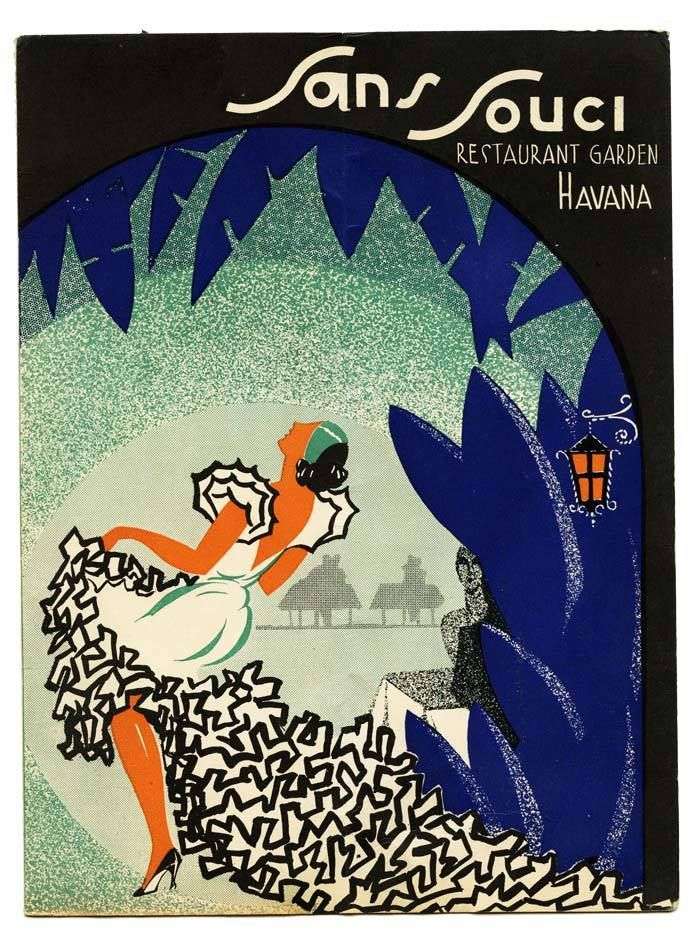

In the mid-1950s Tropicana Cabaret was big, but the Sans Souci was at the height of its takeoff, competing with the cabaret in Marianao in splendor and cosmopolitanism. It was going through a process of changes and remodeling that had begun in 1955 and was concluded a while later at an approximate cost of a million dollars.

The management of Norman “Roughneck” Rothman, a mafioso married to Cuban star Olga Chaviano – the star of the cabaret between 1953 and 1955 – had given way to that of William G. Buschoff, better known as Lefty Clark, from Miami Beach, and one of the men of Santo Trafficante, who a report by the Department of the Treasury written in Havana considered a suspect in drug trafficking, like his boss.

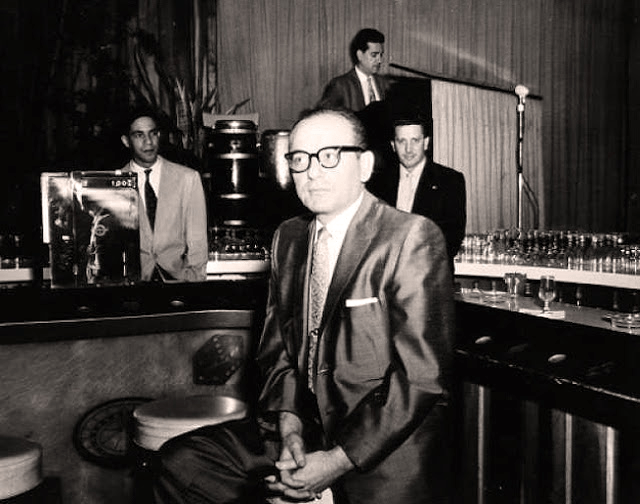

Santo Trafficante in Sans Souci’s bar.

There was a reason for the remodeling and investments: one of the principal problems of the casino in the Sans Souci (Carretera Arroyo Arenas) was related to the unfair gambling practices, leading to complaints and denunciations in the U.S. embassy as well as the press of that country and the Cuban Tourism Commission, presided over by Marcial Facio. Especially the rip-offs associated to the razzle-dazzle dice game in which clients always came out the losers – and in a bad way – had entered a crisis. This game, incorporated by the Sans Souci casino in 1952, had been extended to other Havana gambling houses because of the absolute money it left to the bank.

The problem became complicated because one of its victims, attorney Dan Smith, from Pasadena, California, fell into the trap and signed a check to Sans Souci for 4,000 dollars to cover his debt, but he cancelled it when he returned to the United States, which Rothman contested in court. But bad luck at time rears its head: the point is that Smith had political connections with Vice President Richard Nixon (1953-1961) ever since he had been the Republican senator for the state of California.

According to diverse sources, Facio had Fred Freer, a gambling expert, come from the United States to resolve the problem, but the move was not successful: the man had to go in hiding due to the pressure of the created interests; finally, he was able to leave the country and the official – an already retired sugar baron, a friend of Batista and Meyer Lansky’s boss in that institution – had to resign to his post.

The government had no choice but to react in the face of the event due to a combination of factors that included the U.S. pressures and the plans to continue expanding the hotel and tourism investments, a priced source of income and cuts for that corrupt elite. According to the magazine Vanity Fair, Smith’s complaint to Nixon gave rise to a chain of telephone calls to the Department of State, the Embassy in Cuba and the Cuban Tourism Commission. When Batista got wind of it, he rapidly acted. A short note published in The New York Times on March 31, 1953 announced the expulsion of 13 Americans who were employees of the Sans Souci and Tropicana nightclubs.

Batista ended up by sending the army to the casinos, which is underlined in a feature article of the Times as well as an article about the Sans Souci by Jay Mallin, a journalist specializing in Cuba who began his passion by writing about Havana’s nighttime and mad life for magazines like Cabaret.

To clean that image and underline its international class, the cabaret’s new strategy had two tracks: the first consisted in taking to Cuba U.S. singers, actors, dancers and models, as well as renowned European figures. A very interesting list that included Denise Darcel and Edith Piaff – both hired for the inaugural show -, Cab Calloway – who in 1949 had already played in one of Meyer Lansky’s dominions, the Montmartre –, Ilona Massey, Dorothy Dandridge, Tony Bennett, Marlene Dietrich, Sara Vaughan, June Christy, Johnny Matis, Dorothy Lamour, Maurice Chevalier, Billy Daniels, Nat King Cole, Eartha Kitt, Tony Martin, Ginny Simms, Connee Boswell, and Vicente Escudero, among others, in addition to hiring Cuban musicians in the Nevada Cocktail Room like César Portillo de la Luz and Frank Domínguez. In 1957 the magazine Cabaret commented that for the first time a series of well-known stars had been taken to Cuba by a single nightclub and that since the opening of the Sans Souci…it has had more attractions than all of Havana’s nightclubs during the last five years.

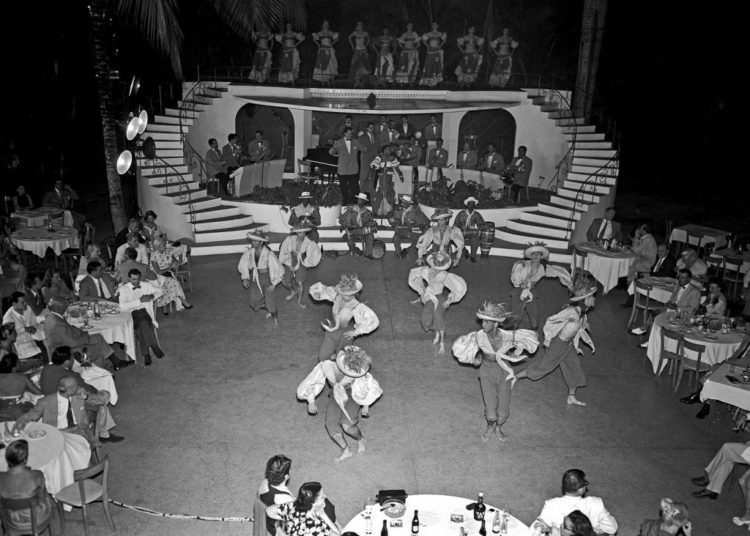

The second one, the splendor of its shows and productions. According to the aforementioned publication, the mayor part of that millions of dollars’ worth of investment had been for the entertainment business. “Sun Sun Babaé” (1951-1952), the show by Roderico “Rodney” Neyra conceived based on Afro-Cuban roots and with the star performances by Merceditas Valdés and Celia Cruz, was followed by a more fabulous production along the same line: “Bamba Iroko Bamba,” by Alberto Alonso, who replaced Rodney when the latter was hired by Tropicana. The show involved around 100 participants at an estimated cost of some $25,000 a week. It was “the biggest and most expensive show ever put on in Cuba,” according to director Alberto Alonso, a student of Nicolas Yavorsky, former dancer of the New York Ballet Theatre and, in short, one of the founders of Cuban ballet.

Productions of this type, in the Sans Souci as well as in Tropicana, were a time of splendor for those shows, which gave jobs to Cuban choreographers, dancers and musicians, and contributed to a great extent to their international prestige. And with legendary models, veritable “flesh and blood goddesses” – like in the title of a famous Tropicana show – providing that the ebony be excluded from the equation: only white or mulatto women, Mulatas de Fuego type.

But the Sans Souci or the Tropicana can’t only be reduced to casinos and the U.S. mafia. It was a time in which Cuban culture was decked out with those shows, absolutely competitive in the international sphere.

I am curious, what became of the Sans Souci after the Revolution? What is it now? Thanks.