The video of the song that gave title to the album recreated a pre-revolutionary club where Gloria Estefan sang with a retro orchestra. The musicians included Juanito Márquez, who made masterful arrangements for the album; bassist and mambo innovator Israel Cachao López; and a discovery by Estefan, Cuban-American singer Jon Secada (nephew of filin singer Moraima Secada), who had won a Grammy for the best Latin pop record. Mi Tierra got to be the number one Latin album in the United States, and remained as such for a year on the playlists. Since the days of the Mambo Kings, a recording of Cuban music had rarely appeared in such a list. Emilio compared the catchy sound of the album with the taste of “a combination of hamburgers with rice and beans.”

A few months before the debut of Mi Tierra, Albita Rodríguez, a young Cuban singer with a punk style and the voice of an old soul from Santiago de Cuba, crossed the Texas border from Mexico with her group’s musicians. They requested asylum and soon arrived in Miami, where they were welcomed by members of the Cuban community in exile. They recorded a jingle for a radio station, and in May they performed at a celebration for Cuban independence day at Bayfront Park in Miami. There, Willy Chirino, who at that time was the best-known Cuban artist in Miami after Gloria, also sang.

Gloria Estefan was the beloved icon of the emigres in Miami, their brightest star since she had become known as the voice of the Miami Sound Machine. Albita, who described her family in Cuba (his parents were also singers) as very, very revolutionary, imagined a future as an aircraft mechanic until her mother gave her a guitar when she turned 16. “It never crossed my mind that I would come to Miami,” Albita told me shortly after her arrival.

The release of Gloria’s album Mi Tierra and Albita’s arrival in Miami was a symbolic confluence, a prelude to the storm that was forming on each side of the Straits of Florida.

In the 1990s, Cuban-Americans in Miami came face-to-face with Cuba’s Cubans, seeing each other as in a distorted mirror in a fair. In Miami their cultures collided; both sides claimed the culture of that “land.” The music was a war cry in the cultural battles that culminated in bomb blasts, violent words and demonstrations. But also, as the decade passed, more and more frequently there were static concerts where musicians from the island played. For some of us, present among the public, those moving nights were celebrations of a new and incredible music. For others, they were, somehow, like coming home.

The Berman Amendment had come into force in 1988. This regulation was an amendment to the Trading with the Enemy Act, which applied the embargo against Cuba (the blockade). The Berman Amendment allowed Cuban musicians to legally give concerts in the United States, although always as a cultural exchange (that is, not for their work). As a result, Cuba’s first intrepid groups were well-received by curious and enthusiastic audiences in different cities of the country, but not in Miami.

Organizing a concert by Cuban musicians in Miami at that time required courage. Perhaps it seems difficult to believe now, but the people who tried to make history by presenting groups from the island did so by risking their money and being exposed to threats.

Bringing a Cuban group to Miami meant a considerable investment of time and funds. After the artists got permission from the Cuban government to leave the country, it was (and still is) the U.S. Department of State officials who decided whether a show was approved or not. The representatives of the U.S. government could wait until the last moment to deny a visa, without giving explanations. Many times, the decision to allow a concert depended on whether the artist or the situation in which he played could be considered insensitive to the feelings of the community of exiles, or possibly provoke demonstrations and/or violence.

It was a time when music mattered deeply to people who wanted to listen to the island’s musicians and to those who were not fans. Everyone considered that being able to play was a right, a sign of freedom of expression. It also mattered greatly to those who were clear that those “Castro agents” didn’t have to come to South Florida to exacerbate the pain of those who had been forced to leave the country after 1959.

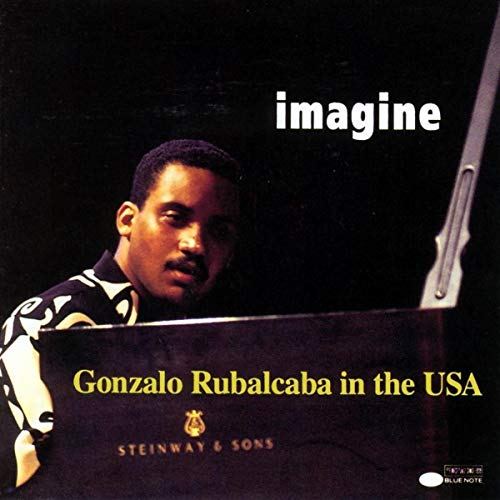

The Cuban musicians who arrived in Miami in the 1990s frequently became hate targets, scapegoats. And they ended up assuming the role of peace activists. In 1996 jazz pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba got a death threat before his concert at the Gusman Theater. He refused to cancel the show.

Alone on stage he played “Imagine,” by John Lennon, for members of the small audience who dared to go. They were spat on, hit with the masts of Cuban flags, and called “traitors,” “fagots,” “communists,” “whores” and “pigs” by the protesters waiting for them at the theater door. Rubalcaba, who a few years before had been chosen by Dizzy Gillespie to play at his side in Havana, and who had given concerts in places of international prestige, was called nigger. The important thing was to play, Rubalcaba said that night.

In Cuba, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the loss of its economic support to the dependent island, generated the so-called Special Period, driving hungry and desperate Cubans to try to cross the ocean in dangerous homemade rafts. The departure of the rafters reached its peak during the summer of 1994. A new wave of refugees arrived in Miami when the city was still recovering from the destruction of Hurricane Andrew in 1992. It was the third major immigration since the beginning of the 1960s.

The situation in Cuba led artists and intellectuals to leave the island. While timba music would emerge in Havana as the challenging soundtrack of changing and difficult times in Cuba, many musicians took advantage of a tour not to return.

A new class of Cubans raised and educated with the Revolution massively arrived in Miami. This time the newcomers could not be discarded as crazy and thieves, as during Mariel. In Cuba, the authorities were against the lyrics and way of dancing of popular artists. But already in the mid-1990s, the government gave some of them more freedom to go on tours abroad. They recognized that music was the perfect business card to seduce tourists, who were already key to the country’s economic survival.

In the United States, the Berman Amendment gave way to the entry of books, movies, magazines and―crucially―music, legally imported and sold in the country for the first time in almost 30 years. David Byrne, of Talking Heads, made his way to the archives of the Cuban label Egrem, taking out a series of compilations for his own Luaka Bop label, one of them titled Dancing with the Enemy. Thus he introduced American listeners to groups such as Los Van Van and Los Zafiros. Musician Ned Sublette founded Qbadisc, a label dedicated to Cuban music in New York, and which since the beginning of the 1990s released albums by NG La Banda, Carlos Varela and Los Muñequitos de Matanzas, as well as other artists that were heard in Cuba.

In the Miami of the 1990s, listening to CDs of contemporary Cuban music still felt like something exotic and even subversive. For some time, you could find the largest selection of recordings made in Cuba at the offices of Marazul Travel, a pioneer agency for traveling to Cuba. There, in 1996, an explosive device went off, an act of protest against the Miami-Havana charter aircraft business. The curator of that selection of albums was Emilio Vandanedes, a music lover and Cuban DJ who had been Rubalcaba’s bodyguard during his concert at the Gusman Theater. Emilio, my friend and a great source of information, died suddenly of an illness in 1998 shortly after seeing Francisco Fellove perform at an outdoor festival.

In 1997, telephone death threats were received at the WRTO-FM station, when songs of contemporary Cuban musicians started being played. Immediately after that the station stopped playing them.

There had always been an underground flow of Cuban music in Miami, mixtapes of cassettes were exchanged between friends, for whom the music of bands like Los Van Van, Irakere or NG La Banda was the sound of their youth and their homeland. But it was already easy to buy albums made in Cuba in stores like Esperanto Music, in Miami Beach; and even in the iconic Do-Re-Mi in Little Havana.

For young Cuban-Americans, being able to hear the island’s current sounds meant that Cuban music could be more than the soundtrack of the memories of their parents or grandparents, more than their chimeras and their “remember when?” For many of them, getting that music was like finding a message in a bottle, discovering a real Cuba. Music was a link to their roots, an emotional call to action. Before the end of the decade, many from that generation would go to Cuba to see it with their own eyes.

Of course, Cuban music itself was not a new thing in Miami, but it could be complicated to find it (a paradox difficult to understand for someone coming from abroad expecting to listen to Cuban music at all times). In the 1980s the cultural image of the city was painted by the pastel landscapes and the track music from Miami Vice; the owners of the local clubs wanted disco music and DJs, not Cuban orchestras considered more expensive and démodé.

Cuban musicians came to Miami for decades, some attracted by the weather, others because it was a place to live among Cubans, and others because they thought they were going to find a vital live music scene. Many found jobs as sidemen in recording studios, performed at weddings, sweet-15 parties and bar-mitzvahs, where you could earn quite a bit; or they went on tours outside of Florida.

The rainy night that I met pianist Paquito Hechavarría, in 1997, he was arguing about money with the owner of a restaurant in Coral Gables, where he played some nights at dinner time. “Obviously, he doesn’t know who Paquito Hechavarría is,” he complained angrily, after the restaurateur showed him the door.

But there weren’t many people in Miami who would recognize him. In Havana, Hechavarría had played with the Casino Ensemble and the Riverside Orchestra. When he arrived in Miami in the early 1960s, he was hired by the Fontainebleau Hotel, where he accompanied Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, among other stars. He went to Las Vegas and then returned, forming the Wal-Pa-Ta-Ca group with Cachao, Walfredo de los Reyes and Tany Gil. His idea of being a hit with a new Cuban sound did not work. For the Miami audience, the most recognized Hechavarría music would always be the Miami Sound Machine’s introduction of “Conga.”

Former Los Van Van singer Israel Kantor Sardiñas stayed in Mexico during a tour of the band 1983. He explained that from there, personal circumstances brought him to Miami. “Miami never interested me,” he said, although he was still there when we met almost 15 years later. “I had no idea what Miami was like and it didn’t matter.”

In the 1990s, that exceptional son musician was singing merengue and salsa in a shabby club, trying to satisfy an audience made up of new immigrants from Central America. For Kantor, Miami was a kind of purgatory. Although he was still making records and looking for a new beginning, he told me that he longed for his years with Los Van Van, which he described as the best of his life. He died of cancer in 2006.

There were always people who refused to accept the lack of a live Cuban music market in Miami. In 1990 the promoter Arturo Campa organized the “Reunion of the Masters,” with a cartel that included José Fajardo, Cachao, Alfredo Chocolate Armenteros, Hechavarría and José Chombo Silva.

In 1992 actor Andy García marked a milestone in the reaffirmation of Cuban musicians who had been ignored for many years in Miami. He put his idol Cachao as the central figure of a concert that was filmed for a documentary released in 1993. In 1995 his return album Master Sessions Vol. I won a Grammy. Cachao was 76 years old.

South Beach, then, was experiencing its own renaissance in the early 1990s. The new destination in fashion also offered a warm atmosphere for a new appreciation of Cuban music. The audiences were diverse, and the concerts were often organized by people who were not Cuban. The Rhythm Foundation introduced Mario Bauza in 1991 at the Cameo Theater, and again at the Stephen Talkhouse club in 1993. Conga musician Patato Valdés and Cachao also played that year as part of the Latin Meets Jazz on South Beach series.

The music of Nil Lara, a Cuban-American who played the tres and was a fan of Pink Floyd, sounded frequently in the Talkhouse with a group that included Albert Sterling Menéndez (son of guitarist Alberto Menéndez) and percussionist Florencio Baró, who worked in a bakery near Lara’s apartment.

Albita and her group gave their first concert in Miami at the Talkhouse, before starting regular shows at the Yuca Restaurant in Coral Gables and the Centro Vasco on Calle Ocho, where many Cuban-Americans had the first opportunity to listen to artists who had come directly from Cuba. Madonna was also a fan. After Albita was approved by the public, Emilio Estefan signed her for his label, Crescent Moon; he gave her a glamorous makeover and a more sophisticated sound. For Albita, a sense of cultural shock grew along with her fame.

“I’m a hot potato,” she told the New York Times at the time. “First they questioned my political positions, and now my artistic talent. First they said I was still a communist, and now that maybe I sold out. That is a lot of interpretation of someone new who arrived from the other side.”

Her confusion and frustration led her to write a very personal song, while summarizing the sorrows and glories of the universal Cuban experience: “Qué culpa tengo yo” (It’s not my fault that I was born in Cuba).

In 1995, the former director of the Havana Film Festival, Pepe Horta, together with a friend, opened the Café Nostalgia, a club where the Cuba of the present and the past came together.

“I invented Café Nostalgia so as not to feel nostalgic,” Horta told me. As a result, a place was born where anyone who wanted to listen to some live Cuban music had somewhere to go. The house band, Grupo Nostalgia, was mostly composed of young and newcomer musicians. They were gradually introducing what for Miami was a new sound.

“At the beginning we played the songs in a more traditional way, like the old bands,” said Omar Hernández, who was leading the band. Formerly a bass player with Afrocuba and Cuarto Espacio, Hernández arrived in Miami in 1994. “Later, little by little we got people used to the sound of more contemporary Cuban music.”

For many it was pure magic. The existence of the club was an open secret that spread rapidly. Matt Dillon and Marc Anthony passed by when they were in Miami. It wasn’t about politics. The club’s message was rather one of music and camaraderie. But often members of a minority stood across the street to protest the existence of what they considered was a “communist club.”

They took pictures of people entering, “an act of repudiation” that seemed surreal. But the party continued. The club changed owners in 1999 and became Hoy Como Ayer, where live Cuban music performances continued until it closed in June 2019. “The only way to annihilate nostalgia is to recreate it and turn it into something else,” Horta told me. “We have turned nostalgia into a creative activity. We live the past, we remake it and create the future.”

In 1996 someone threw a Molotov cocktail through the window of the Centro Vasco Restaurant on Calle Ocho to protest a concert by singer Rosita Fornés, who was still living in Cuba. The show didn’t take place, and shortly after the Centro Vasco, a Cuban emigre institution, a recreation of the restaurant that the Saizarbitoria family had in Havana, closed its doors. That same year, a concert by the Aragón Orchestra was canceled after the promoter received telephone threats.

In March 1998, folk-rock singer-songwriter Carlos Varela performed for a small audience as part of an acoustic showcase organized by Warner Chappell publishing house in the lobby of a South Beach hotel. Varela’s performance electrified the night, demonstrating that there was nowhere outside of Cuba where his poetic protest songs could have more impact than in Miami itself.

A month later, at a concert promoted by “Radio Bemba” (word of mouth), Issac Delgado sang for a thousand people at a disco in South Beach. The historic moment finally came in June, when the Vocal Sampling group performed at the Lincoln Theater in Miami Beach. It was the first concert in Miami endorsed by the U.S. State Department in 35 years.

When the album Buena Vista Social Club came out in 1997 it was an amazing international hit. Then it became a veritable phenomenon. The reactions to the album produced by American Ry Cooder were generally less enthusiastic in Cuba. “The product of BSC, in any of its versions, is so genuine that it cannot be misrepresented, even though, among other lies, there are those who try to present this case as a mere nostalgic postcard―the most innocent expression―or as if in the last 40 years―and now comes the deceitfulness―music on the Island would have stopped and that is why we must look at the supposed pre-revolutionary eternal Cuba,” wrote Pedro de la Hoz in Granma in 2000, after the premiere of the documentary Buena Vista, directed by Wim Wenders.

Paradoxically, in Miami some in the exile community had their own objections to that homage to pre-revolutionary music because the participants lived in Cuba. Compay Segundo, the nonagenarian star of Buena Vista, was invited to perform at the Miami Beach Convention Center in August 1998 as part of the MIDEM Latino conference (the “Cuban Legends” concert also featured Chucho Valdés and Irakere, Omara Portuondo and the Charanga Rubalcaba).

A year earlier, MIDEM had canceled its plans to include Cuban artists in the event, under threat from the Miami government. Specifically, a local ordinance (enacted in 1996) that prohibited any entity that does business with Cuba or does business with a third party that does business with Cuba, to be included in a state contract with Miami. Those from MIDEM would have to sign a so-called “Cuban Affidavit” that essentially prohibited performances by Cuban artists at the conference. However, this regulation disagreed with U.S. policy, which did allow concerts by Cuban musicians within its cultural exchange program.

For the 1998 edition, MIDEM produced the event with private funds, without the local government as a sponsor, being free to schedule the concerts as it pleased. But not everyone in Miami was in agreement.

The performance of the charismatic Segundo was interrupted by a telephone bomb threat. Spectators left and police dogs entered to sniff the room and stage. Nothing was found. “Well, then they had their rest,” Segundo said as he sat in his chair with his guitar. “Music is music!” he shouted with gusto. “Music doesn’t bother anyone.”

“I really don’t know anything about politics,” he had told a group of journalists before the concert. “I’m not anti-anyone. Living bitterly makes life bitter. Life is not for being bitter. Life is to enjoy it, to look at the landscape and beautiful women. That is man’s life on this earth. A person who spends his time doing something else, okay. They’re not going to have much fun.”

In 1998, Cuban artists continued to arrive in Miami, most of them with no incidents. The audiences grew and the concerts of musicians from Cuba were already seen, almost, as normal. It was a year of rupture, no doubt. But it was also the calm before the storm, that of Hurricane Van Van.

Debbie Ohanian, the owner of Starfish, a South Beach club known for its casino dance classes, announced that at last she was going to bring Los Van Van to Miami. The reaction in the local Hispanic radio came quickly. Armando Pérez-Roura, from Radio Mambí, encouraged listeners to call his show to insult the band: “dogs,” “trash,” “killers.” Miami Mayor Joe Carollo, who publicly baptized Ohanian with the nickname “Havana Debbie,” also appeared on that show, among others, to stoke the hate. Even musician Arturo Sandoval, who arrived in 1990, called the show to say he had nothing to do with Los Van Van. After a series of twists and turns worthy of a thriller, the concert was confirmed for October 9, 1999 at the Miami Arena.

The night of the concert, police officers on horseback with helmets and shields were stationed between the doors and about 3,500 protesters, according to the police; a number somewhat larger than the people inside. Some who saw the concert had entered wearing masks so as not to be recognized by family members or their co-workers. Others turned around at the door before entering to greet the people shouting below, who carried signs with phrases like “communist beggars.”

The group started the concert with “Ya empezó la fiesta.” “Salsa for you!” shouted singer Mayito. “And from Cuba!”

After the concert, Miami government officials sent a bill of $36,000 to Ohanian, forcing her to pay extraordinary security costs. She paid, and then sued the city.

The ordinance―the so-called Cuban affidavit―that had locally censored Cuban artists, ended in 2000, when a federal judge declared that it was a violation of the first amendment of the United States, which guarantees freedom of expression.

In 2003 Debbie Ohanian won her trial against the city. She received a total of some $90,000, counting the interests and what she paid her lawyers.

The 1999 concert is preserved in a two-disc boxset, Los Van Van at Miami Arena.

https://youtu.be/v1cNq-pf9n4

*This text was originally published on Radio Gladys Palmera. It is reproduced by OnCuba with the express authorization of its editors.