We really don’t know here what interests our people, at least not with any certainty. Our Cuban “public agenda”, as the sociologists call it, is secret, confidential, and obscure.

We lack independent pollsters interested in measuring and describing our collective thinking. At the same time our press is at the service of our institutions, addressing “on the street” topics only occasionally and on tiptoes. Hence, we Cubans are left to process “what we think we think” with great uncertainty.

In Cuba we have erected that institution known as “Radio Bemba”, or the grapevine, as the most propitious entity for representing ourselves through rumors and thus attaining shared notions about the things that occur or should occur.

Daily we adjust a good part of our world view in response to the list of issues scaling the Bemba hit parade on the streets. Recognizing how important a topic really is and how many people it touches may depend on how near or far we are from the “grieving” parties. Most of the time, the only feedback we get on “public events” comes from our own kitchens and intimate family circles, those discussions that are held peacefully or fought out tooth and nail amid the clatter of pots and pans at the hour of being at home.

We also receive some assistance from the open shouts in the aisles of the buses, crowded to the point of exploding, when a speaker– sane, or maybe not quite – decides to announce their truths; or, perhaps the opposite, when certain ideas are passed from mouth to mouth in increasingly caustic whispers.

In this discontinuous and indistinct flow where oral opinions are configured, we are also helped by the leading role that humor and our popular music plays in our daily doings; even though the jokes and stanzas must keep to the limits established by media censorship.

The information available regarding what we Cubans think and want ends up so vague and imprecise, is so open to interpretation, so much bend and spin, that it’s frightening.

Who today would dare to assert what the majority opinion is, and what its different shades might be, for example with respect to the consequences of last December 17th and the progressive rapprochement between Cuba and the United States? Who can define how people in Cuba see the process of economic reordering, or the performance of a minister, or the perspectives for a new electoral law, and what criteria they base themselves on?

It’s no coincidence that public opinion is barely studied and the results of any inquiries are never publicized, nor is this a mere side product of carelessness. The black hole of public opinion has been the ideal board of operations so that the decision-makers can make decisions that are per se exonerated from commitments that can be measured, quantified or scrutinized. They are accustomed to assuming the good intentions and expertise of those who administer resources and design policies in the context of a state economy. And, more serious yet, they assume that they have consensus.

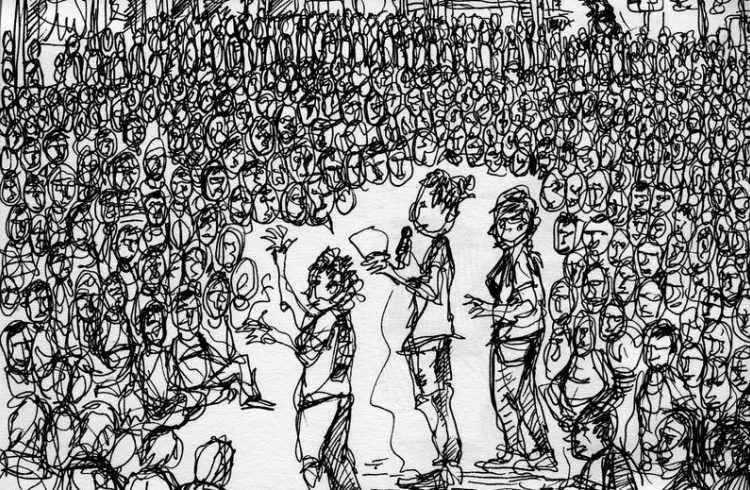

In Cuba, many decisions have been molded in the wake of massive public assemblies. I remember this well, since I was a conscious participant in the meeting process that led up to the IV Congress of the Cuban Communist Party in that parting of the waters that was 1990. The same occurred during the Workers’ Parliaments and more recently during the discussions of the economic Guidelines, and of the Labor Code. In all these cases the quantity of participants was overwhelming as well as the volume of the proposals. But in the end, in none of these experiences was any statistical examination presented back to the public of the criteria offered by the hopeful participants.

The way that the institutions appropriate the balance of public opinion in those events and the dearth of any dissemination of the results – not as a final processed summary document but with the statistical data and without interpretations – distorts the value of these experiences as a consultation.

Within that panorama, the small group of Cubans (about 25% of the population) that connect to the Internet or internal Cuban networks have seen how a new space for expressing opinion has been growing in this virtual zone of life: the zone of commentaries in the digital press where the users, anonymous or baring their chests, from the Island or from outside, all search for the cat’s fifth paw in a rather freewheeling form, despite the lack of custom.

Although almost all of the forums – including of course OnCuba – are moderated, the users of websites such as Cubadebate or even Granma have managed to come ever closer to a vision of the heterogeneous spectrum of opinions that we are developing day by day; and not only regarding strictly political issues. The principal value of these spaces is that they convert the exercise of oral communication into writing.

The written word, even in digital letters, can be recuperated, cited, responded to and for that reason it’s more powerful: an ad hoc gathering place, we could call an agora. And while we are writing, the act of sharing our criteria feeds our own self-image, adding protein to our agreements, forging them in the collective reshuffling between the real world and the virtual one.

Nonetheless, we still see that the world could end while the forum participants argue with wise interpretations or scream their head off without that expression generating any response. The public agenda gathered there, this small evidence of what we think, seems to affect the institutional agenda of the public servants little or not at all.

The majority of times, as has occurred recently, as a result of errors in the University entrance exams, the institutional actors don’t seem to feel themselves under any obligation to reply, and remain elusive. In the face of these many times exemplary debates, those from the ministries or millionaire state enterprises lounge at a safe distance, certain that one byte of opinion won’t affect their course. But the sum of them? On that magnificent day when today’s 75% who are currently not connected become digital citizens, such puffed-up pride might be at an end.