It was not art, but nostalgia, the thread that pulled filmmaker Ernesto Daranas (Havana, 1961) to launch a rescue and salvage operation of the work of Nicolás Guillén Landrián (Camagüey 1938-Miami, 2003).

The son of mountain teachers — his mother’s last name is Serrano — he lived the experience of the Sierra Maestra, the incubator of Fidel Castro’s lightning-fast guerrilla war in the late 1950s, until he was 5 years old. Back in Havana and still a child, Daranas was perhaps the only one who happily endured, in the neighborhood cinema, the tiresome repetition of Ociel del Toa (1965), a documentary jewel by Nicolás Guillén Landrián (NGL) that served as filler in film batches in case the movie of the day failed

“The many times they put it on caused the public to start whistling; but I was very fond of the documentary. It brought back memories of my childhood in the Sierra,” he says from the other end of the telephone line when talking with OnCuba from his home in Old Havana.

As much or more than his cinema, the life of NGL shows signs of a novel. His mother, a designer, a friend of Lam and Ponce, avant-garde painters. His father, lawyer, law firm owner. His uncle, the famous communist poet Nicolás Guillén. He studied painting, and then Social and Political Sciences at the University of Havana, where he conspired against the Batista dictatorship. He abandoned the career to dedicate himself to radio locution.

He was unemployed when in 1960, expelled from the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP) and the School for Diplomats, he entered the Cuban Institute of Cinema Art and Industry (ICAIC) advised by Juan Carlos Tabío. He started out as a production assistant, and Joris Ivens and Theodor Christensen were quick to mentor him as they noticed the rookie’s talents.

Nicolasito, as he was called, filmed his first works as a director: Patio arenero, Homenaje a Picasso and Congos reales. In total there were 14 documentaries. Coffea Arábiga, the most controversial of all. In a row, they can be seen as the exquisite corpses of the surrealists, despite the didacticism of some.

In the mid-1960s, under suspicion, he was in and out of interrogations, psychiatric wards, correctional farms, house arrests, electroshocks; ICAIC itself fired him and reinstated him. In the end, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, which could explain the chaotic language of some of his pieces, taken as genius and postmodern.

Definitely expelled from ICAIC in the early 1970s, he lived from his painting. Gutiérrez Alea, García Márquez, Pablo Milanés, the British Embassy, among others, were his market.

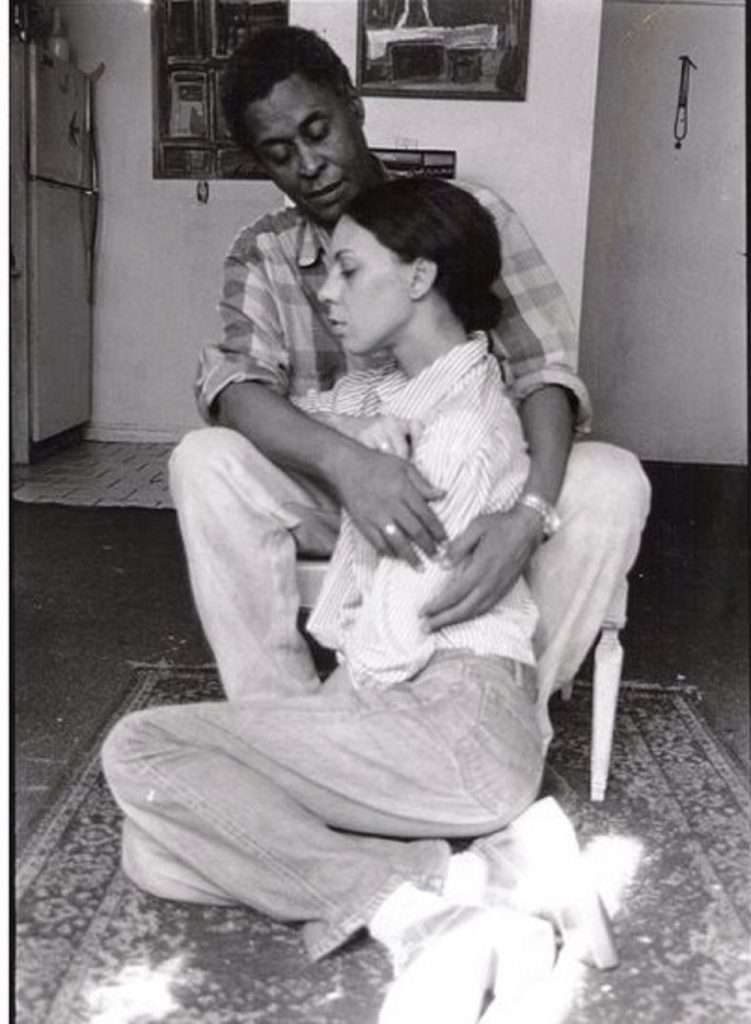

In 1989 he went to Miami with his second wife, Gretel Alfonso. From motel to motel, they survived thanks to the canvases he painted, by the hundreds. In the so-called capital of exile, he filmed Inside Downtown, in 2001, together with his countryman Jorge Egusquiza, a dive into the city’s underworld.

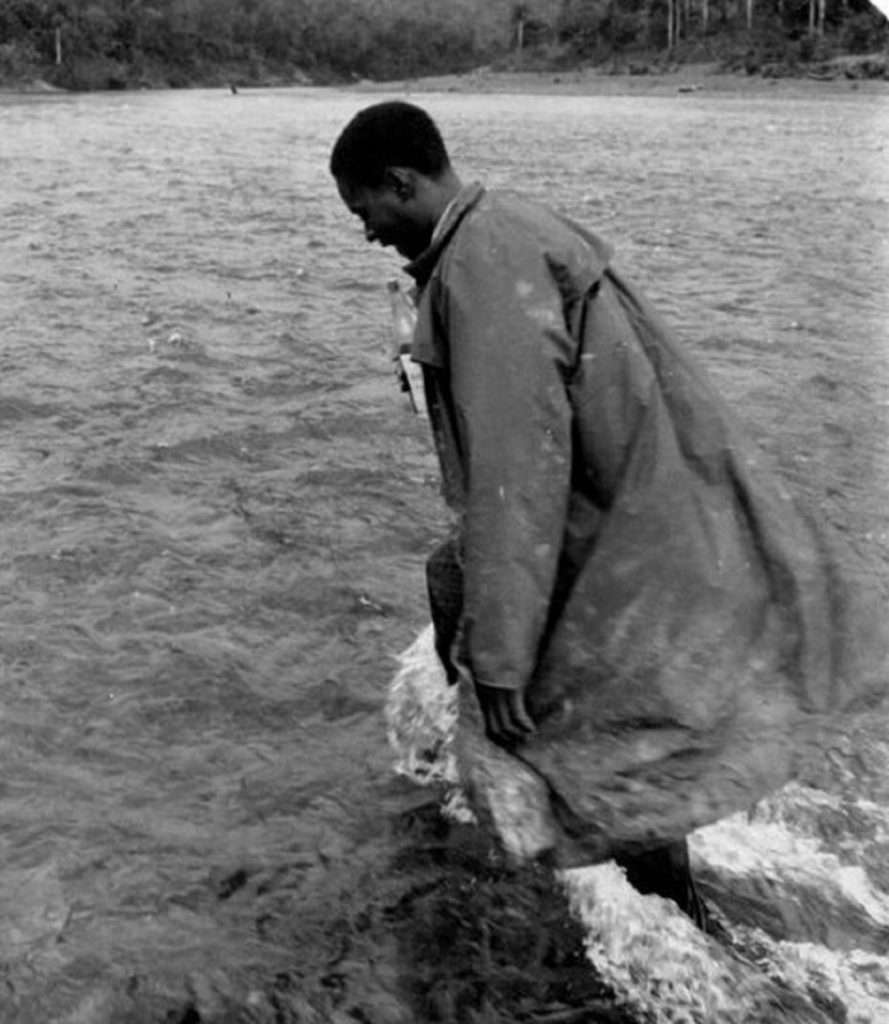

When reviewing the stills of his films, you can see him dressed in a buttoned jacket under the sun of Baracoa, on the eastern end of the island, where temperatures are close to 35 degrees in summer, and in the undergrowth of his anecdotes he tells a woman who, suspicious, interrogates him about the permission for a street filming. Dressed in a suit and tie, NGL blurts out: “Ma’am, we’re from the Central Intelligence Agency, don’t pester.” Stunned, the curious woman left. That time, the Kunderian joke didn’t put him behind bars.

Five months before pancreatic cancer ended his days, the Young Filmmakers Showcase sponsored by ICAIC premiered, on February 22, 2003, most of his titles in the “Premios a la sombra” section. It was his first institutional resurrection. It was quite a reparation and an audiovisual shock for the attendees, upon discovering a “galaxy animal.”

The second vindication will come 19 years later, at the 43rd edition of the International Festival of New Latin American Cinema, with a retrospective of his documentaries, a dissection table around them, and the premiere of the material Landrián, by Ernesto Daranas, on December 3, with photography by Ángel Alderete and editing by Pedro Suárez Boza.

In the midst of a hectic schedule, the director of Los dioses rotos (2008), Conducta (2014) and Sergio & Serguei (2017), agreed to talk about his documentary, his film archeology work and the importance of a man who saw himself “always…in the vortex of alienation,” as he confessed to filmmaker Manuel Zayas, author of Café con leche (2003), a documentary in which Nicolasito recounts, shortly before his death, his life as a film.

What makes NGL’s cinema a cult for several generations? His ideological misplacement, his brutal, mocking and lyrical aesthetics, his gaze that moves, pendulous, between lucid and schizoid, his cryptic darts or his opulent slights to political correctness?

The first explanation for this cult lies in his talent. We of course can talk about the schizophrenic, the marijuana user and the prankster, but that is not going to explain the respectful and honest way in which he looked into the eyes of the Cubans of his time. For me that is the first. I find it admirable how the skepticism and political irony that exudes a part of his work never loses sight of respect for the self-esteem of the Cubans, his racial drama, his spirituality, his helplessness in the face of pharaonic endeavors such as the Cordón de La Habana or the normalization in our lives of those Stalinist-like ceremonies and assemblies that we find so brilliantly questioned in his cinema.

It is said that the Cuban documentary of the 1960s and 1970s had in Santiago Álvarez a teacher of historical certainties and in NGL a challenger of a reality assumed as a permanent imbalance. How far is that dichotomy valid?

In a country as politicized as ours, it is inevitable that any analysis, on one side or the other, is marked by politics. Santiago and Landrián were two very different filmmakers and people, but what is indisputable is their talent and the place they deserve among our most important filmmakers. The work of each one is essential to understand the history of our cinema and why we are what we are as a nation and as a culture at this time.

We know the sentimental origin of your connection with the work of NGL; but how did this rescue expedition come together and what doors did you have to knock on?

The ICAIC is responsible for the Archive in which his films were, so that was the first door that had to be knocked on. I knew that others had tried to restore Landrián’s work outside of Cuba and that the negotiations had not prospered. That is why I asked experienced editor Pedro Suárez to design a workflow for me to do the restoration in Cuba. That was the original idea and with it I went to see the president of ICAIC, Ramón Samada, who offered us all the necessary support.

Then the pandemic arrived, finished off by the Task of Reorganization, and all the design that we had done to finance the restoration went down the drain. So we had to go out and look for international support.

Did you know about film rehabilitation or were you a beginner?

All I knew was that Landrián’s work was being lost. The path to follow was shown to me by Pedro Suárez. Then came the addition of the determined contribution of Luis Tejera and Roberto González, from Aracne DC, who have been in charge of the restoration in Madrid.

What picture did you find when you set foot in the ICAIC vaults?

Bleak. Film material is very volatile and requires very specific and expensive conditions for its conservation. That is why it is so important to digitize all the films that are deteriorating in the archives as soon as possible. This is something that must be done according to international technical standards; especially if the objective is not only to archive, but also to restore. As long as that is not possible, our film heritage will continue to be lost.

At least for now, the steps that have been taken to address the problem remain insufficient.

Exactly what did you find in the Archive and under what conditions?

We found ten Landrián titles in different states of deterioration. Also unpublished photos and documents. Some of his important documentaries were not found. It does not necessarily mean that they have been lost. What happens is that many of the film cans are so damaged that it is not possible to determine what work they contain. Unfortunately, the Archive does not even have the necessary means to carry out the visualization and classification required in these cases.

Is NGL a cursed creator, a misunderstood, iconoclastic and envied genius like so many others who have suffered reprisals from officials or the cultural bureaucracy in power for such a condition in the world?

When it comes to the subject, I don’t need to look at what has happened in other parts of the world. I do not believe that the mistakes committed and those that are committed in our country respond to a “universal logic.” Nor do I believe that the circumstances, however tense they may be, justify excesses. The reprisals that Landrián suffered were suffered in Cuba and the most serious thing is that this modus operandi of our politics and our culture remains in force.

The criminalization of dissent, forced exile, corruption, the suppression of basic freedoms and censorship itself are what explain, to no small extent, the brutal exodus of young people we are suffering. A significant group of our most talented filmmakers is part of the stampede. I know them, exchange with them and many would like to be making movies in Cuba. They did not emigrate because of the blockade, many have left because there was a N27 and a J11 from which the same demons that Landrián had to face at the time were unleashed. Therefore there are no cursed creators, in any case there is a cursed recurrence in the same errors.

Once the work is finished and the NGL work is returned to the present, what will happen to it? Will it have a second chance to be publicly recognized and reread in light of the times?

I don’t decide those things; but of course we are working to make that happen.

Are your efforts and those of your team equivalent to a late but necessary rehabilitation of the work and the person that was NGL?

The truth is that nothing we do now can restore the injustices Landrián was subjected to. They can make a statue of him in front of the ICAIC or sit him in a park next to Lennon. Nothing can give him back at this point what was taken from him or what was taken from us of what could have been the rest of his work in Cuba.

As for the historical rehabilitation of Nicolás Guillén Landrián, that is a merit that corresponds to many other filmmakers and critics, who for more than 20 years have been placing his work in its rightful place.

Our goal now is to return that work to the place it deserves in front of our audience. With Landrián there is the paradox that, despite being one of the Cuban filmmakers about whom more has been written and debated so far this century, the Cuban public barely knows his films.

How was your documentary Landrián, which we will see at the Havana Festival, conceived and what will it make us know and understand?

It is a documentary aimed precisely at that great public that does not know the life and work of Landrián. It is led by the testimonies of his widow, Gretel Alfonso, and photographer Livio Delgado, who allow us to discover the essence of the man and the artist named Nicolás Guillén Landrián. At the same time, the film recreates passages from the search and restoration process of the ten Landrián documentaries on which we are working.

It is paradoxical that the 43rd edition of the Havana Festival pays tribute to NGL, kept on ice for decades, and at the same time resorts to a game of maneuvers to ruin the participation of an uncomfortable film (Vicenta B), presumably and ultimately due to similar arguments with which they threw the work of NGL into the common grave of oblivion. What do you think about that?

Vicenta B is an award-winning film in the first call of the Fund for the Promotion of Cuban Cinema and has been co-produced by ICAIC. Therefore, those who have withdrawn it from the official selection have chosen to ignore the autonomy of the Festival, the authority of ICAIC and the confidence that filmmakers need in the nascent Fund.

As has happened on other occasions, the true censors remain in the shadows and it is up to the Festival and ICAIC itself to yake responsibility for this.

The objection in this case does not seem to be precisely about the film, but the rebellious attitude of Carlos Lechuga and, by derivation, of Claudia Calviño, the producer. Basically, they seem to expect from both the coherence and restraint that was not shown to them when they were subjected to all kinds of tensions due to their work. They are questioned for having been “disrespectful to the Revolution.” This, in a country where those who dissent have been branded as traitors, worms, scum, annexationists and working on behalf of a “soft coup,” while they are publicly smeared and slandered in the media.

It is a clumsy and exhausted game that, of course, serves the table for many artists for the political performance, which is one of the weapons with which art and the artist confront the established order, especially when that order tries to condition their freedom of expression.

Landrián no longer lives. Lechuga does. Is death an advantage in these cases?

It should not be like that. It is a total inconsistency.

How much does the decision that has been made with Vicenta B damage the Festival and the return of Landrián’s work to our movie theaters?

The Festival and the Cinematheque had been seriously preparing the return of Landrián to our theaters. When making any decision, it should have been taken into account that Nicolás Guillén Landrián is invited to the Festival and that the analogies between what happened to him half a century ago and what is happening again now would be inevitable.

Would you agree that any discriminatory exercise ends up being a marketing operation for the excluded work and author and, therefore, becomes its own absurdity?

Of course. It is clear that they do not want to accept that, more and more, Cuban cinema will be the one they censor, and that Cuban filmmakers will be the ones they try to silence. The paradoxical thing about the case is that the Landrián documentaries that we will see at the Festival exude commitment and respect for our uncertainties, dreams and sleeplessness as a people, as do films like Vicenta B, Santa y Andrés, Melaza and others that have been censored or made invisible for over sixty years now.

Of course they are questioning works, but hardly any of them are political pamphlets. Censorship itself is what has complemented our reading of them and has given them a good part of their final meaning. In this sense, as you point out, the censors end up being the great promoters of a political marketing that leaves the positions they claim to defend in a very bad light.