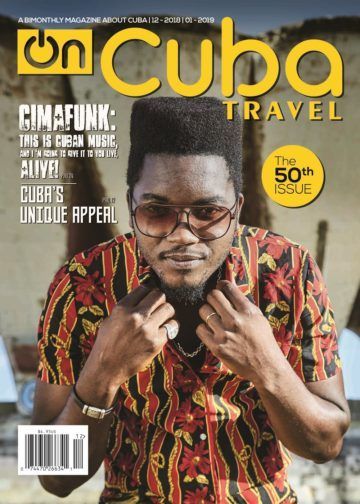

Cima

My old friends call me El Manta. They’re friends from when I started with trova, and my buddies from high school, when I did a bit of reggaeton. I used to talk a lot. I used to distract the teachers so we wouldn’t have to do what we were supposed to. That’s why they gave me that nickname. But now I’m Cimafunk.1 Or Cima. Or Erick, sometimes.

I have a favorite bolero. It’s “Debí llorar”, sung by Freddy [2]. I really like it a lot. I don’t watch sports, although I did pretend I was an athlete. I practiced track and field, Greco-Roman wrestling, and boxing. My mother told me that I had to study first and afterwards I could do what I wanted.

It’s true what the song “La sandunguita”[3] says, “no one can take away what you’ve been given,” but watch out: you have to see what sandunga was given and by whom. I studied Medicine for a few years, and I gave it up for Music.

I sing to happiness. To a state of mental happiness, in which people can enjoy my music. And listen to it doing whatever. What each person decides to do with my music is their problem. If they’re dancing, or if they’re cooking. My intention is to make people feel good, for them to enjoy themselves.

I’m afraid of anything that isn’t doing what I like and that prevents me from taking the time to do what I like. I’ve done a lot of things in order to eat and make a living. I don’t mean only music – I’ve also done manual labor. I wouldn’t kill anybody over a piece of bread. There are always other ways to do things.

To my “patients”[4] I prescribe systematic doctor’s visits. My therapy depends on the person’s illness. They are offered specialized therapy. There’s something for everyone: there are vegetables and there are sausages. It depends on the illness. What’s wrong with the black man? And you’re asking me? Well, you’ll have to ask her. She’s the one who pretends she doesn’t know, but she keeps appearing.

Racism, awareness

I like to talk about my grandmother. Usually I’m not asked about her. My grandmother, and I still feel it like that, she’s here, with me. She’s like a futurist lighthouse. Things happen to me which she had already told me would happen to me. I get supposedly new information, but which she had already given me.

My grandmother educated me in a very traditional way. With a great deal of love, and with norms of respect and education at home; she was very serious about that. She suffered from racism when she was a child. She lived in an isolated part of the countryside and experienced racial differentiation. There was a barrier in that town (in the province of Pinar del Río): “colored people here and whites over there.” She always had that trauma. She made the greatest effort so that all her children would go to school. I have an aunt who’s a surgeon, an uncle is an engineer, another aunt works in public health. They all went to university. Some neighbors used to say to that aunt of mine, the surgeon: “when have you seen a black woman studying to be a doctor?” All the education my family received was based on improving themselves and studying. And in subtle, respectful communication.

I’ll be sincere with you, my sensitivity about racism happened through history rather than having lived it. My family took up almost a quarter of the block. Three of my great-uncles lived there, each one with his children. Some of the great-uncles’ children had left, but others continued there. One of my great-uncles had a carpentry shop. My uncles lived in my grandfather’s house, my entire family.

My family always deserved respect. It was, and is, a beloved family. My grandmother passed away, but my great-aunts who are alive are people who are as respected and beloved as she was. Everybody goes there all the time. I remember how the people used to go to talk to my grandmother. Everyone knew her. We were very well-educated children. If grownups were ever visiting at home, we never came in through the living room, we used to go around to enter. We never interrupted the grownups’ conversations.

I’m talking about the countryside, which at times is a bit more conservative in its way of thinking. Of course, there were manifestations of racism, but as a child I didn’t experience them. What I got was something else: “those people are very educated. They are blacks who have gone to school. They are intelligent blacks.”

By saying that, now you know there’s something behind it. When you’re older you start analyzing and you see that where we lived there were only two black families. Racism was lived like something cultural. What there is of racism in Cuba’s rural zones is some type of “segregation” between whites and blacks, but as a long-time form of culture.

Until now, what I have left was the history my grandmother lived, what she used to tell me about it. Her conception. I notice it more now when I think about how she used to say that “in this house you can’t speak loudly so that the whites don’t say that these blacks are noisy and loudmouthed.” She was referring to the white neighbors next door. That conception started entering my head. There was real suffering. She lived it and carried it inside her. Her conception helped her to transform the experience to help us. It transmitted her feelings.

Most of my friends were white. That’s normal. I never felt uncomfortable with that. It was up to me to always see the positive. To assume it as identity. It’s good to know what happened. It’s good to know history, especially the history of my people. When you know it, you are more aware. I know there are cases and such, and there comes a time when you have an awareness of your conviction, of your right as a human being.

The market: croquettes and what’s hot

Many people make a single and try to sell it. Then they make another and another, and when they have several, if they work, they make a record and sell it as such. The issue is that the record as a product has lost value. Internet has been fundamental in this transformation. It has made the market function differently.

I came to the conclusion that I’m not interested in genres. I don’t want to make a funk or a rumba record. I want to make a record of songs I like, no matter what genre they are. I put them together and give them to people. “Parar el tiempo,” a funk-record-ballad, is on it. There is “Me voy,” inspired by Nigerian Afro pop, with a conga and a Cuban tres tumba’o rhythm, or “Ponte pa’ lo tuyo,” which is funk with cha-cha. If you trust in what you’re doing, you can do whatever you want with your music. That way the relationship with the market is more flexible. If you’re doing a good job, they can tell you “I want all of it.” That’s awesome.

Perhaps things were different before. They would put you in a “small box” according to the genre, and that’s how you circulated. There was the small box of the blues, the small box of pop rock, that of funk, and so on. It was necessary to be put inside a small box. I feel that now it’s different. Once again: Internet deeply changed this situation. In fact, up until now, I’m only distributing through the digital platforms.

I don’t compare myself to James Brown. If I were at that level, I would be in another dimension. I just recycle music made by that genius and others like him. I’m cutting and pasting, and putting in a bit of myself. I didn’t know that Leo Brouwer once said: “tradition can be broken, but it takes a lot of work.” Just imagine. Appropriating a tradition is always recycling. But I look for the originals, not those who have recycled the originals.

I sit in front of the computer and I start working the themes. However, it’s not until the end, until I play it live, that I see how it’s going to turn out. I have to set it up with the band to play it live. To set it up with the band I have to hear what the musicians tell me. I always listen when they say “this is what it is.” And I tell them: “if you don’t like what I put there, do it better.”

In my live performances no song sounds the same as on the record. The bass player and the guitarist don’t play the same as what is recorded. The drummer even less so. Everybody is doing their part. In the end, it’s not only my responsibility. We are collaborating. I’m not afraid, I like the way we do it. It gives me confidence. I feel satisfied with the song when I know that I like it. That’s when I feel I can defend it. That’s when the song becomes real.

The music market is like everything in life. If you make different varieties of bread, you take it to the industry, you industrialize it, you create a transnational and start to make millions of tons of bread a day, the quality won’t be the same. That is clear. Quality and quantity always get into a jam.

Today the market is everywhere. Everything is sold. The video clip, the background, singing a cappella, the artist’s sneakers…. It’s madness, but it is part of this field’s evolution. It’s something you have to work with. In the end, it’s a business.

In several senses, the way the music market is evolving is also the way in which human beings are evolving. We are evolving toward overcrowding, overproduction, and toward always trying to have more, more, more. However, the issue is that even in the market there are things that go with you, that you like, that are really great. Now people have more access to listen, to choose a greater variety of the music they like. You have to know where to find it.

I like what Brown or Prince did more than what Michael Jackson did, I’m a great fan of Brown. And I adore Michael, but James, or Prince have got something. It’s what they did live what resonates with me. It’s a different attitude. A sort of possession. Beyond the groove, Brown didn’t mind spending 20 minutes on a song, shouting, moving, completely possessed.

Brown made a name for himself, he made his money, but he didn’t get into the market in the way pop did. Michael is pop. And this is something that’s massive, a music with its set parameters, which you have to respect, because it demands that many people understand it and can follow it. That’s why I always liked James more. As a musician I feel more identified with that style, with that freedom, with that freedom when performing live, with the freedom when it comes to writing. I spend a really long time writing a song.

https://youtu.be/1UzZUfFUnxY

These days reaching an audience doesn’t even depend on your music. It depends on having contacts and how much you can influence people, on the marketing company you rely on, on the level of people around you. Everything involves the management of information. You can give people croquettes, and people don’t like croquettes, but you put croquettes on a sign every day and people end up eating croquettes.

However, I do want to reach millions of people. I want to reach as many as I can. That’s normal. But I want to do it by doing what I like. I want to live as I live, and give it to them my way. I’m doing what I like. There’s not necessarily a problem between the two things. In the market there’s space for many things. I won’t let what Fito Páez5 told me go to my head... I tell myself, “it’s normal, veo [buddy],” but it’s great that he said that.

Cuba

About Cuba I’m proud of the people, of everybody, bro. I’m in love, with all my heart, with Cuba. In France, and everywhere, everything is great, but there comes a time in which I need to return, to be at home, with all my craziness. I’m a fan of that, because it feeds me. It feeds me a lot.

The same people are also what makes me sad about Cuba. All of a sudden things start happening among Cubans, and things that didn’t used to happen do, in the way we treat each other, for example, not helping each other. When you go to Pinar del Río, to a town in the countryside, you knock on a door and it opens and they offer you lunch, they give you food and they ask you what you need. That is the feeling you find. When I came to Havana it was shocking. Everything was colder. When you go to other countries, you realize that it’s even more extreme. I don’t like it when I see people start to change. That is like seeking your loneliness inside yourself. You can have 20 million dollars and if you can’t share them it’s no good. It’s all in the people, bro.

I respect everything that has to do with religion. Some time ago I was into Christianity. But for me the concept of religion is divisive. It creates drama, it’s like making a movie. On occasions, it becomes a business. Many people are in it to see who offers the most. As a business it is lethal. I prefer to stay close to the spirit of religion, but not of the institution created on its behalf. But well, I know that the energy is there. It’s there.

I disagree with certain things that are done in the name of religion, like being opposed to marriage between two people of the same sex. I can’t tell anybody what they can or can’t do. Let everyone do what they want with their body. For me, that opposition is an invasion of others’ freedom.

Afro-Cuban? Cuba’s music

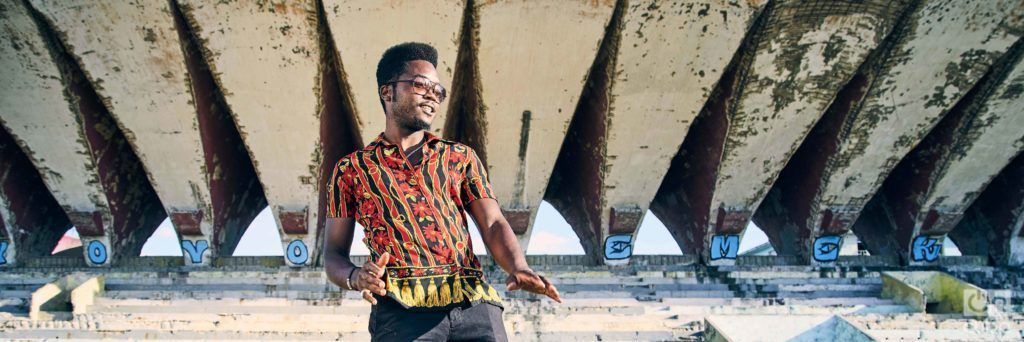

When you hear the song “Me voy,” what we do, how we sound, especially in the live shows, you can get an idea of why I call what I do Afro-Cuban funk.

During the process of slavery, African cultures were brought to Cuba and they experienced many transformations. They were mixed among themselves and with many other things. But now I’m using resources that were not transformed here, like a type of clave used today in Africa, for example, by Fela Kuti. I’m talking about native resources. I use them like they use them over there. Sometimes I mix them more, or less, but I’m working on resources used in present-day Africa.

I started making the record Terapia in France. There, and in Europe in general, people get a kick out of the Afro beat. In that context, “Me voy” started emerging. The idea of the song is that it be a more Afro beat. But the Cubanness came out in the mixing. And I told myself: “Well, this is what it is.” I don’t understand anything about being pure. Everything is a mixture. You shouldn’t be afraid of mixtures. Well, everyone is afraid of what they’re afraid of, but that’s not my case. I’m studying what has changed in Cuba, what hasn’t changed, or what has changed less. There are many similarities, but when you listen carefully, you can see the differences that are preserved in the mixes.

However, I always have a hard time defining where this or that comes from. If I play it and it works for me, I use it. Perhaps there are exceptions, like some classical music, but I’m not even very sure of that. Everything came from somewhere and started to spread. Specially in Cuba, where we have an incredible transculturation.

We have an extraordinary amount of genres, of music styles, an incredible amount of ways of playing and singing. Cuban music is very complex, because it contains a great deal of information. You see that when you show Cuban music to other musicians in the world and they always tell you something like: “this is very complicated.”

Many people stay on the surface, playing the son, the clave, but, bro, from here to there, the Cuban son is madness. You start looking around and what came from Africa and remained in our conscience is negritude, the underground, but it has an enormous amount of rhythms. Arsenio Rodríguez is an example. What he did was madness. What El Guayabero did was madness. And Benny [Moré], please. And then you jump to Freddy and you see that it’s something else, and you say to yourself “but what the hell is she?” She’s like a black version of Edith Piaf.

Cuban music enforced itself on America and Europe. I’m making Cuban music. And I’m going to give it to you live. Alive, damn it.

Foot Notes

Cima, from cimarrón (a black slave who runs away in search of freedom) and funk (musical genre born in the 1960s when musicians, mainly Afro-Americans, fused soul, jazz, and Latin rhythms.

2 Freddy, or La Gorda Freddy, was the artistic pseudonym of Cuban singer Fredesvinda García Valdés (Camagüey, Cuba, 1935-San Juan, Puerto Rico, July 31, 1961). Some called her “the Cuban Ella Fitzgerald.” Guillermo Cabrera Infante immortalized her as one of the characters in the novel Tres tristes tigres. Despite her short artistic career, with an impressive voice and presence, she left an imprint on the interpretation of bolero and son in Cuba.

3 Song performed by Cuban musician Isaac Delgado, composed by Alain Pérez.

4 The song “Paciente,” by Cimafunk, is included in his first “solo” album Terapia, 2017.

5 At the closing ceremony of the Gibara Non-Profit Film Festival (Cuba, 2018), the great Argentinean musician Fito Paez invited Cimafunk to sing with him the iconic “Yo vengo a ofrecer mi corazón,” and he said: “I want to invite up this black American God, perhaps one of the future’s brightest lights in the continent, his art impacts me.”

This interview is part of OnCuba Travel Magazine 5oth Edition