For several months I haven’t heard anything about my uncle P’s life in San Francisco, no matter how hard I try to contact him on messenger, I don’t get a response. I especially insisted on December, the month of his birthday, Christmas, New Year’s Eve. I also insist when my grandmother bombards me with questions about her son as if I lived in his own neighborhood. Sometimes I think my grandmother cherishes the idea that, for some esoteric-diasporic reason, her grandson and her son are far from her but somewhere close enough to protect each other, while she, the matriarch of the family can’t take care of us.

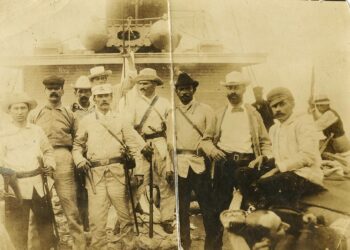

My uncle was the first in the family to leave Cuba, strictly speaking, he initially did not leave Cuba, because he arrived at the Guantánamo naval base on a battered raft and stayed there for several months. Later we learned that he was in a military base in Panama until he continued on his way and one day he sent photos already in the Yuma. The family received with sadness and concern the news that he had left the country by sea, at the same time I know that a breath of hope animated our souls in that hot summer of 1994.

The first time I heard about the Yuma was through my uncle A, who had delusions about living in Havana and hopefully making the leap to the United States from there. Since I was little I was worried about that term, “Yuma,” then I discovered through the same family stories that the inspiration came from some cousins from the island’s eastern region who had come left as “scum” in the 1980s. I knew about all that because I spent a good part of my vacations accompanying my uncles to look for avocados, guavas and akee to sell in the neighborhood; making sweets on the patio of my grandmother’s house, or changing from Palmolive soap to a car battery for rice in Sancti Spíritus

My grandmother cried a lot and inconsolably when she found out that her son had left, to this day she does not get over it, no matter how many times we made her believe that it was for the good of the family. Even when we bought her first Panda TV with money sent by her son, her sadness and disappointment did not leave her, it was as if she had lost a part of her own body. One day, the whole family met at the house of a neighbor who had a video cassette player, something rare at that time, and with joy we saw for the first time a recording of my uncle in his daily routine, in his new home, in his new land, the land of dreams. Happy, smiling, well-fed, well-dressed, and dancing euphorically to Willy Chirino’s “Ya viene llegando,” which gave us immense peace of mind, and at the same time the feeling that finally, someone in the family would be in a different economic status to that already reproduced by several generations.

Money, gifts, aid began to arrive quickly, which were rigorously administered by my uncle P, so that all his brothers, sisters, nephews, friends, relatives felt protected, sheltered, in the midst of the multiple shortages that Cuba was experiencing during the special period. My uncle A was especially happy, if his brother continued to be successful, he would get his residence, perhaps American citizenship and in a short time he could claim him. I had my first good watch, and the first perfume to make me feel less shy when coming face to face with a girl. But, as the Cuban saying goes, happiness in a poor man’s house is short-lived.

A year after my uncle left Cuba, his 26-year-old brother fell ill with cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma shattered his youth, his dreams, and ultimately his life. The relationship between them was deep, and I remember that in the midst of the illness it became more present, it was as if they wanted to shorten the distance and the pain of perhaps having to give up the idea of not seeing each other anymore. At the Oncological Hospital my uncle proudly and without prejudice wore his sports suit with the American flag, and during visiting hours we listened together to the Salsa cassette on Calle 8 on the Sony recorder, both things present that had come from the Yuma, sent with affection by his dear brother.

My uncle P almost desperately tried to come through humanitarian means to see his brother who was getting worse, the political bids between governments began and everything was delayed. My uncle A died crying out in agony to see his brother for the last time…his brother back in the Yuma, I think he was never the same again after that irreparable loss. The irreparable distances, the dreams severed like a flower on a stem, the life that continues impetuous, intense, conflictive and does not listen to excuses, nor to a soul in mourning.

My uncle’s successive disappearances began shortly after, he began to distance himself from everything and everyone. According to urban legends, he could be in jail, in the process of being repatriated for some serious infraction or living the sweet life and drinking the Coca-Cola of oblivion. It has been 27 years and my uncle did not return to Cuba, nor did he manage to become the Messiah, the savior of the family’s poverty. The penultimate time we didn’t hear from him for almost ten years, during which the most dissimilar stories were speculated, for my grandmother it is the conviction that her son will one day appear and surprise us.

The harsh truth is that my uncle, for many reasons, did not achieve the American golden dream. For a long time he was imprisoned, he is prevented from obtaining U.S. citizenship and leaving the territory, he has had to rehabilitate several times due to chemical dependency and lives on the streets of San Francisco in a modest tent, although in stages social services supports him with food and accommodation. One day when we talked, he told me: Boy, take care of yourself, if you are going to leave Cuba, sometimes things are not as one imagines them! I thought about him a lot, and I also understood his words better, when I watched the moving documentary Lead me home, released on the Netflix platform in November 2021.

I am not particularly pleased to talk about my homeless uncle, nor do I dislike him nor am I going to evade his reality, which is also mine, that of our family and that of many other families in the United States, in Brazil, in Cuba, in the world. As I write these lines I think of the impiety, the distances, the challenges, the heavy burdens that are placed on the backs of people who emigrate. Nobody expects failure, least of all the emigrants themselves, we all expect success, especially economic success, as a tangible result of the fact that one’s life changed and one was part of the change of others.

At the beginning of 2022, hundreds of thousands of Cuban men and women will be challenging cultures, language barriers, illnesses, pandemics, sadness, in an attempt to contribute to the family well-being of those they leave behind. It is imperative that both, those from inside and those from outside, those who are on the island and those who are in the dissimilar diasporas, do not lose love, compassion, emotional support, faith, and loyalty for human beings above any possible and necessary material good.

These lines, which blur multiple and daily human dramas, are not a call to sadness, but rather to understanding, to otherness and the ability to put ourselves in the other’s place, to reflect on the complexities and courses that life can take. This text is a message of hope to the Cuban diaspora and their families in this 2022, a way to wish with all the strength of my heart that my uncle be healthy, and that wherever he is, he feels that beyond the ambiguous perceptions of success or failure, there will always be the infinite love of his mother, his brothers, mine…and that love will accompany him through the cold streets of San Francisco or in the luxurious and warm St. Regis Hotel in California.