Riddled with small ID cards. That’s the face of the inside of the door of the Casa del Migrante Nazareth, a shelter belonging to the Catholic Church in Nuevo Laredo. José Perez: Coyote. Juan Fernández: use of the cell phone. Miguel López: refused to wash up…photo, name, surname and reason why each guy who knocks should not be let in. The rules of the house are very strict.

One of the latest regulations incorporated is that each migrant hand over his/her cell phone when entering: it will be given back when they leave. The priests who are at the head of the Casa adopted that measure after “The Zetas” – as the transnational mafia born in that same province is known – started to kidnap illegal immigrants using, it is believed, the complicity of someone staying in the Casa del Migrante.

The Casa Nazareth, headed by Father Marcos, mainly shelters Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Mexicans who were deported by the United States and, now, Cubans.

***

Ofelia (32) and David (33) have been in the Casa for some weeks, they resolved to leave Guatemala when a gang from El Progreso, their city of birth to the north of the country, threatened to kill them. They reported it to the police, not because they had any hope of justice but rather to have some legal proof of their persecution.

They emigrated with their three children: David (14), Berzalli (12) and Brandon (4). They crossed to Mexico and in Tapachula they met with hundreds of Cubans doing the paperwork for “safe-conducts,” the temporary visa for 20 days that Cubans need to reach the north and cross with dry feet. They thought it was a good idea to follow them.

When they arrived in Nuevo Laredo they tried to cross, but were deported to Mexico. Ofelia and David decided that, although they did not pass to the north, their older children would do it. So they gave them all the papers, crying, they kissed them goodbye and made them cross the Rio Grande through the international Bridge.

– David and Berzalli would have been accepted, they are in a U.S. immigration office waiting for one of our acquaintances to go pick them up, we will pay them with work the day we are able to cross because we will cross no matter what, commented Ofelia to OnCuba while she breastfed Brandon.

The child is crazy about a Honduran girl eight years older than him; he spends all his time running around the shelter.

Brandon (4) and his Honduran friend (12). Photo: Irina Dambrauskas.

When Ofelia and David bumped into the Cubans in Tapachula they also found out about the commentaries made about them by the other Latin American migrants:

– They envied them because Cubans have the privilege to cross and we don’t, but it’s because they don’t know them. We got to know them and they’re good people, Ofelia says.

***

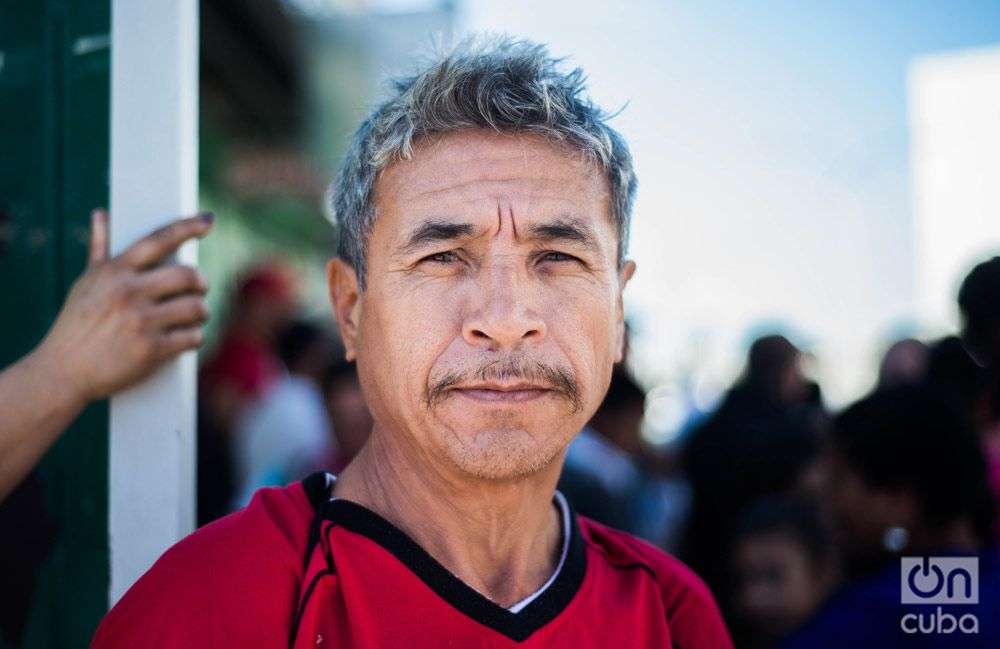

Marcos (44) was a corporal in the Salvadoran army. At 41, he says, he refused to obey an order to torture. Then they tortured him. He escaped and went upwards, as people escape in Central America, and ended up in the funnel where Donald Trump wants to build a wall.

Marcos comes from El Salvador where the violent scheme to which the criminal gangs and the State belong every year rank the country among the first places in the world in terms of homicides.

Marcos arrived in Nuevo Laredo because he didn’t have another alternative. If Trump builds a wall…:

– Getting into the United States was always a latent possibility, if things are made more difficult for us I don’t know what we’ll do.

He in the Casa getting ready to swim across the Rio Grande, despite the Zetas and the U.S. border patrol.

For the time being the Cubans coincide about one thing: they are not willing to do such a thing.

***

Standing on the corner of bridge 1, Milton comes to a conclusion:

– Thanks to that wave of Cubans we are eating pretty well.

Many Nuevo Laredo neighbors come close during the day to give them food. The migrants waiting on Bridge 1 receive, thanks to Mexican solidarity, four meals a day.

Milton went up to Mexico from Honduras in 2002. He established himself in Jalisco and had a son. One day he got on La Bestia and went in search of a future for his son in some place in Texas. La Bestia is what they call the freight train that immigrants climb on camouflaged in Mexico to cross the country from one end to the other to get close to the United States.

In 2013 Milton was caught illegal in Houston, Texas, and was deported:

– Now with Trump they’ll go hunting much more, he reflects, while he tries the taco the volunteers of the Casa del Migrante offer him.

He returned to Mexico where the Zetas extorted money from him. News from his family arrives: in Jalisco there are increasingly more problems to feed his son so he will again get on La Bestia, now the other way round, and at the end of a few days of travel they will again meet.

***

Before, when there were “wet feet / dry feet,” many Cubans only stopped at some hotel, despite the journey they arrived with some money left from the rest to pay for it. In recent weeks they have started to divide among the few shelters Laredo offers, but they decided to concentrate themselves in the AMAR shelter, run by local Pastor Aaron Méndez.

The last to find out was Lázaro, a psychologist from the University of Matanzas who ended up alone in the Casa del Migrante Nazareth.

Lázaro is out of place in the canteen: wearing an ironed blue shirt and pleated pants, he looks like the director of the Casa and not an illegal migrant.

– I sold my little house in Matanzas; I bought a tour of Italy and asked for a temporary Schengen visa [the European Union’s visa] for the trip. But I wasn’t going to go on the trip; I did that because Mexico lets in for 180 days all those with a Schengen visa, he explains to OnCuba.

Lázaro has a prosthetic left leg. It was impossible to cross 10 borders and at least a jungle as an illegal migrant. He had to seek a shorter route.

All his belongings boil down to a small bag with a toothbrush, shampoo, a t-shirt and a coat. No more.

Lázaro could have studied a career that in the country he expected to reach costs thousands of dollars, but he argued: “In Cuba education is free, but they mortgage your freedom. How many times have we paid for our studies with the low wages we get?” He says he suffered because he criticized the government in a course he was giving, that in Cuba being critical leads “to your life being made difficult by them” and that one day he said to those who harassed him: “These hands are for working not for destroying.” But it didn’t matter, he was punished, they started marginalizing him from any interesting and profitable projects.

He says this with anger, furious, far from the Hondurans, Salvadorans and Guatemalans to whom those problems seem light.

Lázaro has a supreme reason for being in Nuevo Laredo, that’s why he isn’t going to Europe even though he has the visa and he continues in Mexico: he is going in search of his wife, a doctor who is in Miami who has been waiting for him for a year. He tells the story and starts crying.

– One year of separation! That’s what hurts me the most; and if we start some paperwork now it would be at least four years…. I almost don’t have enough money left, that’s why I have to come here, he says broken up, before asking for a car that will take him to some other shelter where he is not the only Cuban.

He was taken to the AMAR shelter, where almost all those from his country are staying: “The first thing I will do when I get there is shower, what’s most important is to not let yourself go.”

“If you don’t cross, I’ll cross and if it’s necessary we’ll cross the Atlantic together,” he has promised his wife.

– We don’t want much: being together and living well working in what we know, he says.

Father Marcos lends him the phone. He has been thinking; he looks at the corner where the flags of the Latin American countries from where migrants have come to the Casa and he says:

– Cuba’s flag has to be added.