It started as an option now it is a terrible plague. I’m talking about Todo x Uno (Everything for a one dollar) in literature, one of the most frequent strategies for purchasing books in Cuba.

The first step was taken by a group of sellers in Old Havana: booksellers at the Arms Square. They range from Fourier’s phalanxes to anarchist syndicalism, with intermediate variants like sects, parallel markets or secret societies. They do all kinds of work: they do leather binding; staple; restore; change damaged covers with 250 gr Bristol cards, decorated cedar; etc. The ad reads: “A bargain! All by Chavarria for one Padura” (that “Padura” was, obviously, at that time, any novel of the “four seasons”). The add aimed at encouraging the exchange of books, a fuel capable of bringing people closer to a kind of exchange that is based on consumption, which is in jeopardy in our literary scenario.

Which Cuban authors have the highest demand on the shelves of Cuban book gangsters?

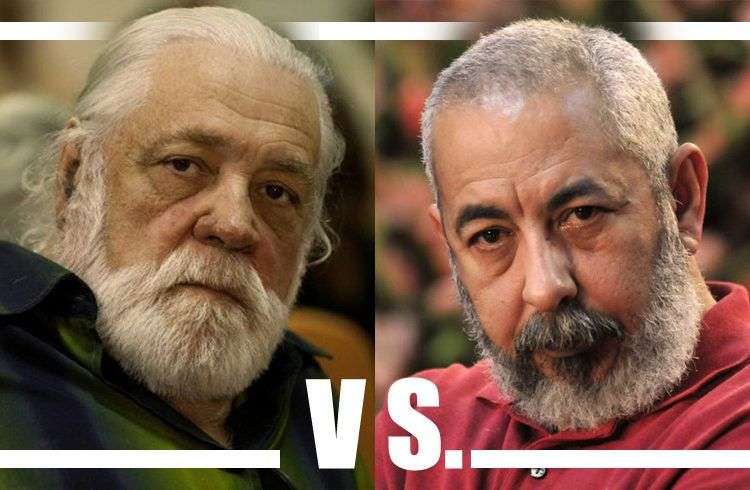

First: Leonardo Padura, il divo. People would pay anything for El hombre que amaba a los perros: 15, 25, 35 CUC in Revolico. Yet, this numbers are nothing in contrast with other temptations they can also get in that website: “a 16 GB iPhone 4S, with jailbreak, per all books by Padura”; “a Gouda cheese per Herejes”; “an 8 GB mini iPod per El viaje más largo, Un hombre en una isla and El hombre que amaba a los perros”; “I want to buy El hombre que amaba a los perros”; “I sell two secondhand books of El hombre que amaba a los perros”. The book takes all the energy in the system. Nothing else is sold. Everyone wants to buy or sell books by Padura. Eclipsing his colleagues with a great career in Revolico seems to be Padura’s fate, something no one in his closest group of friends would have ever dared to foresee while he was studying Philology at the Arts Faculty at the University of Havana.

Second: Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, the Pop King in the municipality of Centro Habana. Even tough time has gone by since the boom of Trilogia sucia de la Habana, this tropical Bukowski –as baptized by Roberto Bolaño— still maintains a nice uppercut. “Most my buyers of Pedro Juan are from Centro Habana”, says El Chino, one of the best dealers at the Arms Square, “people come looking for the Cuban reality in the mirror, daily life”. Right away I had a thought: reading has always been judged as an evasive practice, but it turns out that Pedro Juan’s readers don’t want fiction, but reality. They want to enter in catharsis, to dope with non-fiction. Pedro Juan’s readers are still Aristotelian, they don’t know about drifting apart. Bolaño used to say: “I know about readers who wonder when he can writeif he is fucking all day long”. Fucking or writing, that’s the question. Shakespeare had never been so close.

Third: Amir Valle, with a single book: Habana Babilonia. It spread in Cuba via email; it moved hand from hand in photocopies. It is impossible to know how many cartridges the Cuban State had invested in this viral book. Amir didn’t achieve such success with any other of his pieces. Many people’s efforts for getting another of his novels are but an illusion, the ratification of the effect Habana Babilonia had in them.A tragic destiny that of Amir del Valle: his readers in Cuba, are apparently, those Pedro Juan Gutierrezlacks.

Fourth: Daniel Chavarría. Despite the many re-editions of the books by this Uruguayan writer who is always present at Havana’s International Book Fair, neither Adios muchachos, nor Priapos can be found in any bookstore. Not to talk about Viudas de sangre (has anyone thought about the number of pages of Viudas…? In the Cuban literature it is only surpassed by Misiones by Reinaldo Montero). It’s incredible the preference of the readers for Chavarria’s model. People stop reading Rubem Fonseca (El gran arte), Ricardo Piglia (Blanco nocturno), Cristina Rivera Garza (La muerte me da), in order to read Chavarria. Someone will say Cubans will gladly take the risk of keep on reading Chavarria, yet it is optimist to talk about a simple “risk” as hundreds of Cubans keep on reading his novels habitually. And the worse: they reproduce among each other. They have created an ecosystem: the Chavarria Park, an incestuous reading canton with DNA of the Uruguayan. The consequences of genetic redundancy: ectopic testicles, harelips, spina bifida, duodenal arteries, etc. –which are noticed in the variety of congenital malformations in certain Latin American territories—are already known. On the etiology of these malformations Umberto Eco noted in La definicion del Arte: endogamia.

One of the causes of aesthetic lack of knowledge of the public is the result of that stylistic inertia in the fact that readers or spectators only enjoy those incentives that satisfy their sense of formal probabilities (so, they can only appreciate similar melodies to others they have previously heard, obvious lines and relations, “happy” endings).

I think it is important to clear out that if that is true, Daniel Chavarria’s readers will soon become spectators of Tras la Huella (a Cuban detective TV program).

As to conclude, I will share an anecdote. I once heard Chavarria state he had written his novel X (I swear I don’t recall which one) because he was running short of money. I consider this is the best declaration of aesthetic principles by a National Literature Award: not to write for himself, or posterity, or the people (whatever that means), but for the only readers at his level: those who pay royalties.

Recommendation: If you are in possession of a book by one of these outstanding writers, get a specialist, study the market, get consultancy from a philologist;but just don’t let yourself go by the wolves in Wall Street.