A bearded man in fatigues, as if he had just come down from the Sierra Maestra, serenades a young woman, while a poster of revolutionary Cuba reads: “Youth, joy and cold Coca-Cola.”

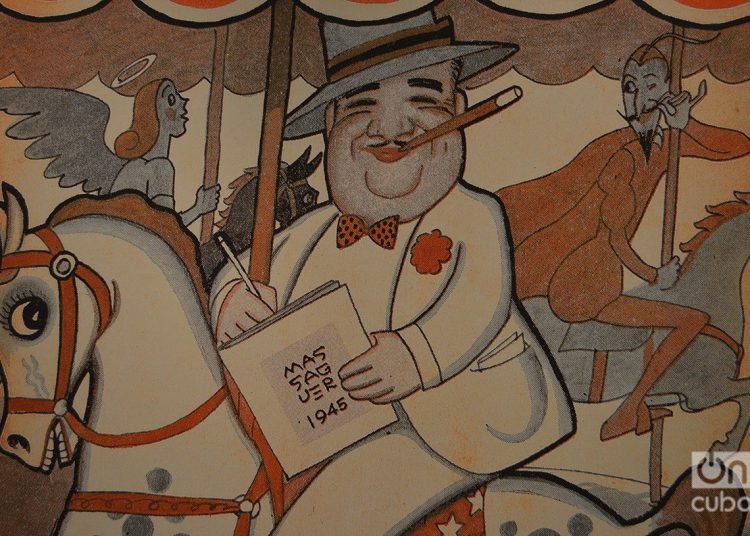

The unusual drawing was published in Cuba by caricaturist, illustrator and publicist Conrado W. Massaguer (1889-1965), just after the triumph of the Revolution, when advertising and business coexisted with political propaganda and nationalizations.

As in the river mouths when they reach the sea, where the water is neither fresh nor salty, or both at the same time, Massaguer managed to publish a whole volume dedicated to the new times of post-1959 Cuba, before its main private publications were closed.

“Advertising is to help Cuba,” reads one of the drawings, with a bearded character reading a newspaper that advertises brands such as Cigarros Hatuey or the U.S. Jell-O.

These and other works by the prolific Cuban illustrator make up the exhibition Cultura y caricatura cubanas: El arte de Massaguer at the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami Beach, Florida.

The idea of starting one of the most complete exhibitions of Massaguer’s work (and the first of its kind in Miami) arose from the work of U.S. collector Vicki Gold Levi, editor and curator of photographs and historian.

Before collecting Massaguer’s originals, magazines, objects, letters, Gold Levi discovered him through Social magazine, during an investigation for the book Cuba Style, co-written with Steve Heller.

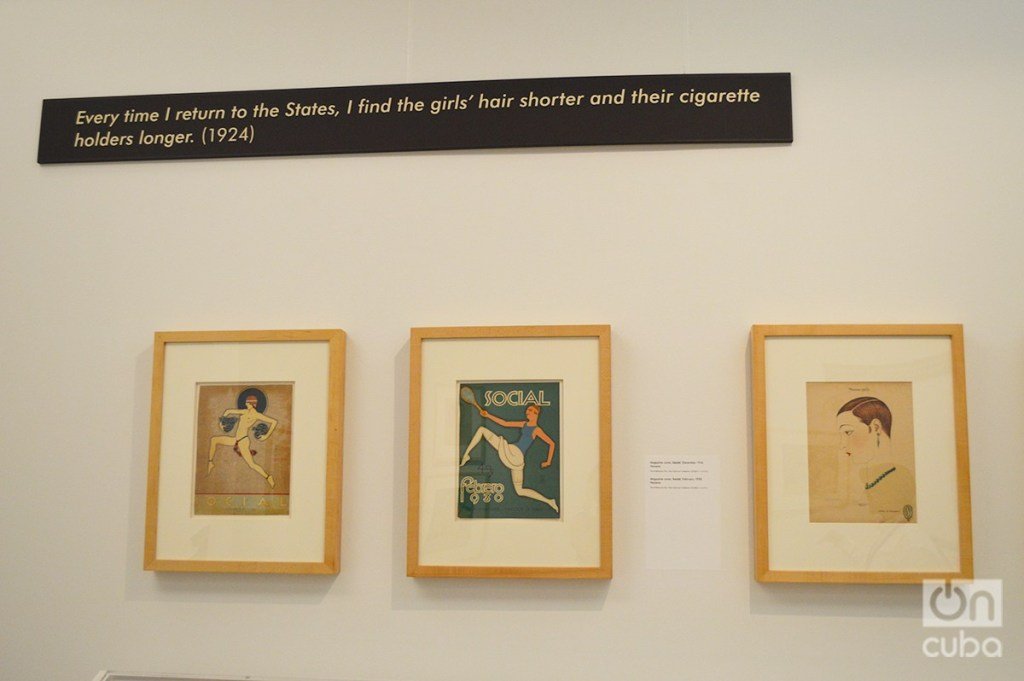

Social was a “lifestyle” magazine founded by Massaguer that for more than three decades highlighted not only his work but also that of the best illustrators and draftsmen of the time in Cuba.

His famous “Massa-girls,” an artistic representation, idealized and it could be said vindicative of the women of the time, with short, modern hair, drawn in an art deco style, appeared in its pages and covers on numerous occasions, said Frank Luca, curator of the exhibition and head of the librarians of the Wolfsonian Museum.

“Even in the caricatures of American tourists to promote the Island, the illustrator chose to ridicule only the male escort, in a burlesque tone that he did not use with women,” said Luca.

Other magazines where he published were El Fígaro and Carteles, also donated by Gold Levi to the institution for the collection.

During her trips to Cuba in the early 2000s, Gold Levi monopolized everything she found of Massaguer, and she continued to study in depth his work and his life. Next November she will make her seventh trip to the island, although to buy something new it will have to be “very special or unique,” said the collector.

“I was dazzled by his ingenious graphics, by his lines, so pure and simple yet expressing so much,” she said.

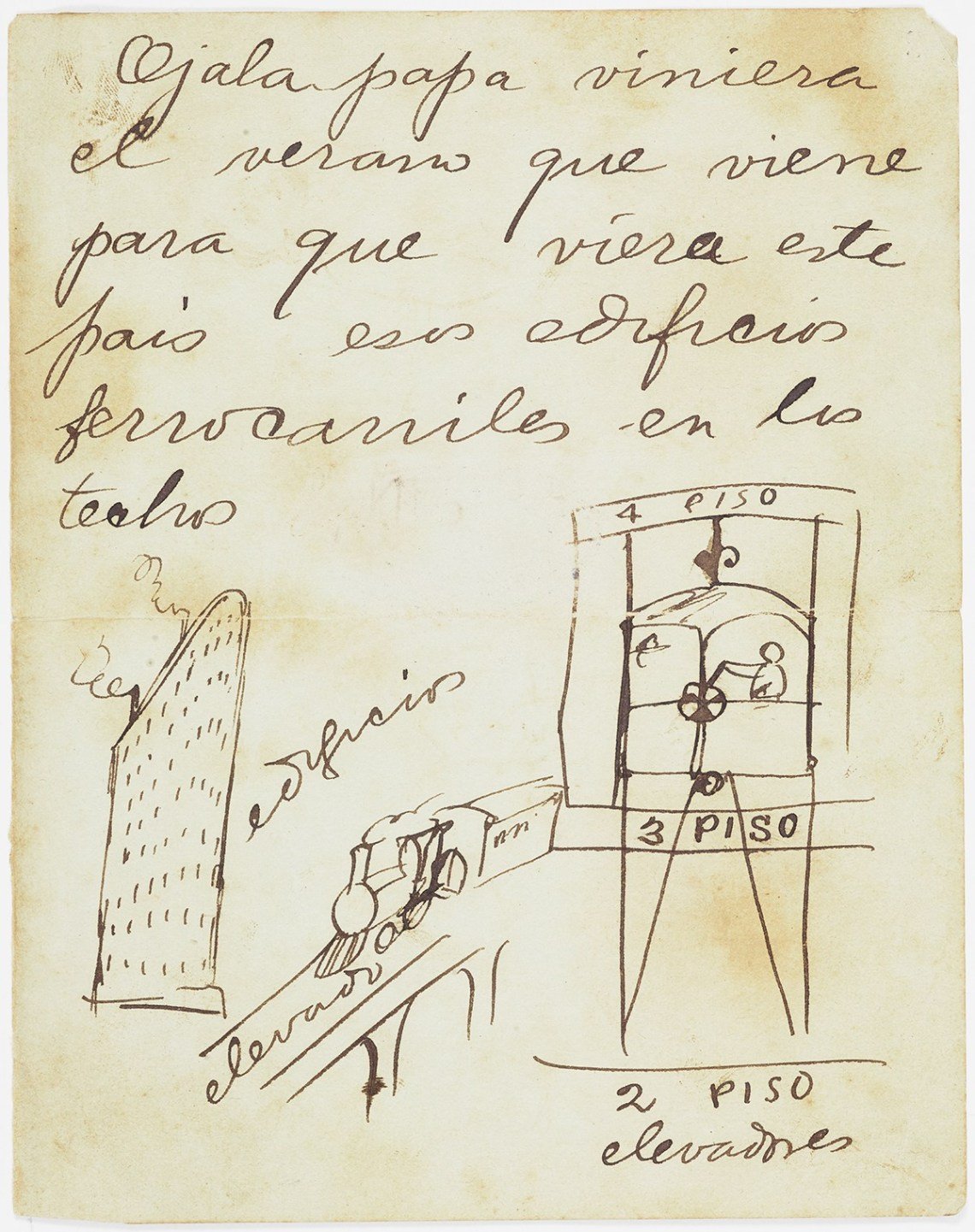

However, the exhibition has two favorite objects that do not reflect a mature stage of the artist, but his most intimate side. The first is a letter addressed to his father and his uncle, with the first known strokes of the artist where he showed tall buildings and the Manhattan tram, when he was studying in the cold Upstate New York.

The second is a rocking chair he made for the firstborn of a good friend who lived in Miami, decorated with his strokes and preserved almost intact to this day.

The value of the work of Massaguer, internationally recognized for his work in U.S. magazines such as Vanity Fair, Life, Cosmopolitan and Collier’s, reached the point of unleashing a wave of fake pieces that are sold as authentic.

At the beginning of her collection, Gold Levi acquired one of those false drawings, also on display in the exhibition, in this case about Albert Einstein, included in the “Ellos” section of the Social magazine.

His caricatures are not lacking in the exhibition. Although they were not faithful portraits (nor were they trying to be), explains Luca, his economy of strokes, humor and imagination, captured the essence of the character, easily recognizable in every instance.

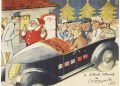

Thus the main world leaders during World War II are shown playing dominoes, or going to a gas station at Christmas.

In addition, his pencil drew numerous figures from Cuba and the U.S., from the Cuban Capablanca to the American Walt Disney, at a time when Havana was a meeting point for artists and famous people from all over the world, especially from the United States.

The director of the Wolfsonian Museum, Tim Rodgers, said at the opening of the show that “this new material marks an exciting volume that proves how our cultural exchange was really a two-lane road, paved in part by Cuban artists and trendsetting creators.”

“Sharing Massaguer’s history right here in Miami, a gateway to Latin America, is very appropriate,” Rodgers said in a statement to the press.

The exhibition, open until February 2020, is a trip to the Cuba of the past and relations between the two countries through the traces of one of the best Cuban caricaturists and illustrators of all time, who in one of his self-portraits used a demon and an angel as companions. Good and evil in his caricatures, picaresque and ingenuity.