Photo: Néstor Martí (OHC)

Anyone that listens to him talk would think that Eusebio Leal grew up surrounded by libraries and embroidered tablecloths. However, it was another path that led him to become one of Cuba’s great intellectual figures and the main person responsible for the rehabilitation of Havana’s historic quarter, Habana Vieja, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

He began working at the age of 16, and that was also when he achieved a sixth-grade education with great sacrifice. Since then, his self-taught education has resulted in his significant work as a historian, various honorary doctorates, and an extraordinary number of awards from around the world for his restoration work.

This interview is about Leal’s dreams. Those dreams, which he says are intertwined with his aspirations and his agonies, help him by preventing something that was once described by Simón Rodríguez, [Simón] Bolívar’s teacher: “I wanted to create a paradise for all and created an inferno for me.” However, he continues to have one preoccupation: continuing his life’s work, with Havana as his horizon.

What sets Havana apart from other cities in the world?

Like people, each city has its imprint. More than a set of definitions or memories, Havana is a state of mind. People come and they wonder, ‘What is it that makes me feel so good, that makes it so pleasant to be here?’

Havana is eclectic, like Cubans; a synthesis of classic, modern and contemporary architectural elements, of art nouveau, going all the way to the Cubanacán art schools. We don’t know what would happen if that urban outline were to be dislocated, that very special design, where you can travel the length of the Malecón from the city’s newest spaces to its historic quarter, always looking out to sea. Havana is an insular city, a port city, a city where ten, fifteen, twenty thousand people sit along the Malecón at night to talk, look and enjoy the breeze. Havana is a city that looks to the world.

The argument has been made than an absence of real estate investment has made it possible to preserve the city, but it also has contributed to its progressive deterioration. What is the extent of that deterioration? What would be indispensable to save?

About what is happening or may happen, we have an opinion; about what has happened, we can only pass judgment. Certainly, we tend more to build than to preserve. Now, preserving the city cannot be an exercise in wealth; rather, it should be an investment based on our poverty, because without conservation, we would be left with nothing.

The city escaped the speculation and construction boom of other Latin American cities — where the first to suffer is the historic quarter — that occurred in the name of “modernity.” In Havana, that “modernity” is represented — very badly — by the so-called “coffin building” on the Malecón. That is what was awaiting us. Another symbol is the former building of the San Gerónimo University College, which was destroyed in the 1950s to build a heliport, located wall-to-wall with the Palacio de las Capitanes Generales [headquarters of the Spanish colonial rulers]. What insanity! What a loss! What a loss of memory!

Havana is one of the largest urban concentrations in this part of the world. It is a city that was determined at different moments, from its original plans to the Plaza de la Revolución. The new city center spread out to those large buildings, which, when preserved in an appropriate environment, are grandiose.

A city goes through processes of death and regeneration that are natural to a certain point. The city is so susceptible that when you work on it, something wonderful is reborn. That is what happened with the so-called House of the Green Tiles, at the entrance to Quinta Avenida, and it is what we are doing now with the Capitolio. That is how a return is made from that time of wear and tear, and the city’s preservation begins to be seen as a necessity.

I like to climb up to the roof of the Hotel Saratoga to appreciate from there the urbanism that sets us apart, and to contemplate the large gardens around the Capitolio, the Prado, and the Parque de la Fraternidad Americana. Now we can see the city with its virtues and not just its defects. Havana is in motion. Today, the Teatro Martí is being restored; the Gran Teatro; the Capitolio; the Malecón, the University; Colón cemetery; the Prado. The time will come when all of the pieces of that puzzle will finally come together.

You have said that cities are not just designed; rather, they are made by the people who live in them. How is that conception of the city as a living thing connected to the needs of restoring an inhabited historic quarter?

To a certain extent, a project is always a straitjacket. We have been learning through trial and error. I always said that “those who would die if they left should stay, and those who would die if they stayed should go.” Many came to Havana out of necessity and situated themselves in houses that always had room for one more. As a result, habitability has been threatened by problems of overpopulation.

To take one of the buildings of the Plaza Vieja as an example, the one with the stained-glass windows, we remember that more than sixty households lived there, most of them with four to six people each. To break with that precarious situation, restore the building and ensure better living conditions, it was necessary to create 104 new apartments.

When we are going to restore to reinhabit — because fourteen families returned to that building — those who leave are guaranteed a decent home. That involves different problems, and sometimes unusual things happen. You might have someone who wants a “breakdown” — one of those magic words that only we Cubans are familiar with —, a dreadful thing that can consist of wanting three apartments for the one that person had at the time, because he is divorced, but lives there with his daughter and her husband, who are also divorced, and the daughter has nowhere to go, etcetera.

That is why the process has been one of profound dialogue with the community, and sometimes arguments. We have done the reorganization from above, but we have also tried to do it from below, by maintaining a dialogue that is manifest in the hundreds of letters that I receive, the ones that people give me out in the street and in the deliberations of the Plan Maestro (“Master Plan”), the multidisciplinary entity that is drawing up a comprehensive vision of what is happening in the historic quarter by including the at-risk population, work with senior citizens and people with disabilities and a gender-based approach.

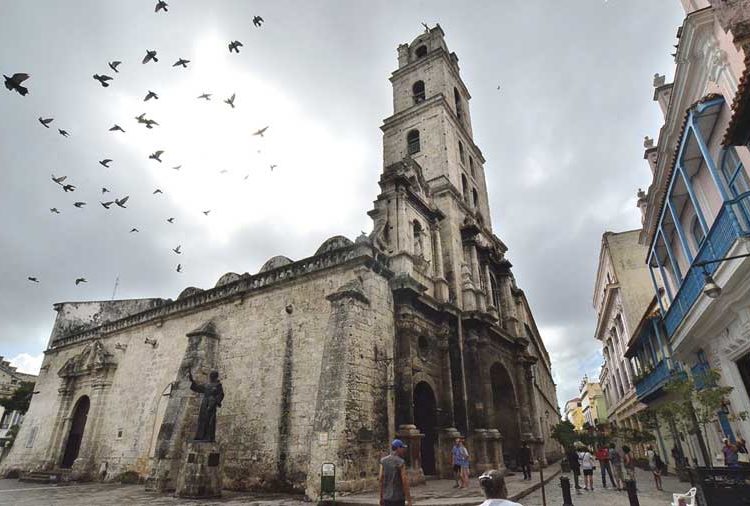

The historic quarter has been a laboratory. If we could bring together the elements that have been restored but are geographically dispersed throughout the city, our restored heritage would be three times larger than that of San Juan, in Puerto Rico; four times larger than that of Cartagena de Indias, and more monumental than both of them. The monumental character of Havana is also a sign of its difference: it is not a quaint little town; it is a big city, where the great Plaza de San Francisco and the great Basílica Menor del Convento de San Francisco de Asís coexist right next to a small fisherman’s house.

There are many tributes that the City Historian’s Office has lavished on individuals connected with the history of Havana and our country. What is the best monument that can be conceived for the work that has been done here?

The Basílica de San Francisco de Asís. When I was a child, the basilica housed a government ministry, but as an adult, I knew it as a market. Tons of vegetables would be piled up there, and in the middle there was a refrigerated area for storing meat. Later it was used as a set for a TV soap opera. Finally, it was left to the fleas and oblivion. The symbol is, then, the basilica when Fidel Castro enters, with it restored, and takes off his hat in front of the crucifix that hangs from the stage. That is the moment that I want to remember, the moment when we were able to turn around forgetfulness, destruction and vulgarity, and pure reason triumphed, even if that is somewhat romantic. That romantic vision of the world is the only one that can revolutionize something that is apparently lost.