For a week now, Havana has been living its “new normal.” After being the epicenter of COVID-19 in Cuba for months, and experiencing an outbreak in August and September that forced the imposition of harsh restrictions, the Cuban capital began October with a de-escalation that seeks, according to its government, “to reactivate production and services,” and thus boost the economy, mired in the quagmire of the pandemic.

When reporting on this change on September 30, the Havana authorities affirmed that the measures applied until that moment―among them, a night curfew and a substantial limitation of the socioeconomic life of the city―had had a “positive impact” and that the statistics on the disease in Havana―new cases, active cases, deaths, and open transmission events in recent weeks―showed “a trend towards epidemiological stability.”

However, they explained that the risk in the capital was still high, so the reopening would be partial. For this reason, along with the lifting of prohibitions and the reactivation of a group of activities, several restrictive measures would remain in force―such as the prohibition of interprovincial transportation to and from Havana―and mandatory sanitary provisions, both for people and private businesses, state enterprises and institutions. In addition, the high fines applied to those who violate these measures would be maintained, one of the aspects that has caused the most controversy during confinement.

Several days later, there seems to be a majority popular acceptance of the de-escalation. The streets are bustling with life―although, to be fair, there was never a lack of daily traffic of people and the lines grew to monumental dimensions; buses, private taxis and other means of public transportation are again circulating; people have returned to beaches, parks, and family outings; more restaurants, cafes and other services have reopened or are preparing to do so; children and young people break the confinement of recent months; and schools begin to prepare for the restart of classes.

However, although the “easing” of the restrictions was longed for by many, its announcement did not cease to surprise and worry a part of the population, which has seen the city go from a considerable closure―at least, in theory―to a broad reopening, in which self-responsibility has gained greater prominence both in practice and in government discourse.

“I am worried that there will be another outbreak,” Elisa, who this weekend went out with her husband and son to “take a walk” through the city after weeks without being able to do so, said to OnCuba. “We decided to go out because the truth is that we needed it, and because it is not known how long this can last,” she explained. “The previous time, when we entered phase 1, after a month we had to go back, because the cases started to increase again and the city became more complicated, even more than before, and now the same could happen. How can people be controlled after so long?”

“I understand the government because we couldn’t continue as we were,” says Juan Carlos, Elisa’s husband. “No country in the world has spent the entire pandemic locked up, not even the wealthiest. There’s no economy that can stand that, and it also goes for people. The thing is that Cubans, and especially Havanans, are not easy. If even in the midst of the restrictions there were those who continued to have parties, made lines at dawn, and thousands of fines were imposed, I believe that now it could be more difficult to control the situation if the government and the police don’t follow up on the people.”

“Well, I didn’t expect that much,” admits Rosa, a retired teacher on her way to her usual purchases in her area of the Cerro municipality, “but I’m still happy because I’ll be able to see my grandchildren again after all this time. Imagine what joy. I also thought that they would only remove the measures they put in place in September, but if they opened more it’s because the government believes it’s possible now. In addition, people have to understand that they have to do their part and the doctors and the authorities aren’t the only ones that must do their part. In the end, what is at stake is our own health and that of our family.”

Normality with mask and limited autochthonous transmission

The idea of a “new normal” caused by COVID-19, which involves forced coexistence with the disease and the use of masks and other sanitary regulations to control its spread, is not, in reality, new. It has been handled by experts and international authorities almost since the beginning of the pandemic, when it was understood that the battle against the disease would last months or perhaps years, and that even with effective treatments and even with a vaccine that manages to generate immunity, the coronavirus had arrived to disrupt the daily life and perspectives of the entire planet. At least for a long time.

The possibility of waves of COVID-19 that would alternate with periods of control, of cyclical closings and reopenings in which the restrictions would be extreme or relaxed according to the prevailing epidemiological situation, did not take long to be demonstrated in practice. This has happened in many countries and also in Cuba. After a first peak in April and a progressive decrease in cases in the following months, the island had to face―and still faces―an outbreak since the end of July that first expanded in the western part of the country and now has the central region as its most complicated scenario. And in it, Havana has been the undisputed protagonist.

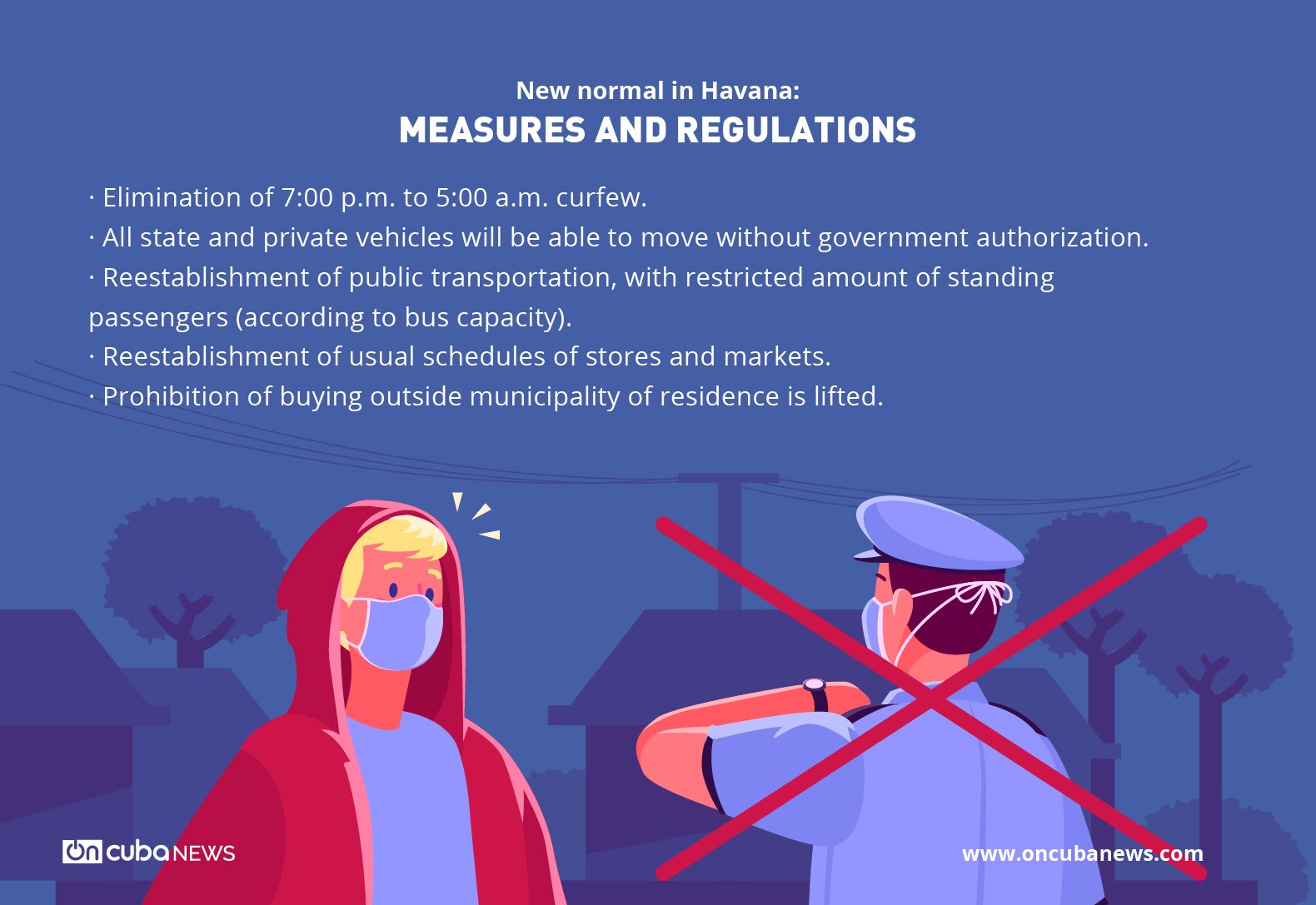

This motivated that, after reversing the de-escalation in the capital, just a little more than a month after its start, the authorities tightened the screws even more given the growing spread of the coronavirus throughout Havana, and maintained throughout September the strictest measures of all that have been applied in the city of Havana during the pandemic. Among them, a greater restriction of the mobility of vehicles and people, the prohibition of movement at night, the limitation of purchases only in the municipality of residence of the people, the closure of productive activities and non-essential services, and a reinforcement of health surveillance.

However, 30 days later and in view of the improvement in the epidemiological panorama―according to official indicators―not only were the last measures dismantled, but other restrictions until then in force in the city were relaxed, while some regulations were included that had been initially established for the post-COVID-19 stage, according to the plan presented by the Cuban government in June, when it was decided to start the reopening in most of the provinces.

This, despite the fact that even today, when the new daily cases have dropped―this Wednesday, for example, Havana reported only one―and the “new normal” is becoming an everyday thing for Havanans, the city has not returned to the recovery phase―as it did in early July, after the rest of the country―, but remains in the limited autochthonous transmission stage, the name given by the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) to the stage in which the epidemic spreads in a territory within certain margins and control protocols.

This was clarified by the Havana authorities themselves after announcing the current measures and the prohibitions lifted in the capital, and was explained to OnCuba by Dr. Francisco Durán, National Director of Epidemiology of the MINSAP, in a recent press conference on the situation of the epidemic on the island.

“The capital remains in the phase of limited autochthonous transmission,” confirmed Dr. Durán when answering a question from our media, “only with the relaxation of some restrictions that correspond to this phase, such as with regard to the restart of urban transportation with various requirements, to the reopening of the beaches, swimming pools and a group of services with limited capacity, and in which social distancing, the use of disinfectant solutions and the mask, among other measures, are guaranteed.”

An unprecedented scenario

Along with the elimination of the curfew, the reopening of the beaches and the resumption of public transportation, the scope of the reopening now established in Havana even includes the restart of the school year―already underway in most Cuban provinces—, starting next November 2, a step that was not planned in the government plan for the post-COVID stage until phase 2 of the de-escalation. Also the start of services in restaurants and cafeterias at 50% of their capacity, originally intended for phase 1; and the gradual reopening of movie houses, theaters, amusement parks and shopping centers closed since the beginning of the epidemic.

However, gyms, bars, discos and other nightspots remain closed; also transportation to and from Havana, except for exceptional and officially authorized cases; the screening and verification of authorizations at the entry and exit points of the city. Similarly, the imposition of high fines―of 2,000 and 3,000 Cuban pesos (CUP)―to those who violate the provisions and the mandatory nature of a set of sanitary regulations, which include the use of the mask and maintaining physical distance in public spaces, as well as hygienic measures and temperature control in work, social and educational centers.

It’s a symptomatic and not inconsiderable variation of the hitherto strict methodology designed and followed by the Cuban authorities for each of the phases of the epidemic; of an unprecedented scenario on the island―in which the transmission of the coronavirus coexists with measures initially designed for different moments of confrontation and recovery from the disease―, the result of reality that, after seven exhausting months, has forced the government to appeal to pragmatism and citizen responsibility.

Consequently, the preventive and welfare approach―and also the discourse―promoted in the first stage of COVID-19 on the island has been modified, and the notion of a “new normal” has been assumed in which, without neglecting the prevention and control of the disease, one must learn to coexist with it and in which, according to Dr. Durán after the question from OnCuba, “the measures will be adapted in line with the epidemiological situation.”

“It’s true that there are people who fear that these measures may cause a reappearance, an increase in cases that could cause a setback, but this is systematically evaluated, in the provinces and nationally, and the measures are being adapted,” acknowledged the national director of Epidemiology of the MINSAP. “It’s not that we are going to sacrifice our health for an economic problem, but we have already spent seven months in which activities have been totally restricted, and people also feel it and we have to recover.”

“So what are we going to expect next year, when a vaccine can be had, to restore normal life?” Durán wondered.

This question, as was said by a Cuban health authority―someone who, moreover, has earned the respect of Cubans in recent months and has become a kind of voice of conscience about COVID-19 in the country―evidences the change of perspective that operates today, from the official level, but also in daily reality, in the understanding of the pandemic. As the government itself has reiterated, the “new normal” is undoubtedly here to stay and entails new requirements and challenges, both in Cuba and, particularly, in Havana.

But, how much has the economic background influenced this change in perspective? How has the disease evolved in the Cuban capital in recent months, just when it has gone from de-escalation to closure and now back to reopening? Have these changes and the measures that accompany them been as consistent with what the statistics show? We will approach this in a second part of this work.