The first thing spectators see when they go to see Sergio and Sergei (2017) is a screen that reads: Mediapro. Further on, RTV Comercial comes on.

The first is, according to the firm’s page, “a leading group in the European audiovisual sector, the only one in the integration of audiovisual contents, production and distribution.” The second, the marketing enterprise of Cuban radio and television, which in recent years has been increasingly dedicating itself to the production of its own contents instead of only operating as a seller for the rest of the national entities. Both, together with institutions like ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinema Arts and Industry), are the producers of Ernesto Daranas’ new film.

The previous detail does not suppose a prejudice. That Sergio and Sergei is a fruit of the contemporary cultural industry is barely a data. There is no problem in that, or with the marketing logic associated to a cultural product. Neither is this the case with the idea of a Cuban movie that originates (as most Cuban cinema since a while back) in the combination of transnational financial sources. The problem appears when this has an incidence on the resulting text. And it’s not for the better.

Daranas’ new film is again, according to what its director tends to say, genre cinema with a social background. In Los dioses rotos (2008) it was the melodrama and the detective; in Conducta (2014), melodrama; now the dramatic comedy.

The anecdote of Sergio and Sergei follows a young Cuban professor of Marxism trapped by the fall of the European socialist bloc right from the start of the 1990s and during the beginning of that, which we Cubans know as Special Period in Times of Peace. Sergio sees how the absolute truths of his philosophical system are submitted to questionings, while the need for survival forces him to reinvent himself, to curb his perception of the reality that obeyed almost finished categories.

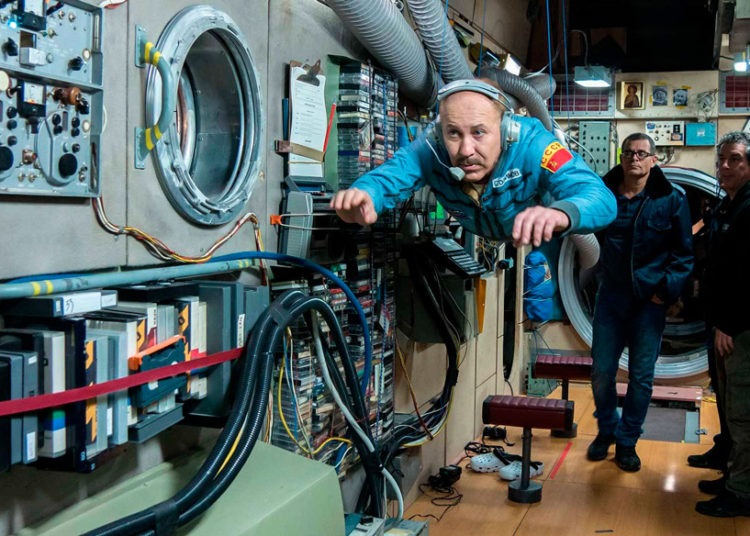

Sergio is also a radio ham. Someone who has a communication terminal with the exterior world. Through it he establishes contact with Sergei, a Soviet cosmonaut adrift in the MIR orbital station after the sudden disappearance of the USSR and of the public institution in charge of his sustenance and return.

Sergio and his radio telecommunication apparatus are going to play a fundamental role in the rescue of Sergei and his return to Earth safe and sound.

Sergio and Sergei is a film about solidarity and survival (although its director describes it as “about friendship beyond cultural, geographical and political borders”), with the background of the Cuban national plot. Those ingredients supposed, from the very plot, a bridge between plots and diverse incidents, which had to be managed with wisdom and courage.

But it is also a film about vigilance. And here is where the comedy part of the story appears.

Having a privileged access to individuals and information from the “exterior world,” Sergio is watched and his activity is closely supervised by a police system that receives special attention in the film’s dramatic system.

There is a serious problem with the representation of the power subjects in Cuban cinema; it is difficult to find a solid realistic writing about them, which turns them into credible antagonists (as is always the case in Cuban cinema) from the dramatic viewpoint. The common solutions are to draw them through the outline of unidimensional, stiff and solemn characters or, as is the case of Sergio and Sergei, in a comedy key.

Some positions that challenge Cuban cinema in its critical aspect of social reality have used this to accuse it of manipulator, as if dealing poorly with the real phenomenon were enough to say that that phenomenon exists just in the bad intention of the creators. There are examples of both treatments in the Tomás Gutiérrez Alea of the end (Guantanamera, in comedy key) as well as in the vilified Santa y Andrés (in dramatic key with tragic tones) by Carlos Lechuga.

The police officers are the most maladjusted in the structure of the characters of Sergio and Sergei. The character of Yuliet Cruz, who plays the higher officer who attends to Sergio, and that of Mario Guerra, the security guy by antonomasia, represent the double vertex of the characterization I previously described. The first is always constrained, in its role of severe and authoritarian boss, while the second incarnates the not very important vigilante, chasing after all types of proofs, which allows him to climb or to at least be recognized by his superiors; thus he’s always suspecting and seeking evidence where there is none.

One asks oneself if, since Sergio and Sergei is a story of human affections despite the difficulties (of resistance and solidarity, in short), so much prominence should have been given to the sickly paranoid subject Guerra incarnates (who at moments steals the story’s center of interest), which at moments makes Sergio and Sergei descend to the formula of the film of mix-ups and even surrealist.

The only answer that comes to me is that the character of Guerra functions well as a comic relief that compensates for the apparent seriousness of the rest of the story. However, that concession does not justify that the key sequence of the film be boycotted by one of the most hilarious moments of recent Cuban cinema: there where, while Sergio from Havana is able to guide Sergei on the spatial walk from which his survival depends, the security guy gets the proof he was looking for and comes out detached in his own weightlessness, in a situation that breaks the realistic pact of Sergio and Sergei.

That sequence is in itself contradictory: the summit of a film of affections ends up being a comic climax, to not say entertaining.

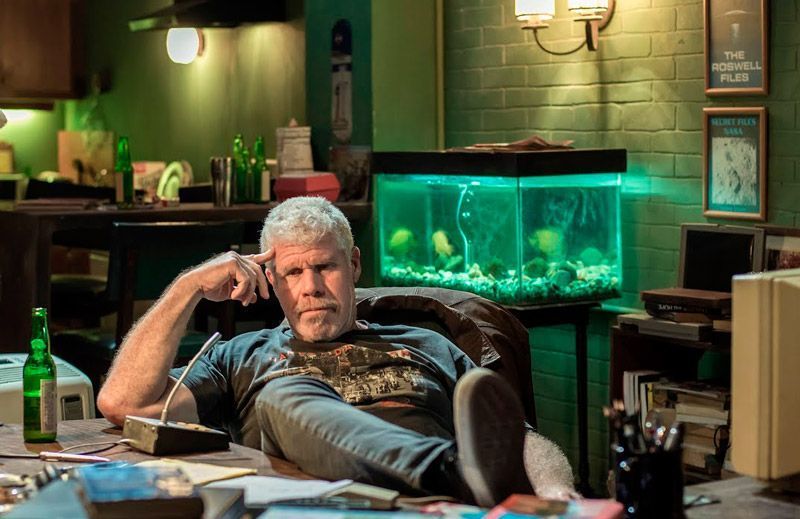

This second contradiction is displayed better under the second weighty subplot of the film. Sergio’s friendship with the also radio ham Peter from the United States, played by Ron Perlman. This character operates as contributor and facilitator for the protagonist. But its subplot has a special content: Peter operates in a conspiratorial world of spies and secret agents, the mis-en-scene of his scenic universe (a nocturne room, a closed sphere with a window through which we see a fragment of Manhattan) seems taken from a second-class noir movie. Certain incidents that involve him (that fixation with CIA and NASA secrets; the persecution he is submitted to) seem part of another story, and even the tone of his narrative loop is alien to the general tone of the film.

Such tonal confusion and generic mixture (social historic drama with vernacular nuances, nonsense comedy, noir with espionage overtones) give rise to a maladjusted film, at times incoherent and full of underlinings that subtract fluidness from its enjoyment. It is what the sensation causes, despite that it is a Daranas film with an exceptional narrative exercise in Cuban audiovisual fiction writing, that with Sergio and Sergei we are before a badly told story. Although we would have to pay attention to the reading of critic Antonio Enrique González Rojas, who analyses the triple protagonist aspect of Sergio-Sergei-Peter as an attempt to symbolize the meeting between Cuba, the USSR and USA, drawing characters-theses, more than psychological, and taking into account the interest for the national allegory in Cuban cinema.

I also have a hypothesis for the badly resolved hybridity: Sergio and Sergei was designed as a global product, as a film that would appeal to the most heterogeneous spectator. In its way, it prefigures the Netflix “Cuban cinema” category: local stories with global appeal. It also proposes to speak to a generation that came after the paradigmatic collapse of 1990-1991 and knows very little about such a circumstance. And an international actor like Ron Perlman is included in the cast.

No other purpose explains the existence of that invisible narrator, of that voice (Mariana, Sergio’s daughter, who tells the story from the future) that above all anchors and explains questions that are clear for Cubans by just seeing them. Try if you like a version Sergio and Sergei without that recourse. It will not be missed. Therefore, it is not needed (say the script handbooks). I repeat: for the Cuban spectator, because outside our context, a common individual requires that he be explained the why of the plot of a society like the Cuban in such historical circumstances.

Sergio and Sergei illustrates the emergence of a global format that could make it possible to stop speaking of Cuban cinema to refer to local productions that have access to global marketing made scenarios. Before this one, Mediapro and RTV Comercial collaborated in Esteban (Jonal Cosculluela, 2016). Both titles share an inclination toward the melodrama in the current Cuban audiovisual, which in the two cases also tend toward the feel-good movie.

Since everything has to be said, such production opportunities make it possible for Daranas’ film to have a quality postproduction above the average in Cuban cinema. Both the realistic recreation of the phenomenon of the weightlessness as well as the outer space environments and the touch ups of virtual scenography would have been very difficult to achieve with the experts and resources that exist for this in Cuba (Cubans Jorge Céspedes and Víctor López were key in the design of the digital mock-ups, on the other hand).

Daranas is clear about this, I believe, when he confesses not being sure that Sergio and Sergei is a film for festivals. If by this we understand a cinema of formal search, of author, of self-expression, whose commercial exploitation circuits should therefore be reduced, of course it is not. Joel Ortega, general manager of RTV Comercial, also knows it: RTV Comercial has bet on the result. We are constantly seeking projects and filmmakers to bet on their results.

I repeat that we spectators don’t usually pay attention to those initial screens of a film. I insist that through them many of the keys of the subsequent discourse are explained.