In Chechnya there is no homophobia. Rule out a miracle. The thing is that there are no homosexuals, the authorities allege, making them invisible with one rhetoric swipe in that Russian republic of the Muslim Caucasus.

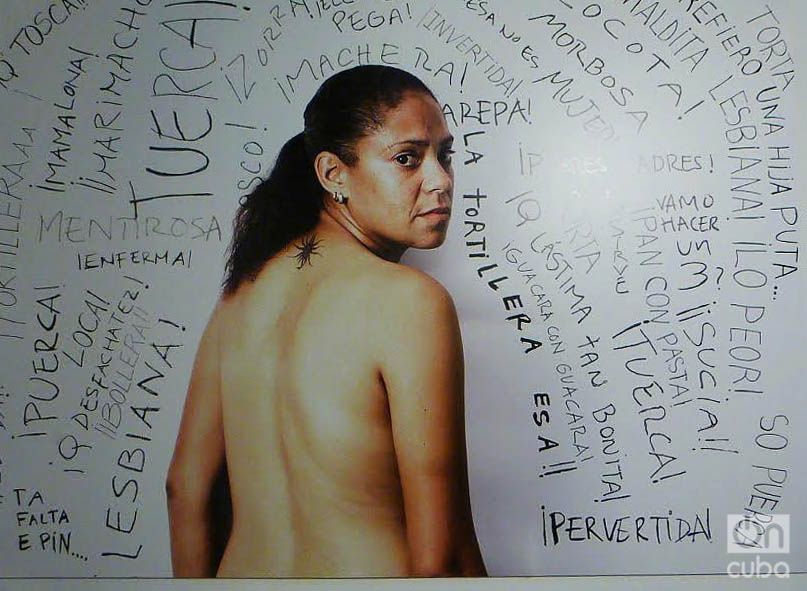

In Cuba there is homophobia, because of different reason, and certain art areas are helping to combat the phenomenon, delegitimizing it and placing it at the level of the social view, making it visible.

“The spaces and manifestations where a different sexuality can be expressed are scarce and have their very defined borders,” complains Yanahara Mauri Villarreal (La Salud, 1984), in the middle of a vertigo of mass photos from her homoerotic phantasies and taken with “a semi-pro Nikon D3100 and some Russian flashes” in an exercise of scenic minimalism set up at home. “There are photos I have shot in the street, using a wall as a background.”

“With these images I try to erase those borders, to free the individual of the weight of a tradition plagued by heterosexist formulas of seeing pleasure, the erotic and interpersonal relations,” says Mauri, a queer art activist, in an exclusive for OnCuba.

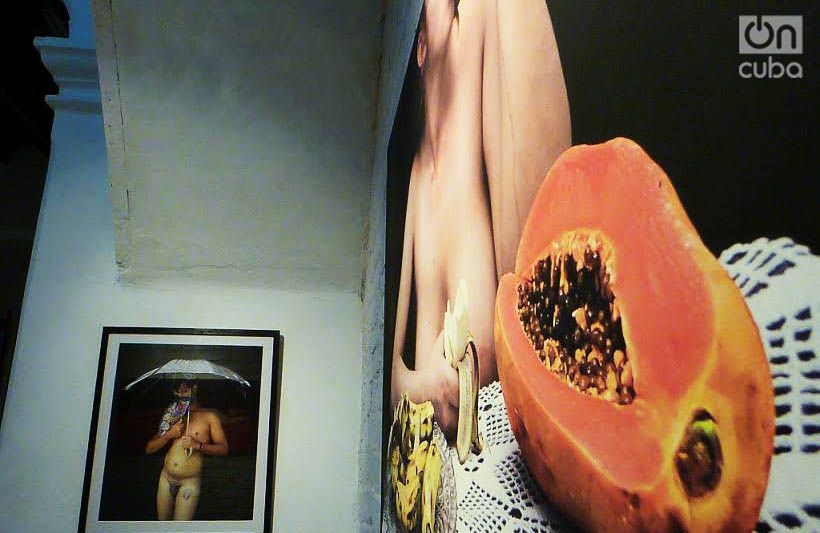

It’s Los hijos Onán, a fleeting 10-day personal exhibit in the discreet studio of painter Nasco. The space, built into one of the old artisanal roof houses of (214) Espada Street, is just a few blocks away from Havana’s first colonial cemetery.

One of its thick walls still provides evidence of the existence of funeral niches, a spectral solemnity that contrasts with the extroverted and bustling life of the street, in a barrio imbued with traditions: from the domino game in the middle of the sidewalks to the Santeria “works” on a corner, passing through the chatting and the bantering among neighbors. Behind such routines, mentalities that support them crossed by stereotypes, distrust and censorship.

Mauri Villarreal probably placed her display in a hostile? adverse? or perhaps indifferent? Territory. In any case, it serves as an experiment. Here the machos with tattooed deltoids and the girls with arabesque fingernails and formidable silicon breasts, would hardly place a foot in the display, despite the fact that in Los hijos de Onán “I not only deal with the homoerotic subject. Although I do prioritize it, I deal with other areas related to sexuality and eroticism.”

The photographer, a History of Art graduate from the University of Havana, is against anything that is watertight and her aim is to universalize her proposal: “I’m interested in that it reaches as many persons as possible. This series not just remains in the ‘queer community,’ nor should it do so.”

BORDERS OF SMOKE

Are we before a provocateur? “In my work I am interested in provoking, in expressing certain problems that are present in daily life,” she says without blushing.

And there can’t be any doubts. Yanahara’s photos printed in different supports – canvas graphics, photographic paper and vinyl on PVC – do not leave spectators indifferent. They narrate risqué scenes, with a high sexual voltage with explicit genitals, poses of seduction and of offering, sensitive textures through fruits and musical instruments, or cutlery utensils for repressive or sadistic purposes over the body and psyche. Other works are short filmed performances, where the biological identity of the individual is annulled or is subverted in the face of the action’s affectations. Borders? The artist seems to say: No, thank you.

“I’m speaking of freedom, of acceptance, of respect, of difference, but I am also discovering the mechanisms of power and oppression that operate in our society and in the world.”

Some spectators could consider these scenes pornographic. Were you aware you were running that risk?

This is not a series to please. It is true that some images are stronger than others, and I precisely don’t censor myself when it comes to creating. I’m interested in using diverse languages that perhaps at times can be associated to porn. I believe that freedom of expression is an idea that can use dissimilar visual codes, as long as you know how to say what you think with images, and that that concept be of value for the spectator.

Can Los hijos de Onán be considered activist art in favor of the queer community, among which you assume yourself?

Yes, this essay is important in the “queer community,” in quotes, because I don’t know if there exists in Cuba a community but rather persons who live their sexuality in an isolated way. In any case, it enriches the vision of an art of this type on the island, not just from the photographic point of view, but also from a socio-political aspect.

GIVE-AND-TAKE

Yanahara wants lack of inhibition in her composition maneuvers. Therefore she invites her models – the majority friends and acquaintances – to collectively build the photo, so that the area of decency can bilaterally be traveled naturally. “It’s not just shooting a photo. With an unknown or even with close persons it is a process, we talk during the session so everything flows. The person behind the camera is also a person who needs security before the person who is posing.”

The artist, who had the backing of the Norwegian embassy for her project, manages the photography concept based on diverse sources. Her own ideas and attentive ear to others’ experiences, that of her models or of “the same persons you meet in the street: a gesture, a phrase, a face can already be the photo.” The following step is the sketch and finally the production before pressing the shutter.

In Los hijos de Onán – a biblical character that incarnates the sin of the interruption of the coitus, although others take it as a referent of masturbation – the majority of the photos transpire an air of freedom in which the individuals float a self-affirmed identity in the face of pleasure.

For the author, that dignity or distinction, even from a certain angle of self-confidence, can be taken as a symbolic victory of those discriminated against in the face of centuries of oppression, death, abuses, stigmatizations and disdain.

In a certain way, the presentation photos of Los hijos de Onán is a wink to such a state of things. The artist appears in it together with her couple, linked by the shoulders and the waist, with a sky full of stars in the background. They are wearing motorcycle helmets on their heads, alluding to spacesuits. A cosmic love, yes, but also heads protected against possible crashes with reality.

“The ‘Other,’ the different, always tries to be hidden, rejected, minimized, etcetera. We see it constantly in the films, the soap operas, music, the mass media, not just in Cuba but also in the world,” says Mauri Villarreal, who in 2010 won the Cuban Phototheque prize in a small-format – 5×7 – contest for her collection “Los espasmos de Venus.”

NEEDS AND CHALLENGES

When the world day against homophobia – May 17 – approaches, Yanahara perceives that a heteronormative society like the Cuban one has entered a dynamics of change that favors the emergence of the queer community, already distant from “past times characterized by a highly homophobic climate.”

However, the changes are slow in coming and at times show signs of zigzags. There is a deeply conservative and irritated acting Cuba, beyond an apparent tolerance towards gays that is more the daughter of the social acquiescence than an ethical deliberation.

Despite the institutional efforts of an entity like CENESEX – National Center for Sex Education – “work must continue from all possible spaces because manifestations of physical as well as psychological violence are still being experienced,” the artist claims and asks the media and the school for more participation in the culture of debate.

“We need a society that respects and accepts the difference, not one that creates molds that exclude. A world day against homophobia does not resolve a centuries-old problem reproduced in the minds. In fact, the day goes by and afterwards everything continues being reproduced as before…and the other days of the years?”

Even with less spirit and predominance than before, the heteronormative exercises continue and will continue in force, especially empowered in their great reservoirs: the oldest and most reluctant generations.

If a more than 60-year-old lady stands at the door of the studio and asks what is being exhibited there, what would you answer?

Art and life is being exhibited here.