In 1946 a Santiago-born graduate of Business Administration at Yale University called Goar Mestre (1912-1994) laid the first stone of a building on the corner of 23 and L. Then he said something that worked like an oracle: that this would be “the heart of Havana.”

It was the birth of a cultural and business complex designed after New York’s famous Radio City, and in particular the Warner movie theater―Radio Centro and finally Yara would come later―with capacity for 1,700 people, in which the first film in Cinerama, a technology released in the United States in 1952, would be shown.

And it was also the birth of those five blocks from 23 and L downward, in search of the sea, which would be known as La Rampa.

At a short distance from that heart, on 17 and N, the Focsa building (1956), by Ernesto Gómez Sampera, was the pioneer of coastline skyscrapers, one of the seven wonders of local architecture. Then came the Capri Hotel (1957) by José Canaves; and on La Rampa the Retiro Médico (1958) by Quintana, Beale, Rubio and Pérez Beato; and the Habana Hilton (1958), a run-on of Welton Becket Associates with the Cuban Arroyo y Menéndez firm, an unparalleled monumental work in Latin America at the time.

On 23 and O the urban planners set up another movie theater, designed by Cuban architect Gustavo Botet, initially a Boleras Tony bowling alley, but readapted in a short time for its other use, where in 1957 the Todd-AO system was made known in Cuba, made to compete with Cinerama, with the exhibition of Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and the performances of David Niven and Mario Moreno (Cantinflas).

Banks, restaurants, airline agencies and offices reinforced the cosmopolitan character of the area, and by extension, of Havana itself. On O Street, passing through Monseigneur Restaurant and crossing 23rd Street, three hotels were built, one after another: Saint John’s, Vedado and Flamingo, very close to the Montmartre Cabaret on Humboldt and P.

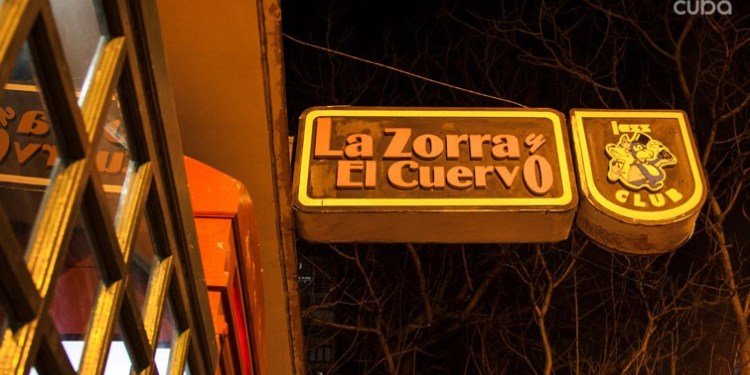

Also, it certainly was the time of nightclubs along those very famous blocks. Suddenly more lights appeared in the city trying to compete with El Prado: Olokku (23 and N), La Zorra y el Cuervo (23 and O), La Gruta (23 and O)…, escorted by others in the very Vedado and in Miramar: Club 21 (21 and N), Karachi (17 and K), La Red (19 and L), El Escondite de Hernando (Infanta and P), El Gato Tuerto (19 and O), El Scherezada (19 and M), the Turf (Calzada and F), the Johnny’s Dream, on the other side of the Fifth Avenue tunnel, next to the Almendares River.

Oh, La Rampa. Oh, Havana.

A few years later, the 7th Congress of the International Union of Architects was held in Havana in October 1963, an event that brought together more than 2,000 professionals to discuss the architectural problems of the Third World. There they agreed and took action to continue with La Rampa’s modernity. It was then that it was decided to build the Cuba Pavilion and the 23rd and Malecón waterfall.

There the idea also emerged of doing something distinct and different with those five blocks’ sidewalks: to include mosaics by Cuban artists such as Wifredo Lam, René Portocarrero, Hugo Consuegra, Mariano Rodríguez, Amelia Peláez, Cundo Bermúdez and others. An open-air art gallery along which people could walk. The most renowned architects, engineers and plastic artists were involved in the project under the direction of architects Fernando Salinas and Eduardo Rodríguez.

The recently repaired ice cream parlor, Coppelia, would end the process in 1966.

Along with La Rampa, what would become a tradition among generations of Havanans was inaugurated: walking up and down La Rampa. Isabel Rigol and Ángela Rojas wrote:

“In this area you could walk, eat in a good Chinese, Polynesian, French or Cuban restaurant; have a snack in a New York-style cafeteria. The night owls could drink and dance in the basements skillfully adapted for cabarets, hear the best of filin, buy exotic objects in the Indochina store located on the ground floor of the Retiro Médico, buy fine porcelain or Danish glassware in the Casa Dinamarca, buy books that were in fashion. One could also attend the performance of the excellent Spanish musical groups that passed through Cuba, such as Los Chavales, Los Xeys and Los Bocheros, or Italian singers Ernesto Bonino and Tina de Mola, who performed at Radio Centro. You could, at any time, walk up and down La Rampa.”

And in 1964 Mario Trejo proclaimed the following from the pages of the magazine Cuba: “La Rampa is not a street. La Rampa is a state of mind…. The urban planning experts define La Rampa as follows: the stretch of 23rd Street, in El Vedado, which for ten years has become Havanans’ favorite place for a stroll.”

In June 2019 the Electric Company decided to form part of that history in a peculiar way: breaking and cementing a part of that sidewalk, the one on 23 between L and M, with the subsequent destruction of that granite structure fused in the Ornacen S.A. workshops, Rancho Boyeros, in 1963.

https://www.facebook.com/ulises.toirac/posts/2625914447442803

A complete mess. And an action sustained, to say the least, on an overwhelming mixture of ignorance, irresponsibility and apathy. But that is not the biggest problem. Nobody intervened. Nobody ordered it to stop. And nobody rendered account, even this act of cultural cannibalism was denounced both inside and outside the island.

Artists and intellectuals. Common Cubans and others with a different frame of mind in social networks. Press organs on the web. The Cuban ambassador in Austria said on Twitter: “This is not the Havana we deserve. This is called indolent chaos.” And also: “Attention authorities of my Havana. It’s La Rampa. It’s a heritage sidewalk.”