Whether you put one name, the other or both…Google is going to flood your screen with texts and images that bring these beings together, that speak of shared illusions, common experiences, joint projects and that show two very close people, one always more smiling and outgoing than the other, although that other reveals joy through his puppets.

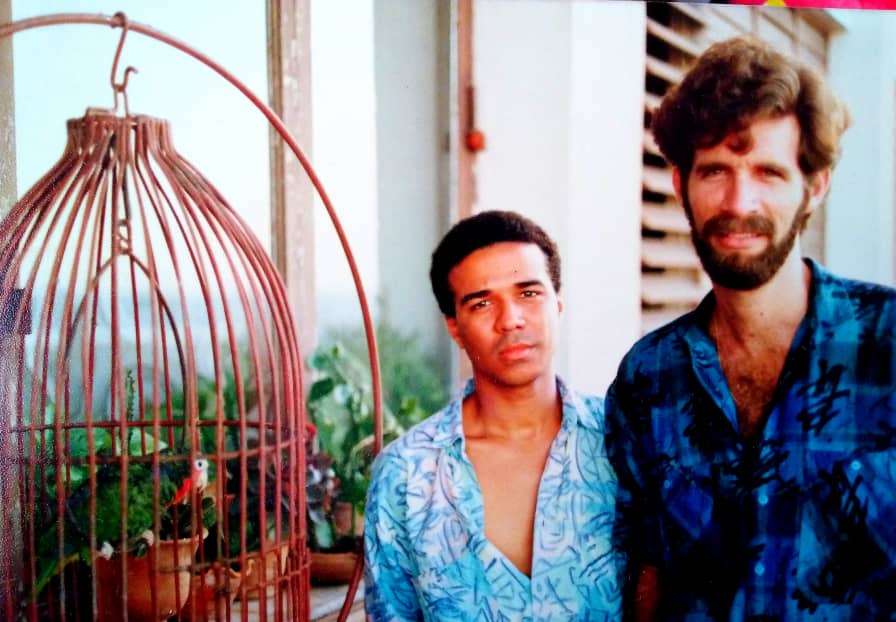

Rubén Darío Salazar and Zenén Calero have been a couple, in art and in love, for more than 30 years. And that union was already known in the Cuban artistic media long before Google and other Internet search engines existed.

The trackers of admirable couples, and they sure exist — and also the homophobic ones —, could easily find them since the late 1980s on the streets of the city of Matanzas. Zenén was since 1979 the theater designer of the Papalote group, one of the most prestigious Cuban theater companies for children. There, in 1987, the young actor Rubén Darío arrived. They met in the commotion of the stages, the lights, and the puppets.

It is Rubén who affirms that as a child Zenén played at being what he is today, a designer. And indeed “under my bed I would make the stages and put the lights that I took from the Christmas trees; with that I created shows and I imagined even the movements,” says the designer.

“I continued doing that job, but with an impasse, because I didn’t know that it could be a profession. I was a country boy or rather a beach boy. I lived in Boca de Camarioca. First I went through mechanical engineering, then I was a Spanish and Literature teacher, until the theater appeared and everything else was left behind, because theater design is a career that takes over life.”

“He was a sea boy and I was an urban boy,” Rubén had it clearer from very early on because, as he likes to say, he practically grew up in the Santiago de Cuba Guiñol theater. His mother was a worker at the Santiago headquarters of the Cuban Institute of Radio and TV and the Culture trade union and it was practical for her child to be cared for inside the theater, while she carried out her work. “Later with my neighbors I would put on puppet shows, I would dress them with my mother’s and father’s clothes, or with whatever I found, and I would write the texts. So I also directed as a child, and that continued in primary and secondary school.”

The journalism career that Rubén Darío Salazar began at age 18 was quickly replaced by the possibility of restarting his university studies at the Higher Institute of Art, from where he graduated from the same course as two other giants of Cuban acting: Broselianda Hernández and Osvaldo Doimeadiós.

He then arrived in Matanzas on a recommendation from narrator Mayra Navarro. “She told me: ‘If you want to do good puppet theater, you have to go to Matanzas.’ She said it because of Papalote, the group that Maestro René Fernández directed and that he still directs. And I didn’t think twice. Matanzas has a connection with the people of Santiago, Heredia lived there, for example. And when I arrived, Zenén was already there making his designs: an intelligent, intrepid boy, a lover of the profession. And I was also pure passion with the theater and with puppets.”

After working and learning for years with René Fernández, an experience that they take as a privilege, in 1994, in the midst of the Rafters Crisis, Rubén and Zenén had the idea of creating a new group. It was on one of the most critical days of that summer, at the conclusion of a show at the Sauto Theater that they had put on precisely to distract the children who every day saw entire families leave the Matanzas coast, at times in rudimentary rafts, in pursuit of reaching the United States.

“Teatro de las Estaciones is the vibration of the love and respect given to Cuban culture, to Dora Alonso, from Matanzas, to Martí, from all over Cuba and the world, to Lorca, who is one of our authors, to Norge Espinosa, who is a contemporary. In our Company we have found the vibrations we need to live,” Rubén Darío affirms.

La niña que riega la albahaca, Pelusín y los pájaros, La caja de los juguetes, La virgencita de bronce, Federico de noche, Alicia en busca del conejo blanco, Por el monte Carulé…are some of the pieces directed by Rubén Darío with the stage, costume and lighting design by Zenén Calero, who is also the creator of hundreds of puppets that have come to life on stage and on other media such as audiovisual, and more recently with the incursion into the wonderful technique of stop motion. The puppets created by Zenén have come to crowd their storage spaces, but when they least imagine it they leave their corner and come back to life.

The option of moving to the Cuban capital or emigrating to another country has never been in the plans of this couple, which has not lacked offers for a change of this magnitude. Practical and sentimental motivations have sustained their staying in the so-called City of Bridges, a few kilometers from Varadero, one of the most famous beach resorts in the world.

“We have created a world based on our artistic interest and we have had a lot of support from the Matanzas government,” says Zenén, who from the 1990s until today has grown his previously narrow workshop and puppet house, which used to be reached by a narrow staircase. “Today we have a space that is the Pelusín del Monte Cultural Center that I direct and that houses the Teatro de las Estaciones company, directed by Rubén, and where I have used the teachings of René Fernández, not only artistic direction, but of the general direction of an institution. I feel like I do things that I saw him do. And in that space we have the possibility to do everything.”

“If there’s something that unites Zenén and me in addition to the passion for theater and life, it is love for this country. Cuba is not a perfect country, none are, but it is our country. We have had the privilege of having been to the greatest festivals in the world: in New York, in Charleville-Mezières, in Toulouse, in Genoa. And in the end Zenén and I look at each other and one says: what’s the matter? And the other: I have a desire to go to Cuba now…. That cannot be explained, that is not told, one has that feeling or not.”

In August 2021, the program Vivir del Cuento, one of the most popular and one of the few critical of Cuban social and economic reality on TV, brought to the screen an edition titled Titiriteros. The performance of Rubén Darío Salazar and the puppets created by Zenén Calero plus an incisive script added spice to the much-liked television show. Critic Norge Espinosa wrote about this in Cubaescena: “The traditional laughter, with overtones of social satire, which has characterized the space, was combined with the puppets that reproduced the main characters of the space so that the presence of the animated figure was not a footnote or a passing addition. Through those doubles, glove puppets, a criticism seeped of that type of civil servant who distrusts art as a recourse to remove stagnant ideas, and who sees in humor a mirror that only reveals his own suspicions.”

Rubén assures that if something has happened to them, it is that they have never been prejudiced with anything, neither in life nor in art and that is why they have worked with artists from opera, popular music, cinema or television. However, prejudices have beset them, to a greater or lesser extent.

Ever since you have been a couple, have you felt rejection or social pressure in Cuba because of your sexual preferences or your relationship?

Rubén Darío Salazar: Nothing is so new new, nor so old old. Prejudices, that attitude of confusion, blindness, hallucination towards what is not the norm, ends up putting those singled out on guard or simply in the position of enjoying the suffering of the other because there is no guilt other than being consistent with feelings, which do not know gender, or any of those absurd definitions with which many humans go through life cataloging what they know or think they know and what they do not know. At the age of 25, the personality is already formed. I met Zenén in the middle of a theater company. Seeing us together was normal, so I never felt any rejection. The occasional suspicious look that never took my sleep away, but nothing else, that’s the truth.

Zenén Calero Medina: Rubén was in his twenties and was, is, very charismatic, like I was introverted at thirty-something. Neither he nor I like the unnecessary affectation because we have never gone through life trying to attack anyone with what we feel, rather we have shared that love with friends, colleagues, family… people without prejudice, who look us in the eye, not at the crotch, which is otherwise a very personal place. Some people in my family did look at us badly, adding to that racial prejudice, that backwardness. Others did not. We have always been respectful with others, with ourselves. We have many things in common, the main one: having a frank behavior with everyone. We have nothing to hide, we have a lot to give.

How did you cope with sexual discrimination in childhood and adolescence?

Rubén Darío Salazar: I was an artist since I was a child, and although that is a condition that does not define you sexually, because being sensitive is something that is for everyone, being an artist is always suspicious with respect to males, as strong trades have been suspicious for females and that doesn’t mean anything either. It is hard for a child to be singled out or criticized. Now they call it bullying, but abuse, offense, humiliation for those who have challenged traditional male roles have always existed. My mother has always supported me in all my decisions, which made me grow up with a well-placed self-esteem. She always demanded that I be polite, get good grades, read to be smart. It is not that mothers are blind, but they really observe their children with their soul and expect from them much more than the dispositions to live, armed in other centuries. I continued being an artist in adolescence, and that is a very rebellious age when it is perceived that it is unfair to be looked down upon for liking poetry, painting, music, literature or ballet. I never looked down at any suggestion of offense. It must be that since I was born in the neighborhood of Los Hoyos, in Santiago de Cuba, and I come from a brave family, I don’t have much to do with fear, although I have always been short.

Zenén Calero Medina: My family was very sexist. I was a different child and adolescent. I always tried to be accepted by my cousins and friends, by my family in general. Something in me was not like in other children. I liked animals, that they not be mistreated, I liked painting, music, period movies. I created my world and it was never the same as anyone else’s. I felt a lot of pain at that stage of my life. It is very hard to be censored in childhood and adolescence. Somehow I was a victim in the 1970s of the parameterization, because at the age of 15 I was expelled from the Matanzas Provincial School of Art, without ever telling my mother the true reasons. It was difficult for me to understand this, as I was one of the best students in the fine arts specialty. Some years later, teachers of that time, watching me grow up and become a creator, apologized to me. That did not cure me of so much pain and injustice, but it made me see that some humans have shame on their faces and that is an honest, dignified condition, because anyone can be wrong, it is life that has no turning back.

How would you educate the new generations not only in tolerance but in respect, acceptance and natural coexistence with differences in sexual identities, preferences or practices?

Rubén Darío Salazar: The task that arises is great, there are many years of mistrust, of terror of what is different. That fear regresses, hides. There are too many people masked and frustrated by prejudice, if not accusing, implacable, radical towards the issue of sexuality. Children are not born with prejudices, it is the adults who educate that soul in hatred, in scorn, in abuse with the weakest or the different. Do not cry, do not speak with a fine voice, do not gesticulate, it is all a decalogue to be a man and to be a woman, not to be human beings. There are parents who prefer delinquent children to homosexual ones. And that’s where a path begins where there is hardly any space to dialogue, accept, which is different from tolerating or understanding. There is a lot of work ahead and we cannot leave the specialists or those responsible for educating alone in that. The family and the government also have their work there. You cannot build a country by hiding identities to be accepted or functioning with the morality of the Middle Ages when women were close to the witches and artists to the devil. Life has shown that this is a fallacy, a way of discriminating and cutting off the soul from the brain. Too many twisted and unhappy people already exist on earth.

Zenén Calero Medina: I work with a lot of young people and I think they are less prejudiced than the adults. Sometimes so much pressure on them has made them break the rules and go to the other extreme and that is also dangerous, because being ultra-modern as many want to be, has a price. Better to dialogue with them. It is what I do, try to show them how beautiful life is, that there is a lot of beauty to enjoy. Some listen to me and others do not, and they lose themselves in apathy, addiction or the most useless and superficial vanity. I trust young people, I like them and at the same time I try to make them better people, better creators, better children, sons and daughters, parents…the matter is difficult, but I always bet on optimism. In that, Rubén and I are similar, although I seem more melancholic, he is really melancholic with a carapace of well-made props.

What message do you have for Cubans at this time of debate about the urgent need for a new Family Code?

Rubén Darío Salazar: 35 years with Zenén has made me a better person and a better artist, I have not needed a family code that includes equal marriage and other rights to reach this conclusion. But the existence of a law that protects that right is an exercise in civilization, equality and respect for love.

Zenén Calero Medina: Perhaps this legal provision, the changes that are being pursued in the new Family Code, has surprised us when we are a little older. Perhaps the majority does not approve of it, that is not going to put an end to my feelings, which cannot be regulated. Perhaps yes, and we will have an inclusive country, at the height of human development and on the side of justice.

Rubén and Zenén carry their desires and dreams wherever they go, be it inside or outside of Cuba. “And with our children, the puppets,” they add. Many years ago in Sweden, where equal marriage was already possible, someone said to them: “Why don’t you get married here?” And with the same speed that characterizes Rubén Darío when he speaks, like someone who is always in a hurry, he says when telling it as he probably said it at that time: “No, I want to get married in Cuba, when the family code that concerns me exists, when minds open up and realize that love is above all.” Zenén, next to him, nods with his good man’s smile.

In 2020, Rubén Darío Salazar and Zenén Calero received the National Theater Award. The jury, made up of National Award winners Carlos Pérez Peña, Gerardo Fulleda León, Verónica Lynn and Carlos Díaz, and designer and teacher Nieves Laferté, recognized that this “pair of stage creators has contributed to the theater for children and puppets appreciable values in Cuba regarding their artistic, investigative and teaching work.”

A few months earlier they had taken on the challenge of reviving, almost from ruins, the room of the Guiñol Nacional de Cuba puppet theater. Rubén was appointed as general director of that essential Havana theater space and Zenén is there, by him, redesigning and giving color and light to the site so that it stops being the dark and silent basement it has become in recent years and returns to be filled with puppets and joy.