

That is, the Escalante group considered the revolutionary leadership, the leaders of the July 26 Movement, as bourgeois elements with plans to leave the Moscow orbit and return to the arms of Washington. Hence the interest in contacting the Soviet leadership, through its diplomats and journalists in Cuba, in order to convince it to put pressure on Havana in the economic sphere to correct the island’s “adventurous” positions.

But there is more. They were also very critical in their assessments of the armed struggle to seize power, a political thesis rejected by the Soviets and embraced by the revolutionary leadership that came down from the Sierra Maestra. An example of this is the foundation in 1966 of the Tricontinental.

The sanctions

That meeting of the Central Committee lasted almost 24 hours, partly because Fidel Castro spoke twelve of these hours, a speech that was never published. Also addressing the meeting was Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, who was a very important member of the PSP leadership, the only leader of the organization that joined Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra and at that time the government’s number three man. In addition, Fidel Castro read a letter of self-criticism by Escalante, which was not given great value, and the explanations of the only two members of the PCC, José Matar and Ramón Calcines, were heard, after which they were expelled from the political organization.

The others involved, who had already been detained during the meeting, a total of 35, were tried in the following months and received jail sentences of between 15 (Escalante, the most) and two years.

The old leader of the PSP was not long behind bars. He was released in 1971, shortly before Fidel Castro’s trip to Chile, following a request from the Chilean Communists. Escalante died in 1977 while managing an agricultural farm.

A couple of months after the Central Committee meeting, Fidel Castro launched on the steps of the University of Havana the so-called Revolutionary Offensive, which ended private property. In that speech, before going into the subject he referred to the microfraction and announced that more details would not be disclosed other than those published in the press, admitting that doing so could have diplomatic implications, obviously referring to Moscow.

“Unfortunately, all problems cannot be dealt with publicly. We are a constituted State, and as a constituted State we logically have to abide by certain norms, and in the complex and difficult world we live in, not each and every problem can always be discussed in public…. Simply because there are questions of a diplomatic nature, issues that have to do with relations between states, and things like that, or issues that could be harmful because they are known to the enemy,” explained the former Cuban president.

But he opened a small window and made an assessment of the impact of the past crisis: “It is true that some of the political manifestations of the microfraction elements and the microfraction phenomenon could have been dealt with more widely―and we dealt with that aspect extensively in the meeting of the Central Committee―, it must be said that the microfraction as a political force―as a political force―lacked significance; as political intention, its actions were of a serious nature; and as a current within the revolutionary movement, a frankly reformist, reactionary and conservative current, although we understand perfectly well that in the atmosphere of these times many currents of that nature circulate,” said Castro.

And he closed the matter with a “after all, we consider that the microfraction is an already resolved problem.”

Since then until our days, the process of Aníbal Escalante and his 34 colleagues has not been declassified. 51 years have passed. The protagonists have died. The Soviet Union no longer exists.

From Marxism to dissidence

Ricardo Bofill ended up sentenced to twelve years in prison for being a part of the microfraction. When they arrested him, the police only found a study on the Cuban political-economic situation at that time that was to be sent to Moscow. He served eight years. But he had a hard time finding work. He was barely able to get small jobs as a librarian, although before the microfraction he was a professor of Marxist Philosophy at the University of Havana.

Disillusioned with Cuban government policy, he began to dedicate himself to the defense of human rights. In 1976, after leaving prison, he created the Cuban Human Rights Committee, an initiative that in a way made him return to his pro-Soviet roots. He designed the group and its work of denunciations to the image of what the Russian dissidents did at that time: press conferences, press releases for the international press and preparing reports addressed to international organizations. He could do no more. He sought political asylum at the French embassy in Havana, during the 1980s, and returned to prison briefly, accused of “enemy propaganda.” He left Cuba in 1988.

“He was fundamental, essential, in the creation of the dissidence. He is the father of all that. He had the help of Elizardo Sánchez Santacruz and Adolfo Rivero Caro [a former political commissar of the Revolution] who also helped him later in Miami to derail the dissident movement, because he turned it into a movement of Miami’s extreme right,” writer Norberto Fuentes explained to OnCuba.

When Fidel Castro died in 2016, the activist, already ill, told television in Miami that he was not “happy” about the demise. He was the last survivor of the microfraction group.