She is a Havanan, model 1977. She graduated in 2000 in Informational Design at the Higher Institute of Design (ISDi), a prestigious Havana institution. Since then she has developed her career in state institutions related to culture and, for some time now, as an independent creator.

Laura is not close to turning 50 years old, therefore no reason to celebrate an anniversary. She hasn’t won an award recently either. Neither has she been involved in any of the many thunderous controversies of these days. She does her job exceptionally well, and that’s reason enough to arouse the journalist’s interest.

Mother of two children, wife of Pepe Menéndez, a leading designer in Cuba, her art deco house in El Vedado is also a laboratory where several artists’ books are designed at the same time. Each one separately and as a duo have reached the ideal state in which they do not have to go out looking for clients; they are the ones who are sought out. Laura, like Pepe, belongs to that rare species in the Cuban ecosystem that provides solutions instead of problems. She gets involved in projects in a visceral way, assumes them with responsible enthusiasm, lets herself be won over by the joy of contributing to creating useful and beautiful objects of great cultural significance.

How, why did you join ISDi? In your case, can we speak of a “correct” vocational orientation? Were you particularly interested in the visual arts? Did your family environment encourage or decide your penchant for design?

I always liked to draw and I was good at manual activities and things that involved creativity. I enjoyed it a lot since I was little. My family encouraged me to attend visual arts workshops and circles of interest, and I loved it.

I also liked many other things; at that time there were circles of interest for everything. I learned to take care of calves, to milk cows, to organize a museum, to be a restaurant waitress, to create sound effects for the radio, to decorate cakes…. But what I liked most were the plastic arts workshops.

However, I always understood all of this as fun, as a pastime…. I suppose partly because my parents were chemistry professors at the university, but also because the regular education insisted that the most coveted path should be the “mainstream” university majors.

When I was finishing junior high I found out that a friend had taken the exams to study at a plastic arts academy called San Alejandro. I felt a little cheated, because I had no idea that this could be studied “seriously.” But that was fleeting, I continued on my little path.

I found out that the ISDi existed when I was almost going to do the entrance exams, in twelfth grade. Despite the fact that it had been created in Cuba for about ten years, the Design career was hardly known at that time. It did not happen like now, when it is not only known, but also coveted.

At that point, I still had no idea what I was going to study, I only knew that I would go to university. My preferences were very different, and I think that speaks of the fact that I did not have a very defined vocation. I thought of options as distant as Architecture, Psychology, Microbiology and Mathematics. I must admit that I was not inclined towards any of them too strongly. When they explained to me what a designer did, I finally began to feel that I had a clear calling for something.

The process was somewhat dizzying; I will never stop thanking for having had a mother who was involved with my vocation and my future with all seriousness.

I arrived from the school in the countryside where I was studying senior high on a Friday, saying that there was a career “called Design, which was about creating things and you had to know how to draw.” My mother listened to me, and a few days later she put me in front of an ISDi professor; she obviously did not keep him in a drawer at home, that is, she looked for him until she found him. He explained to me what the designer’s profession is. And there I fell in love, until today. Not of the professor! Of the career. The entrance exams, which were then only for aptitude, were intense and difficult. Two full days of tests and more tests, some of them qualifying. None looked like what we were used to. You had to demonstrate things that were not related to the ability to reason, memorize, repeat…, but with abilities and talents. It was at the same time a lot of fun. When I left, after the last test, I did so with the conviction that if I was not admitted that year, I would try as many times and in as many ways as possible, because that profession was mine. They admitted me, I was saved.

When you started, did you have an idea of what informational design was? What did the school represent for your development? What are your most pleasant memories of the Institute in your student days? What aspect would you have liked to be different?

I had a superficial notion of what informational design was within the rest of the specialties. Luckily, the first year was common for all, informational or industrial design was studied only after the second year. The first-year exercises were also aimed at making us understand the difference. I liked both, but I was better at the informational ones.

On the one hand, imagining things in space was not my forte; on the other, I was fascinated by communication, messages. A designer works with the function that his design object will have. In the case of informational design pieces, an important part of that function is communication. I like that.

The career was not easy for me, especially at the beginning. The first months were hard. The change of learning mode cost me. It was not a matter of doing what I had done until then and it had gone well: attend classes, read the materials, do the exercises, demonstrate knowledge in a written exam….

Learning a profession with an artistic component implies other forms, a lot of workshops, hours of creation and realization, a lot of self-knowledge, rhythms, moods and their influence on creative results. And also a great ability to take from everywhere and combine everything, to always be observing, generating, thinking, involved with the project. An artist is creating all the time, or accumulating experiences to create later with them. It is unavoidable.

Despite that, I was fortunate to enjoy a lot while learning, and that experience was the most valuable of those years for me, the enjoyment. Even so, there were thousands of things that I would have liked to learn and did not learn. At 20, you don’t have the maturity to be clear that everything they are giving you is an invaluable arsenal. Nor were there the material or human resources to teach everything useful or necessary. And design is not just art and message; it has to be able to be produced, be profitable, last, pollute as little as possible, be optimal. There were also skills that I could have acquired and didn’t. Illustration is one of them. After me came a wave of illustrators that started more or less with the creative group Camaleón. The professor who led that group, Nelson Ponce, was my study colleague. He was a couple of years older than me (and still is), so he wasn’t my second- or third-year professor, which is when illustration is taught. So I did not coincide with that phenomenon, which would have delighted me and, probably, influenced me as a professional. But I maintain that the ISDi was an excellent school. There I learned to be a designer, and I learned that one never stops learning.

For six years you taught typography and basic design at your alma mater. Do you have a good memory of that time? What made you decide to leave the teaching profession? Are you willing to retake it?

The experience as a professor was beautiful. I have beautiful memories. I think I was a professor, basically, for two reasons. First, because I had a kind of debt to the Institute, to the students who would come after me. It was right and fair to give them a part of what I had received. Second, because my parents were professors, and I somehow inherited that need to share what I know. In the end, both reasons are more or less the same, something that is in me.

I also discovered how beautiful it is to learn by teaching. The responsibility of teaching forced me to study hard, to better understand things that I had more or less understood before, and to look for answers to questions that probably no one would ask me. I was almost the same age as my students and had been in their position only a few years before. The relationship was very organic; I felt that I was useful to them at the same time that they were useful to me.

However, “earthly” things took their toll on me and led me to decide to move away. Bureaucratic structures, absurd provisions and an economic remuneration that was insufficient to support a home with two children led me to take a break from teaching that I never retook again. I would like to go back to teaching, but I feel that the reasons that made me quit are still there.

I had a wonderful experience when my children were in elementary school. For them and their groups I was a professor of something to which I never gave a name. It was plastic arts, creativity, “inventing,” a game, all at once. I put together the programs based on what they needed, would enjoy or find useful, and considering the learning objectives of the years they were studying.

Their schools opened their doors to me and I went once or twice a month to share creation and learning exercises. I didn’t earn anything, of course, and most of the time I had to juggle my work time to free up the afternoon that corresponded to my classes. It was fabulous. Working with and for children is one of my greatest passions.

I have had the opportunity to work with ISDi graduates, and I have noticed a high professional level in all of them. Is it coincidence or, on the contrary, is it a school that is on a par with other very prestigious ones on an international scale?

I think that the ISDi is a design institute of a good international level. It is noted by the presence of Cubans among the winners in international competitions, or among the juries, or in exhibitions, and by comparing what Cubans propose and what those of other nations propose. Also by talking and exchanging with professionals trained in other countries, sharing workshops with them, attending biennials where Cubans and non-Cubans give lectures about what they do. And finally, by verifying that the majority of designers trained at ISDi succeed in the profession when they move to other countries.

I know Cuban designers who have been creative directors in transnational companies, who have had important responsibilities in universities and events, who found companies, and these are good and successful…. And I am talking about developed countries, with complex infrastructures, where design is valued and respected.

Sadly, that talent is less and less noticeable here. The exodus of young professionals reverberates throughout society, and the designer community is not spared. I have spent 22 years as a graduate watching many colleagues leave, but in recent years the trend has clearly accelerated. I hardly know of any young designer, who I have at some point identified as a “promising recent graduate,” who stays here for more than a couple of years. They leave.

Is there a full understanding of the importance of design in our society? Do the decision makers, at different levels, make sufficient use of the potentialities of the designers?

Our society is poorly educated regarding the importance of design. Most people think that design is “making things pretty,” that they look cool, that they flow in the trending way.

The importance of the function of the design object ― be it a book, a lighter, a wallet, a scalpel, an educational campaign ―, the capacity of this object to be “used” in an optimal, comfortable, convenient way, is not usually mentioned when talking about the responsibility of a designer in the creation of the object. Nor is there any talk about the importance of the object being the result of an optimized process, in which the least possible is wasted, or the most durable or adapted to our climatic or cultural conditions was chosen, over the brightest or most similar to how the Americans do it.

Many of the decision-makers enter this universe of limited understanding, from ministers or senior managers to local administrators or directors. The best design solutions are most often found in the cultural and private spheres, and I think this means that there is where a greater understanding of what design is and is worth exists. But there’s a long way to go, a long way.

Do you like multidisciplinary work? Is it difficult to constantly have to confront ideas with a team of colleagues from different specialties?

I love it. It has its good and bad parts, but I’ll stick with the good ones. We are social beings, we evolved to cooperate productively. When a group of people with diverse abilities and tools articulates in order to achieve something, the result is like an act of magic.

I learn a lot with each team project. It is very comforting to see how everything is put together, and to discover in the result what one knew and put in, and what one did not know and the others put in. Of course, sometimes it is difficult for me to adapt to the methods or rhythms of others, but I also try to learn it. Being versatile and open is a life skill. Sure, I also sometimes learn what kind of work I don’t want to do again, or what kind of person I don’t want to work with again.

I suppose that the interrelationship with the artists for whom you have worked in the design of their books has been, in general terms, enriching. What positive aspects have you obtained from the exchange? Is it difficult to work with artists? Are they “special beings”?

The interrelationship with artists has been very enriching. When I left ISDi, I maintained that design is not art. That’s what I learned. The practice of the profession has shown me that it is, although it has areas that are not art at all and are just as design related as others (and this is an endless controversy). Working with artists has also helped me understand that.

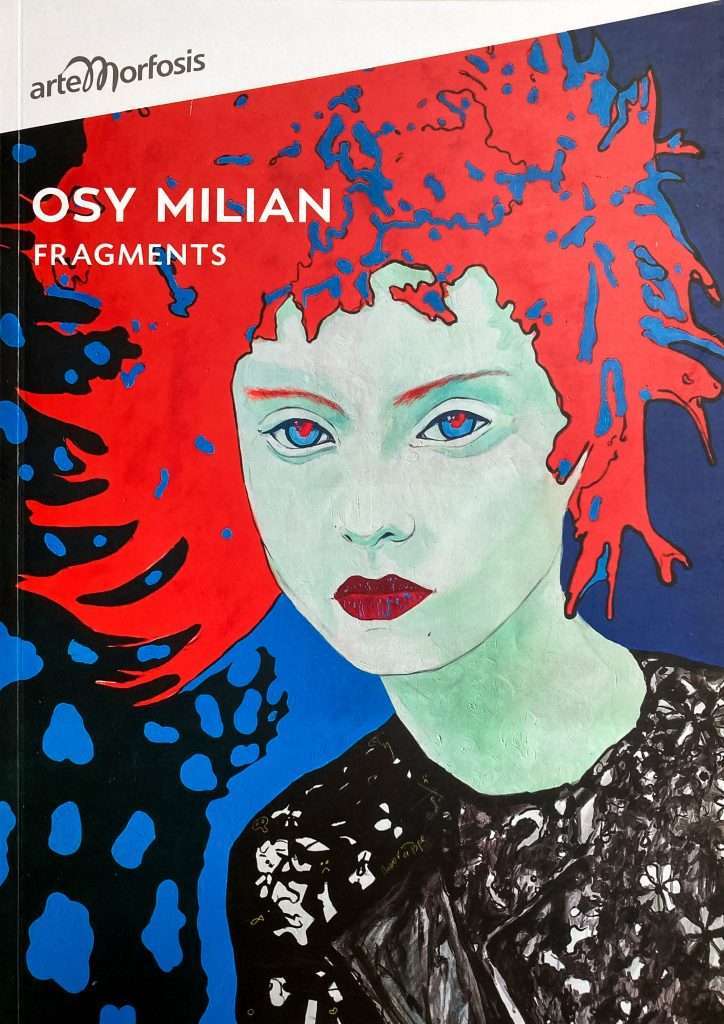

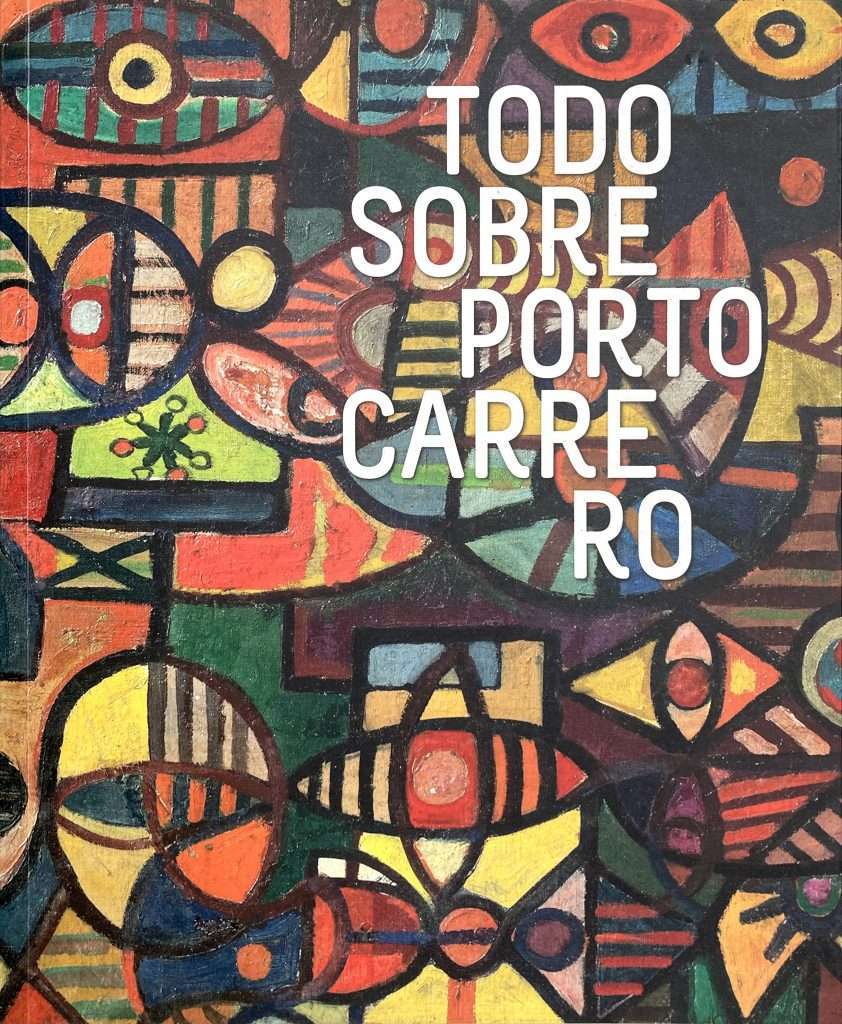

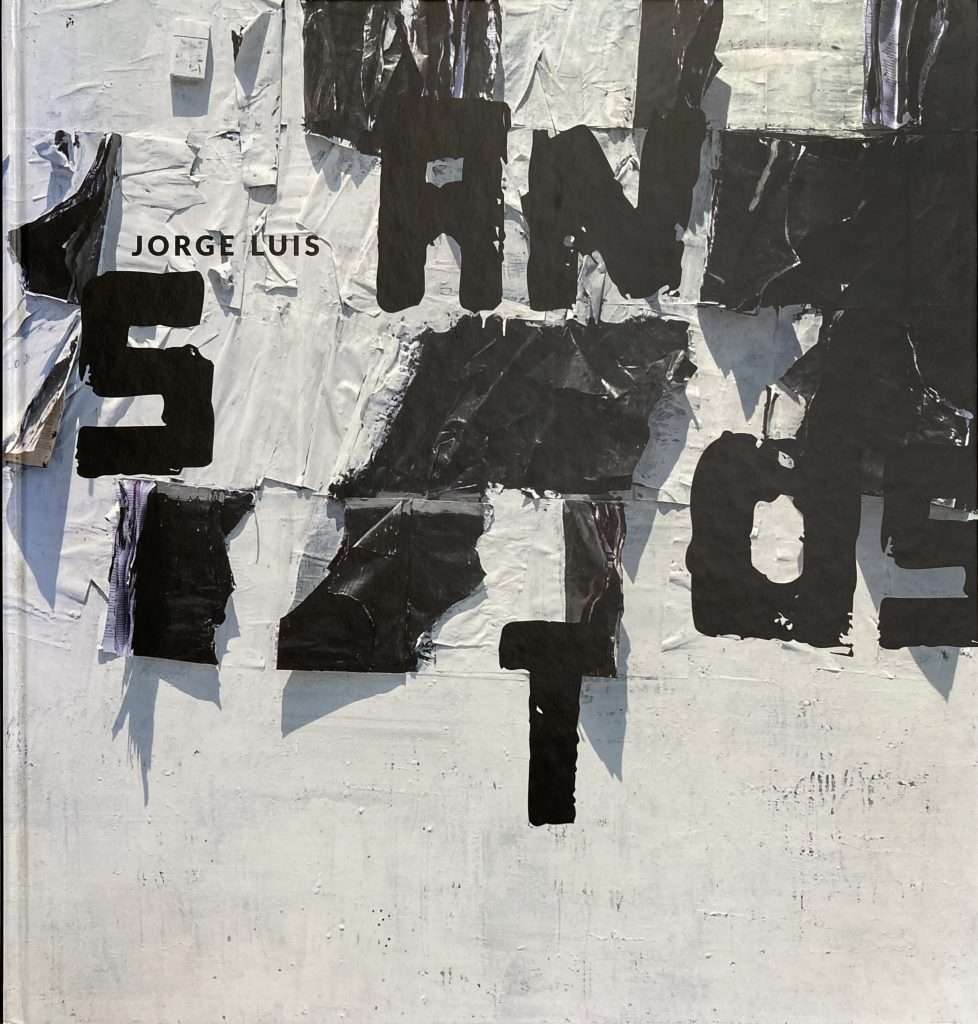

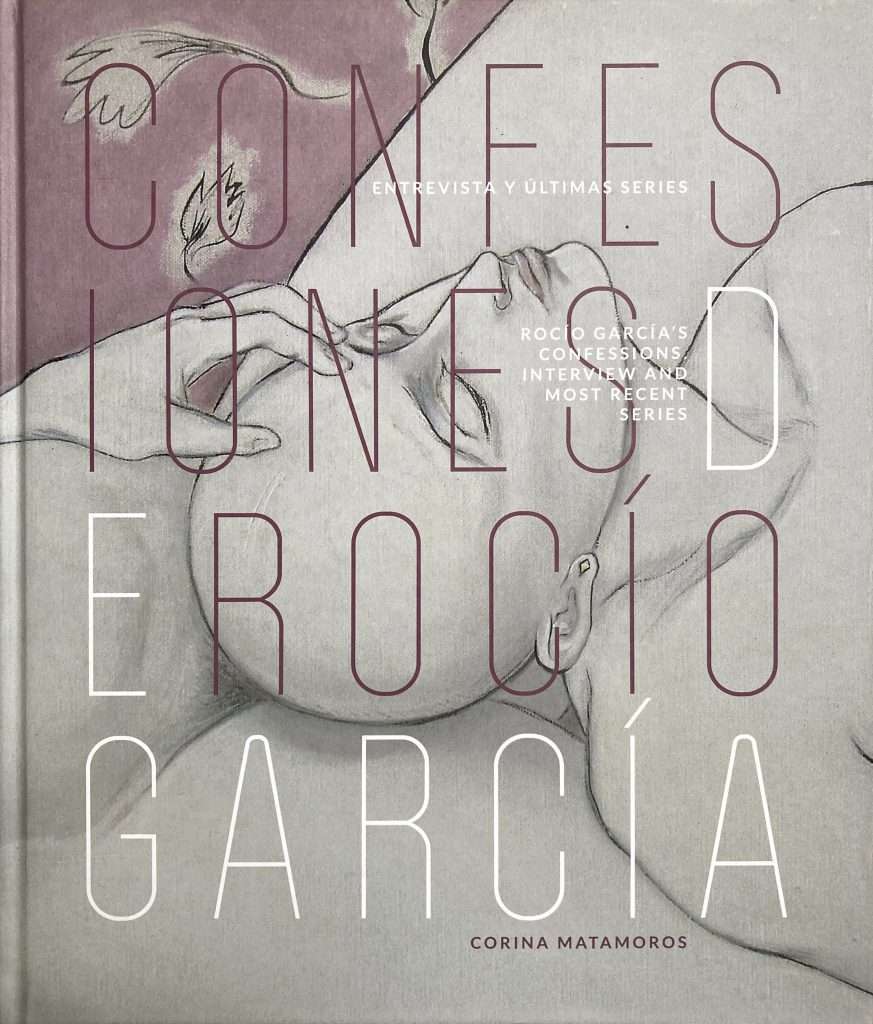

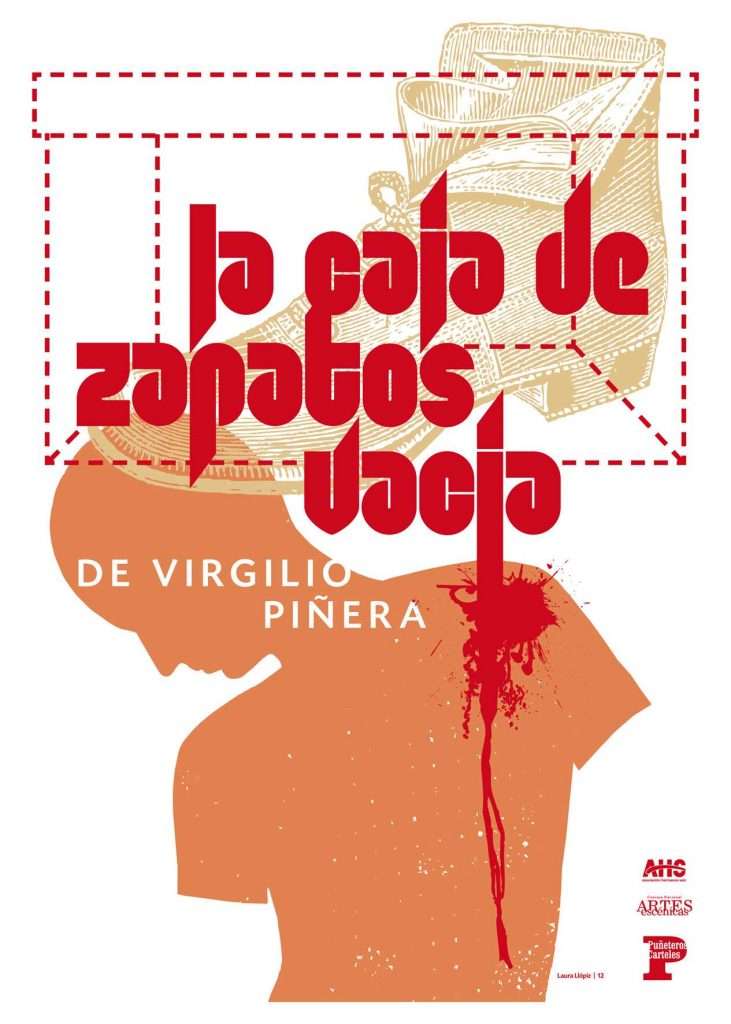

Most of my professional experience has been designing visual arts books and catalogues. You might think that artists are capricious or foolish, but I attest that this is not necessarily the case. On the contrary, I have identified at least two advantages of designing for them. One is that they express themselves with images and dominate this world. That makes communication easier. They understand color, composition, shapes. They have a feeling to understand what I am trying to propose to them. The other is that, since they are creators, they approach each other’s creation with respect, something essential for a favorable result.

Design is almost always the response to a commission, but it is a creative response, which emanates from the designer’s talent, experience and dedication, and depends a lot on communication between the designer and the person who makes the commission. With artists this communication usually flows very well.

What is it like to create and live with a designer who is also the father of your children?

It is many things, but, above all, it is comfortable. We love each other and we like to do things together. Obviously, many more things than designing, but designing is one of them. Everything flows. We talk about the fact that the artist is always with a part of the brain in his creation. I wonder how exasperating it can be to live with an artist without being one and deal all the time with the fact that that person spends part of the time in a parallel world. I know designer couples who don’t get along very well working together.

Pepe and I get along very well, but we get along well in general. Even so, we do not share all projects. In fact, we do more projects separately than we do together. There are people who perceive us as a team, and we enjoy it. There are others who prefer to work with one or the other, and we enjoy it too. One of our strengths is knowing that and acting accordingly. But while it was always comfortable working together or working on the same thing, it wasn’t always easy.

Initially, I found myself dealing with a challenge that, I confess, I did not anticipate. It’s not just that Pepe Menéndez, my life partner, is also a graphic designer. It is that he is an excellent graphic designer, recognized, with a well-earned prestige that he already had when we met.

There is a difference of more than ten years between us. I was a recent graduate with a great desire to do, to swallow the world, as usually happens with young people. He was an established and respected designer. If we add that he is the male and I am the female, the formula is ready. The machismo that our society experiences put a good flavor to the matter. All of a sudden, I was “Pepe Menéndez’s wife.”

That opened several doors for me. I accepted it and celebrated it, although sometimes it is more comforting to open the doors on your own. But the point is what it meant to walk through those doors with the burden of being a woman, “the wife of.” I didn’t want to be anyone’s wife, especially professionally, but I snuggled up to a “someone,” and it took me years and energy to get recognized without first being associated to him. Several things helped me. One was to identify our differences as creators and our strengths as a team. There are things that Pepe knows how to do well, and I don’t. There are others that I know how to do better than him. And there are things that work out well for us because we do them with four hands and two brains.

In addition, it was very good to feel his recognition and respect for my work from the very beginning. He encouraged me when I was very inexperienced, and he continues to encourage me twenty years later when I feel overwhelmed or exhausted. Admiring each other is essential for a set of two to be a couple; and it is, fortunately, one of the first check marks I make when I describe ours.