In September 2019, OnCuba published an editorial on five steps that would foster better relations between the nation and emigration: allow political participation and vote of Cubans living abroad, simplify bureaucratic procedures and the costs of obtaining and renewing the Cuban passport, eliminate the requirement of returning to the island every two years to maintain residence, homogenize the migratory categories with the aim of offering equal treatment and promoting capital investment through incentives and guarantees. [1]

Undoubtedly, the implementation of the previous consular, political and legal proposals would greatly contribute to overcoming the severe restrictions of the past and to renovating the space between the nation and emigration. If, according to the most recent statistics provided by the Cuban State, there are a total of 1,485,618 Cuban citizens residing abroad, not counting their descendants, it is evident that these steps are logical and reasonable. [2] The figure represents about 13 percent of the current population.

Moreover, if the 2017 census of the United States reflects a total of 2.3 million Cubans, including their descendants, in this country where most of the emigrants reside, who, in addition, mostly support relations with Cuba and whose remittances have become one of the mainstays of the Cuban economy, the suggested steps are also both fair and necessary. [3] Let us remember that Miami, where almost a million and a half of the emigrants reside, is the city with the largest number of Cubans after Havana.

However, the laws approved or to be approved and the attitudes, prejudices and states of mind that underlie those laws do not always coincide. Despite the formal measures taken in favor of normalization, much remains to be achieved in the ways of thinking the emigration and the emigrant. Obviously, the nation has grown and we are all Cubans, but if we scratch the surface, the island’s imaginary still perceives Cubans who left as different: consumed by nostalgia and unable to reach fulfillment far from their roots.

Why is it that a film like Regreso a Ítaca (2014), with a script by Leonardo Padura and Laurent Cantet, underlines the figurative castration of the character who returns after sixteen years of absence? This pathetic character has repeatedly tried to write a novel in exile, but fails again and again. By “losing” the homeland, he lost his raison d’etre. Why does a work of fiction like La novela de mi vida (2002), by Padura himself, introduce us to the exiled professional as a creature obsessed with the past despite the two decades since he left Cuba?

A third example is Miel para Oshún (2001), by Humberto Solás, whose young protagonist, at the climax of the film, confesses he is overwhelmed by his cultural duality, product of his residence in the United States. The drama of Alberto Pedro, Weekend en Bahía (1987), and the segment entitled “Laura,” by Ana Rodríguez, in Mujer transparente (1990) reproduce similar situations. Is hybridity really a source of confusion? Isn’t Cuban culture syncretic, par excellence?

Some stories suggest other schemes, but those already mentioned support a certain naturalized imaginary that devalues emigrants even in spite of their utilitarian enjoyment. They rely on discourses that in turn derive legitimacy from the projected images, feeding each other. The representation of emigrants falls within the semantic field of the subtraction: they are fragmented, diminished, frustrated, dispossessed and incomplete beings.

A turn of thought is necessary. In part, the fallacy stems from the ideas that continue circulating about national identity. Thinking in terms of roots, trunks and branches, as is common, implies a hierarchy that enthrones the first two undermining the last, the weakest and most vulnerable. Already well into the new millennium, it is worth reflecting on the speeches at hand to think the nation, taking into account the role that emigration has assumed among Cubans throughout history and, above all, today.

We have the prime example of José Martí, who lived most of his adult life in New York. Martí did not cease to be Cuban because he had come to closely know the United States, a country that aroused in him criticism and admiration in notable chronicles such as “The Brooklyn Bridge” and “Coney Island.” Shortly before, Félix Varela would have recognized the role that New York played in the Cuban imagination of the first half of the 19th century by choosing to remain in that metropolis.

In more recent times, Lourdes Casal is not only the author of the poem “Para Ana Veltfort,” in which she confesses, without a hint of drama, her simultaneous marginality and belonging to two homelands while wandering around the West Side of Manhattan, but also of the article “Reflections on the Conference on Women and Development,” which goes beyond the Cuban theme. However, her remains rest in the Pantheon of Emigrated Revolutionaries in Colón Cemetery.

Martí, Varela and Casal were not paralyzed by longing. They never lost their ability to produce or seduce by their example. Unlike the shipwreck scene fabricated by the movies, exile sometimes acts more as a meaning to life, and not everything in it is sorrow. Although pierced with nostalgia, the self-referential film “A media voz” (2019), by Patricia Pérez and Heidi Hassan, constitutes irrefutable proof that the filmmakers have overcome the implacable wistfulness by reaffirming their work as filmmakers.

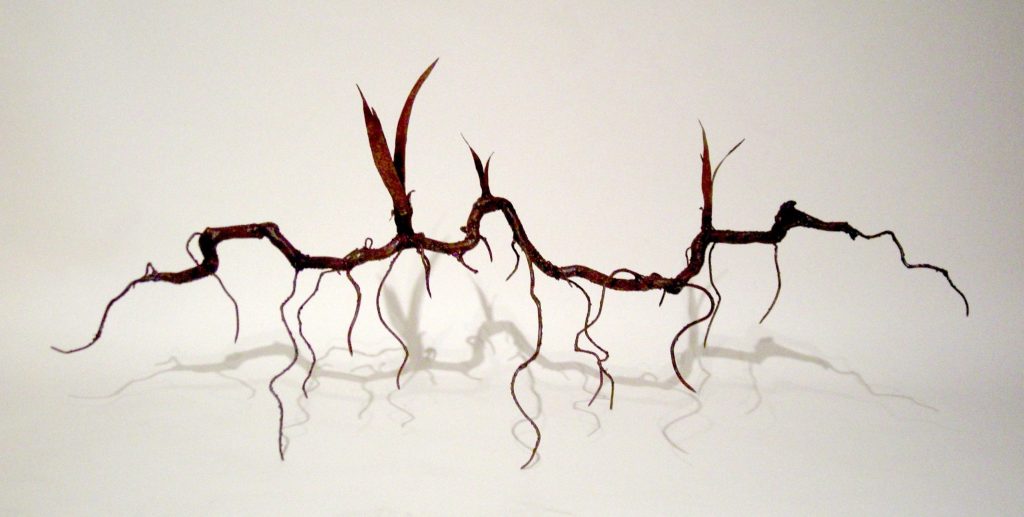

Given our history and the growing importance of emigration, we should consider a non-arborescent, but rhizomatic, model that would help refresh the Cuban imaginary about identity, making room for more opportune images. Such a model is not unprecedented; other critics have made comparable proposals in order to expand them. Coming from botany, the rhizome, with horizontal and underground roots such as those of lilies, serves as the basis for the concept developed by philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari as an alternative to the arborescent figuration of knowledge, which denotes verticality and fixity.

The rhizome, being more diffuse and extended, supposes horizontality, decentralization and mobility, generating correspondence between all kinds of elements that compose it. It results in distant outbreaks (Cubans scattered throughout the world), but linked together (by common interests: for the good of all). Needless to point out the democratic spirit, not hierarchical, inherent in the term. The rhizome as a foundation would modify the rules of the game.

The very laws approved by Cuba justify the paradigm shift. The 2013 immigration reform has made possible the fluidity of current emigration and the option of repatriation. According to official figures, there have been a total of 57,746 repatriation applications since January 2013, of which more than 60 percent come from the United States. We must not jump to the conclusion that these involve permanent returns. In a recent sample of 19 returnees, whom the author interviewed, the repatriation involves, in the majority of cases, not a definitive return to the place of origin, but a license to enter and leave, to maintain, if you want, the best of the two worlds. The returnees also take advantage of the ups and downs.

To this is added the coordinates that govern the exchange with the diaspora, which several scholars have delineated with respect to multiple fields, such as mutual influence in popular culture, virtual collaboration in the areas of technology and even finance, and the exchange of audiovisual media. [4] The exchange continues even when there are barriers to physical movement.

But even if we stick only to travel, the entry of Cubans residing abroad, especially from the United States, has experienced an increase, even in the face of the drop in tourism. Official statistics show a total of more than 4.6 million trips by 1.1 million Cuban nationals in the last seven years. In 2019 alone, 623,831 Cubans living abroad returned to visit, a number that represents an increase of 3.9 percent over the previous year. [5] According to some reports, among these there are those who travel to celebrate quince parties, to spend vacations with their family or to take school uniforms manufactured in South Florida. The space between the nation and emigration has long since diminished.

The fluidity found in each of these manifestations is different from the image of the only, odd root. It is not that the roots have lost their meaning, but rather to adapt them to the forcefulness of a more mobile and plural world. A rhizomatic relationship between the nation and emigration would engender an equitable and inclusive origin thanks to which the Cubans of the diaspora don’t lose their rights as citizen or their ability to lead a dignified life anywhere in the world and that it be represented as such in the stories about emigration.

Such stories should neither delimit the terrain of the Cuban nor lower those who work it outside of Cuba. A genuine change in the symbolic order, as laborious as the most, together with specific measures that make interaction possible, must be part of the pressing search to normalize, institutionalize and narrate the relationship. A task for everyone, the renewal of the discourse is correlatively essential.

Notes:

[1] “Cinco pasos que el gobierno cubano puede dar para acercarse a la emigración,” September 29, 2019, visited on February 9, 2020.

[2] López Blanch, Hedelberto. “El proceso de normalización con la emigración es continuo, irreversible y permanente.” Juventud Rebelde, January 14, 2020. Visited on February 9, 2020. The figures related to the repatriation requests that appear below also come from this article.

[3] Facts on Hispanics of Cuban origin in the United States, 2017, September 16, 2019. Visited on March 1, 2020.

[4] See the works of Albert S. Laguna, Denise Delgado Vázquez, Lisa Maya Knauer, Jorge Duany and Susan E. Eckstein, who, among others, have addressed these issues.

[5] EFE. “Más de 620,000 emigrantes cubanos regresaron de visita a la isla en 2019.” El Nuevo Herald. January 7, 2020. Visited on March 1, 2020.