“Without an agrarian reform, there is no revolutionary government,” Fidel Castro proclaimed to a crowd of 150,000 farmers who had gathered in Guantánamo to hear him speak in early February 1959. The announcement was greeted with applause and what one journalist described as “rapturous ovations.” Fidel was not yet Prime Minister and in this case, he was part of a group in the East that had already begun to demand the restructuring of Cuban agriculture. No more than three weeks had passed since the arrival of the guerrillas of the July 26 Movement in Havana, who had marched from one tip of the island to the other, when the Cuban farmers had already become the core of revolutionary policy.

Five months later, on the summit of the Sierra Maestra and surrounded by members of the new Council of Ministers, Prime Minister Fidel Castro signed the agrarian reform law, which is now 62 years old. Every May 17 in Cuba the anniversary of the law is remembered as the day the revolution granted the farmers land, rights and dignity. This interpretation is not equivocal: the reform effectively gave land titles to at least 32,000 families, eliminated illegal evictions and created permanent employment for many farmers and workers who suffered the ups and downs of unemployment in times of the dead season.1

But to limit oneself to viewing land reform from only that perspective is to see only the tip of the iceberg. Beyond the achievements in land distribution to poor farmers or previously deprived of their fields, the law was a starting point for the great changes that took place during the 1960s. The law laid the foundations for a profound transformation of Cuba’s economic, social and cultural life. Its implementation modified private property and inverted social hierarchies. This was the genesis of the conflict between the United States government and the large landowners—many of them foreigners—who owned only 4,426 of the 160,000 farms in the country but who controlled 56.9 percent of the national area in farms, with the nascent government of the revolution in power. For example, it was after the expropriation of their large estates that large U.S. landowners, such as the owner of the King Ranch in Camagüey, Bob Kleberg, who maintained close relations with President Eisenhower and his CIA agents, began to maneuver for the reduction in the purchase of sugar and even for the establishment of an embargo on Cuba. The United States government soon responded with unbridled antagonism against Cuba that, sixty years later, still endures.

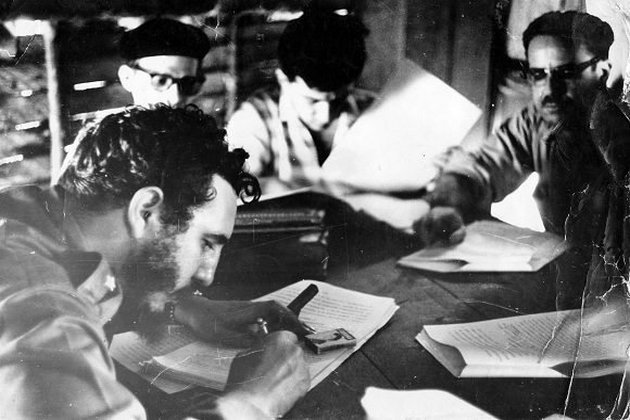

The agrarian reform was also key to other important developments in the revolutionary process. Through debates and the application of new agrarian policies, the government formed by the “bearded men” managed to consolidate power. The agrarian reform put a large number of farmers and agricultural workers at the forefront of the changes that Cuba experienced in those years. The local offices of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), an institute formed to apply the new agrarian laws, were frequently directed and administered by farmers who only months before had been at the lowest level of the social hierarchy.

The consolidation of power was strengthened in the face of the defeat of a counterrevolutionary movement in El Escambray, in its early years backed by the CIA, but which also emerged as a reaction to the agrarian changes brought to the area by INRA. Also through the spaces created to apply these laws, the revolution was radicalized. In many cases, farmers dissatisfied with the results of the local INRA administration exerted pressure for the government to expropriate and redistribute more land than it had intended. While this was part of the application of justice in favor of the farmers, it also resulted in a greater number of landowners and administrators displeased with the direction in which the revolution was advancing. The incorporation of the farmers, who were integrating the institutions and mass organizations: the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), the militias, the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP), also as part of the result of the agrarian reform, helped to counteract the effects of these dissatisfactions, sometimes converted in opposition.

***

It was not surprising that the agrarian reform has had repercussions at both the local and transnational levels. The agrarian reform law marked a step in a long journey of struggles for land in Cuba that began in the 1920s, when farmer associations and federations began to organize against the evictions of land carried out by the Rural Guard, a paramilitary force born during the military occupation of the United States in Cuba, and created to protect the properties of large landowners.

Already in 1890 José Martí had begun to speak of the need for agrarian reform. During the 1930s, when the illegal evictions by private and foreign companies advanced, farmers began to arm themselves. The Realengo 18, a group of farms that covered 4,451 hectares of land in the Guantánamo municipality, was the center of some of these struggles. Armed and with the motto “Free land for those who work it” they managed to defend themselves from the Rural Guard for several years.

The 1933 revolution came to contemplate a series of agrarian changes. And with the Constitution of 1940, a law was finally signed outlawing large estates, but to the frustration of many Cubans, it was not implemented. It is not surprising, then, that upon arriving in the Sierra Maestra in 1956 the guerrillas of the July 26 Movement encountered strong pressure from the local farmers to implement decrees that could support farmers and agricultural workers against abuses by landlords and employers.

In October 1958, before the insurrection ended, Fidel Castro signed an agrarian reform law that governed within the “liberated territories” controlled by the guerrillas. During the following months, Commanders Raúl Castro and Ernesto Guevara applied this law, the so-called Law Number Three of the Sierra Maestra, handing over land and property titles to farmers from Oriente province and the Escambray Mountains.

In early 1959 the pressure exerted by farmer groups converged with the energy of an ascendant revolutionary movement. Already in February and March 1959, while some were advancing, initiating land seizures or trying to apply their own agrarian reforms on their own when there was still no law, Fidel tried to take the lead to stop the disorganization.

***

One more thing that accompanied the agrarian reform law was a wave of widespread rural development. In most of the farms and surrounding areas, there were not enough primary or secondary schools. There were no accessible doctors or hospitals. In the rural houses, there was neither electricity nor sanitary infrastructure. INRA arrived in these areas building houses, towns, schools and hospitals, a process in which the farmers themselves also participated. The houses, made of masonry, had a bathroom and a gas stove, which meant a radical change in the lifestyle of many families.

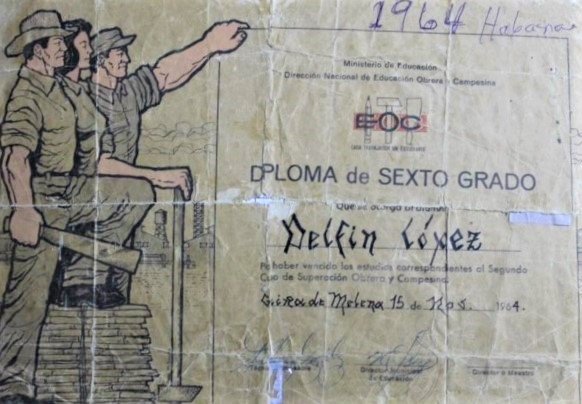

It was thus that when the land titles arrived, university titles also began to arrive. With the help of INRA, the agrarian reform boosted access to education. In places where previously the children of farmers could not even finish the third grade, they started finishing school and even continue their studies. As a result, many young people left their towns to settle in the cities to study university careers.

Two fair and natural processes, but somehow contradictory, then emerged as a consequence of the agrarian reform. On the one hand, many farmer families received land titles or fixed jobs in cooperatives and state farms, which ensured that they were no longer subject to the economic fluctuation of the dead season, and experienced improvements in their quality of life.

On the other hand, schooling transformed the relationship of young people with work. Children of farmers who previously would not have had the possibility of “bettering themselves” were leaving their parents’ farms, land, and agricultural work.

Before the revolution, Francisco García Moreira, a sugarcane cutter from Las Villas went unemployed for eight months of the year just as, for lack of alternatives, his parents and grandparents had. In 1969 he proudly recounted that his daughters had left agricultural work and turned professionals: one worked in a union and another had just traveled to New Delhi on her second mission as a Cuban delegate to the United Nations.

During 2017 I traveled to rural areas of Cuba where I was able to confirm this story in my dialogues with the many farmers I had the opportunity to interview. The history of agrarian reform is more than the history of land distribution or subsequent nationalization that is sometimes blamed for the insufficiency of Cuban agriculture today. It is also that of the farmers who fought for generations to achieve change. That of bitterness and resentments that this change generated. It is the story of men and women who became leaders and revolutionaries, of children who bettered themselves and who became professionals: engineers, sociologists, historians.

What is called “agrarian reform” was, then, multiple processes, dynamic and complex, that defined the course of the revolution and resulted in transformations in almost all aspects of Cuban life. The law that was signed on May 17, 1959 represents a piece of that history, both a culmination of decades of farmer struggles and the driving force of new battles that have not yet concluded.

Note:

1 Dead season: Time between sugar harvests where much fewer workers were needed in agriculture and hundreds of men wandered in search of any job to support themselves and their families.