Now spring really started in Madrid and “the faithful to the Alberti bookstore,” as Cuban writer Leonardo Padura affectionately calls them, arrived at number 57 Tutor Street, very close to the Moncloa metro station.

It is a narrow place, a kind of cavern bathed in led light and with multicolored book spines. The walking space is in an L shape and a pair of microphones and high stools for special guests have been placed at its vertex.

The space is so small that it is empty between books, shelves, posters and human beings, that for those of us who have arrived in advance, and before we all start to exhale in unison, the air begins to thin.

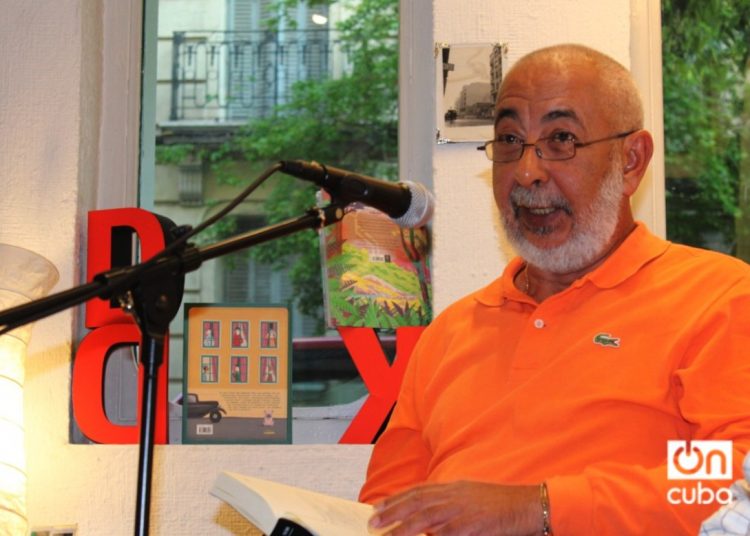

But at 7:30 in the evening, when it is still daylight, Padura and his wife, Lucía López Coll, arrive punctually. She is dressed very simple, all in black; I recognize her as Cuban because of her way of looking, how she tries to orient herself to look for a place to settle in the room. He comes dressed in orange. Not like I’ve seen him other times, in red or terracotta ―a gamut he seems to prefer― but orange, lively, sharp. Dressed in a Chemise Lacoste long sleeved pullover and a folded sweater over his forearm.

He is received by an uneven and immediate applause. He turns to the shorter side of the L, where some of us have sat on folding chairs placed there for the occasion. Padura waves in my direction. Of course it is not me who he sees. Among my neighbors there are many of his friends, as I perceive among those who respond with other greetings and other smiles. Many of them are, as I said, the faithful of the Alberti bookstore, people who have come here for the “umpteenth time” to listen to the presentations of the most prolific Cuban writer and one of the Cubans ever published the most in Spain.

Padura, who has been part of the catalog of the Barcelona Tusquets publishing house since 1996, is also an author with many followers in Madrid, where his book presentations have a safe home. Much more than in Havana, because of “the damn circumstance.”

Tusquets is turning 50, and this time it has commissioned editor Juan Cerezo to present the latest work of the journalist and narrator from Mantilla: a book of reflections on literature ―about his literature― that Padura has titled Agua por todas partes. Vivir y escribir en Cuba, retaking for himself the teleological definition of Cuban poet Virgilio Piñera in his “La isla en peso.”

The cover of the book refers us to the exercise of intimacy that the author presents us with in Agua por todas partes.

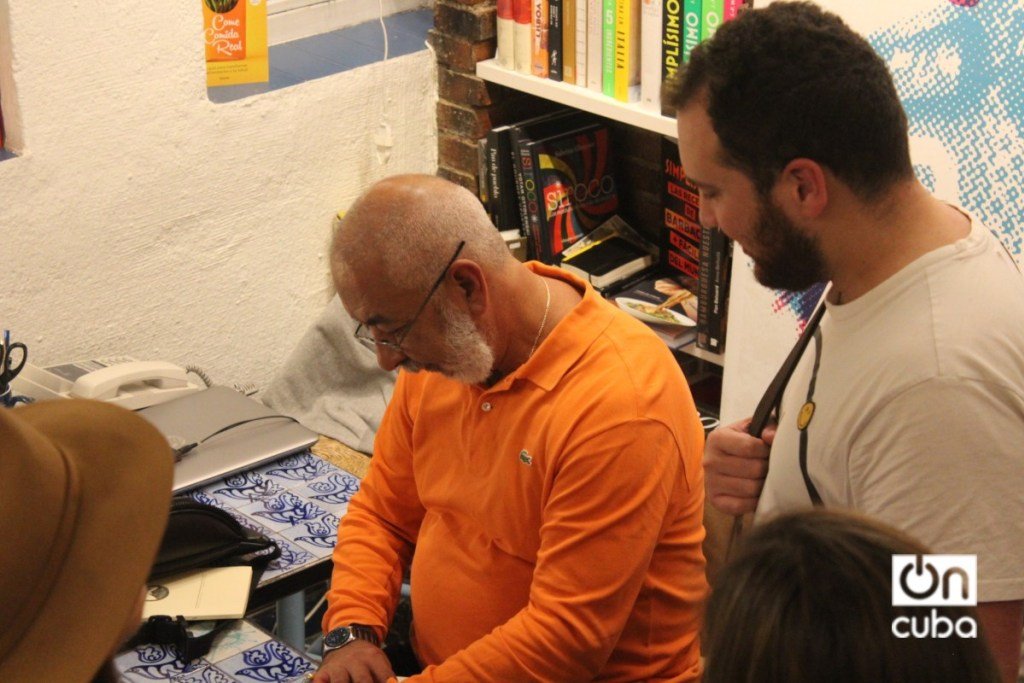

A very young Padura, five years old, in 1960 or 1961, holds a pen someone has placed in his right hand ―for the photo― perhaps to “correct” the southpaw inclination of this would-be baseball player, and who would sign his books in Madrid, as he has done for decades for his readers, with a very small writing that his left hand draws and in which a giant “P” stands out.

Agua por todas partes is a book of “literary secrets,” of comments, says Padura; a book that answers many questions that journalists and readers usually ask. “It’s a book to understand more who I am, what Cuba is, what it is to be a Cuban writer, and what it is to be a Cuban writer living in Cuba, who didn’t leave.”

“Why and for what does one write a novel?” is one of the central themes of this reunion of essays and testimonies that were written for about 20 years. Aguas…presents an author who deconstructs himself, thinks about himself, his creative exercise; who exposes the professional tasks of a writer and the ethical coordinates from where he performs the job of narrating. In the case of Padura, with the imperatives of someone who “works” fictional realities and characters that existed or that could have existed in completely plausible scenarios and situations.

“A writer is a warehouse of memories. One writes rummaging in one’s own memory and other people’s memories, acquired by the most diverse strategies of appropriation. Based on that the novelist creates a world,” writes Padura.

Havana is a major referent for him, but not in any way, but turned into his Havana, which “sounds like music and old cars, smells of gas and sea, and its color is blue.”

“My sense of belonging to Mantilla and Havana has made me the writer that I am and has induced me to write what I write,” he wrote in Aguas…

Padura said he sees himself as a “Stakhanovist” of literature: “I live writing, I live to write, it is my way of carrying out my daily life.”

While presenting Aguas… he announced that he has just finished the first version of a new novel that will recur in some way on the generational reflections of Regreso a Ítaca. The book will deal with “the exile dramas” especially based on stories of those who migrated in the 1990s.

“No exile is happy,” he said, because the act of migrating means, profoundly, renouncing all that is one’s own. And yet, identity is not abandoned, on the contrary. Padura recalled the Heredia of La novela de mi vida and how, from faraway, the exiled poet of the 19th century “achieved the first image of the Cuban homeland.”

In the next novel Padura promises to reflect on “the things that have happened to us.” He will especially focus on his generation: at 60 one is too young to die and too old to recycle, says common sense. His was a generation that dreamed of the future and had possibilities for their realization, but “they promised us more than they fulfilled,” he said.

“A Cuban writer with a minimum sense of his intellectual role and, above all, a citizen, is obliged to have some ideas about the island’s society, economy, politics (and, if he dares, to express them). In Cuba ivory towers don’t exist ―they have almost never existed―, for more than 50 years, politics has been lived as everyday life, as an exceptionality, as History being constructed and from which it’s impossible to escape.”

The afternoon drifted into new areas of inspiration for the writer. Great Cuban musicians like Bebo Valdés, Mario Bauzá, Chano Pozo, are “characters” about whom, he said, he would like to write a fiction novel.

He referred to Chano Pozo with special admiration and to the recently published book by Cuban researcher Rosa Marquetti, with whom he exchanged biographical information on these great names in Cuban music.

In Madrid, the last words of the writer, who although he has Spanish nationality said he is nothing more but Cuban, were dedicated to his inquiries into his Basque origins.

He has sought, he said, without success, the first Padura who went to America. A reader, also surnamed Padura, again came to the Alberti bookstore to hear him and without being able to hide a slight emotion, she sowed the desire to confirm their kinship.