The environment, natural or built, is there, but the landscape does not exist without a gaze. It is a cultural product, it is history’s imprint on geography, it is the space that contains time. The landscape is a selection, a perspective, it is a point of view, it is a construction of the gaze. Before the same panorama there are as many landscapes as observers. And in the same way that the landscape is modeled and composed, the eye is educated and cultivated.

The landscape is a complex gaze, not just visual. It is also auditory (the Cuban scene is always accompanied by a powerful soundtrack), olfactory (certain images can evoke stenches or suggest perfumes), even thermal or tactile…and, no doubt, emotional. The landscape is also made up of symbols: the buildings, vehicles, people suggest or send messages (we do it even when creating our own personal landscape, the way we dress, our hairstyle, etc.). No landscape is mute.

Gaze is culture

There is no neutral gaze. The gaze tows and carries a culture, a history, a context. It is difficult for a rural eye to distinguish architectural styles, for an urban eye to identify tree species. The European is no longer surprised and is delighted like the Cuban in the face of intense urban lighting. The Cuban is not astonished and enjoys as the European the absence of publicity in the urban landscape.

Gazes have diverse scopes, even physical ones. There are gazes limited to the neighborhood, others that do not go beyond housing. It may be the old man’s gaze, that of the housewife, that of the child. Their only exit to the world is sometimes limited to the television screen. This constitutes their referent and shapes or deforms their gaze. It is convenient to teach and learn to gaze differently, understand the eyes of others, learn to see things with other eyes. But you don’t just have to gaze at the landscape. We must also open the landscape to the eye, we must tear down the walls that today do not let us see, for example, the Havana bay, open the spaces and public buildings, bring down walls, obstacles, fences, prohibitions….

Unfortunately, material poverty impoverishes the eyes. In some parts of the city there is no choice but to get used to filth, noise, ugliness…and with it, the ability to perceive harmonies, contrasts, rhythms, colors, textures, proportions is mutilated or limited…. Living in society doesn’t have to mean living in filth. Only a mutilated, empty, blind eye is capable of destroying the sidewalks of La Rampa.

In fact, by building and rectifying the city, shaping the landscape, we build ourselves. It is us and our landscape.

Challenges of the Cuban gaze

Gazing is a challenge. To gaze is to choose, declare and decide and this is not simple nor can it be naive.

How to harmonize unity and diversity? On the road to equity, in Cuba, we stumble upon homogeneity and fall into monotony, into the typical project. Undoubtedly, the centralization of decisions and projects has some responsibility. The process of economic and social adjustment that we are now going through is diversifying the subjects of change in the city and this undoubtedly brings greater diversity. But up to where? How to harmonize this multiplicity and disparity of decisions and particular interventions in the collective sphere of the city? What should be regulated and what not in the remodeling of the urban space and landscape?

How to combine socialization and privatization? It is clear that the city is a fabric of public and private spaces, but what are their respective limits? What spaces can be privatized and which not? We must redefine what is legitimate and what is not in citizen coexistence. Why is it not considered legitimate for neighbors to invade through the door the physical space of my house and it is admitted that they enter through the window, flooding my auditory space with their music or noise?

How to reconcile modernity and tradition? We know that the country will face important transformations in the coming years. In that context, what deserves to be respected or restored and what doesn’t? What is the landscape that is considered heritage? It is not as obvious as it seems. Years ago the industrial landscape was something that had to be erased; now it has been incorporated as a very important urban heritage. How to insert the new architecture in the existing city? What is legitimate to demolish and what should be reused and reestablished? We have already dismantled jewels such as Varadero’s International Hotel or the Pedro Borrás Hospital in Havana…. What will be next?

How to combine the global with the local? Should we see globalization as an aggression against identity? What is that identity, the one we build for tourism? What is genuinely Cuban? What is the identity of Cuban architecture? The combination of the portal, the patio, the high ceiling and the blinds? “Knowing how to play hide and seek with the sun,” as Carpentier wrote?

How to gaze without having answers to so many questions? To think, argue and declare oneself on these issues is to educate the eye. To build and rebuild the landscape in which we live is to model and compose, day by day, in the debate, that multiple and changing gaze, leaving our mark on the city.

The Havanan gaze

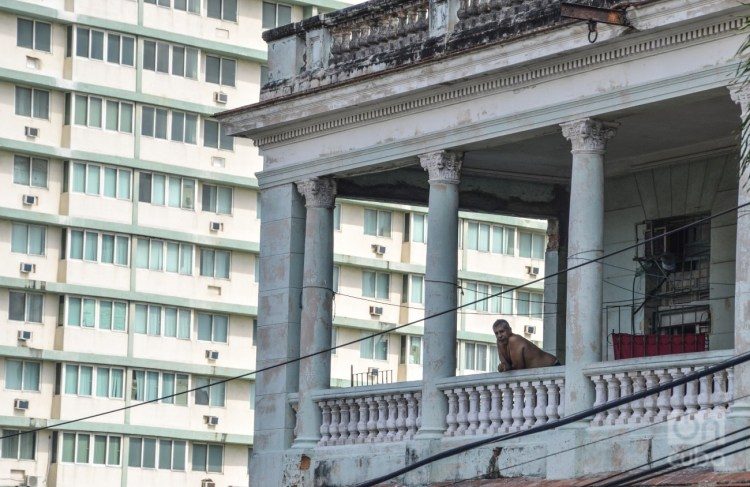

That battered landscape that we all enjoy and suffer today is undoubtedly the result of 30 years of postponements and 30 more of crises. It is important to take into account that half of Havanans have lived their conscious lives in a “special period,” that is, their dominant citizen landscape―with exceptions such as that of old Havana―has been that of the gradual, progressive and overwhelming impoverishment of their city.

The impact of that crisis has been multiple. In demographic terms, Havana is a city that has been losing population for years, is aging rapidly and is becoming rural in its habits. In economic terms, its progressive deindustrialization stands out, as well as the privatization of the management or the cooperativization of small state facilities together with private initiatives. Socially, the increasing reduction of social spending accelerates a worrying stratification and inequality, favoring individual or family life strategies over the social project.

In physical terms, the degradation of the infrastructure, the growing vulnerability in the face of meteorological phenomena, the scarce and poor aesthetic references in the new works and adaptations together with the weak urban control and no advice, have generated a strong visual and landscape degradation, to the paradoxical extreme that the most injured and rickety areas have become a tourist attraction.

It is the landscape of dirty realism, dotted now with some interesting works by those who can afford (and risk) hiring an architect or a designer, or invaded by the disturbing and growing “disoriented architecture” mentioned by Eusebio Leal, of those who build as they can.

Reversing this degradation means rescuing the city. This means, in the first place, to claim its values―as a powerful concentration of economic, cultural, heritage resources, etc.―not seeing it as a problem but as a solution (as Lerner said). It will be necessary to strengthen its government with capacities and resources so that it can effectively manage its plan (which one?) and its investment budget. It will be necessary to link planning and management to not act aimlessly, facing only one emergency after another, endlessly “putting out fires.” To achieve this, it will be necessary to democratize urban management through the increase of public information and popular control.

An increase in the resources dedicated to the city is indispensable. All available sources should be used: premises, using better the little or badly used buildings, strengthening the public-private partnership, strengthening and expanding the territorial fiscal instruments; national sources, given that the city is contributing much more to the national budget than it receives from it; the international ones, although for this it is necessary to strengthen the legal and financial instruments to avoid speculative processes. It will be necessary to favor the construction of an intense associative social fabric, promoting as much as possible the participation of young people. It will be necessary to gaze at the city inwards, identifying and using the areas of opportunity (Havana bay, the west coast, Ciudad Libertad, and all urban gaps), rescue and integrate the southern territory, and also gaze outwards, preparing for the inevitable opening of the city to the growing international flows of people, merchandise, finances and information.

Along with this, it is essential to educate and train the eye on cultural actions. We will have to relearn to play with the urban landscape, discovering it and enjoying it as the Havana population has been doing massively on the occasion of the last Biennials.

Artists, architects, designers have a fundamental social responsibility, as well as the social media. We must dignify degraded landscapes such as Alamar, Centro Habana, the peripheries…, “monumentalizing” and building attractive public spaces in these areas. We must open the landscape of the bay to Havanans, open to the public exceptional works such as the Art Schools, we must recover the vision of the coastal facade from the sea, identify and condition all urban lookout points, unveil the city.

And not only must we show the present, but, more importantly, the future: we must publicize everything that is dreamed, planned, imagined, projected, as well as what is done to dignify Havana. We must reconquer the hope for the future, without forgetting that to the extent that we destroy the landscape, the landscape will destroy us….

Приветсвую, скажите пожалуйста как Вы сделали такой вид новостей? Или это так и было уже в готовом виде шаблона?