[See here first part of this article ]

What happened in the U.S. presidential electoral campaign between Sunday, March 15 and Tuesday, March 17 of this year, confirmed some observations that were made in the first installment of this work. First, the Cuba issue came up again in Sunday’s debate between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. And it appeared in terms that brought back the times of the Cold War.

The question that the Colombian-American host, Ilia Calderón, of the Univisión channel asked both contenders was typical of what could be heard in the United States in McCarthyite times . It had nothing to do with the campaign or their position on a foreign policy issue. It was a typical question of what in the United States is called “red baiting” (which could be translated as “anti-communist sensationalism”). A rational response from the candidates was not pursued, but a stirring emotional appeal to certain types of voters: preferably extreme right-wing Cuban-Americans.

Senator Sanders responded as he had done a few weeks ago, with an analysis of reality from the perspective of an American liberal who is opposed to the existing socialist systems in the world, but also to right-wing dictatorial regimes (calling both types of government authoritarian), and that he believes the United States must be consistent and respect international law, maintaining relations and taking advantage of the good examples that exist in all countries, regardless of ideology. In other words, he refused to make an “anti-communist agitation” statement.

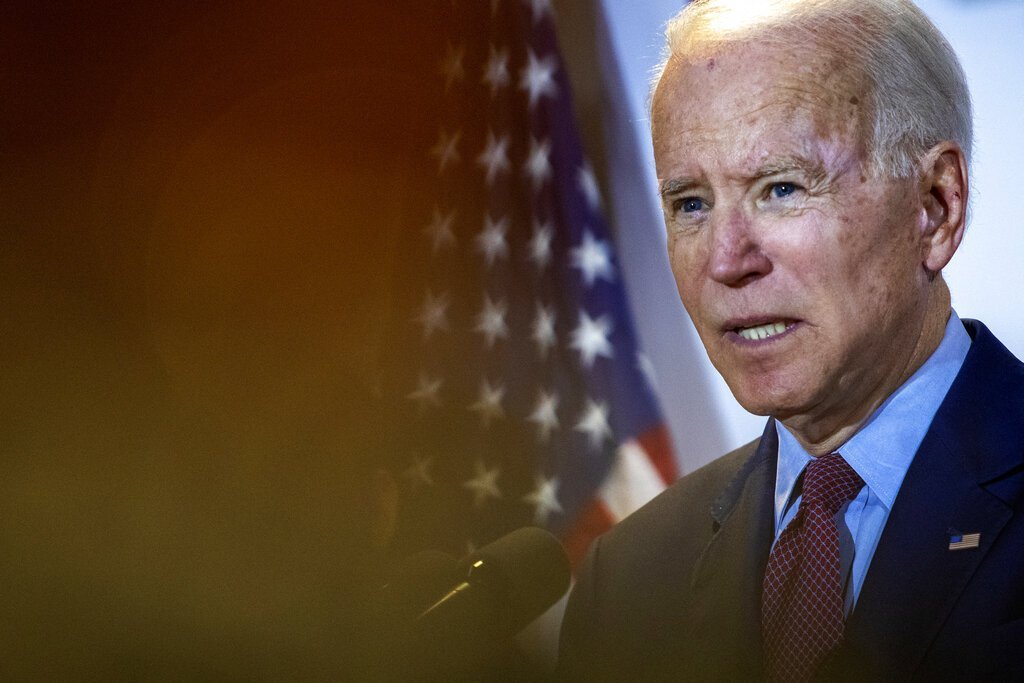

Vice President Biden, by contrast, responded with the kind of stereotypical phrases typical of the Cold War that were, of course, designed to win as many votes as possible in the upcoming primaries that took place on Tuesday. It mattered little that his own wife, Jill Biden, had visited Cuba in 2016, and pondered certain aspects of the Cuban reality that she saw with her own eyes, in very similar terms to what Senator Sanders did, arguing that this was the reason why President Barack Obama’s policy of normalizing relations and advancing cooperation was a good idea.

The primaries on Tuesday the 17th practically ensured that Joe Biden will very likely be the Democratic Party candidate who will face President Donald Trump. Actually, the Cuban-American vote was not relevant in this victory for many reasons that would make this text very long.

Today’s question that would inevitably have to be asked is how does Biden intend to approach the Cuba issue in the next stage of the presidential electoral process, when he faces Donald Trump?

Will he be able to repeat his performance on Sunday night in front of an opponent who beats him in using any kind of argument, no matter how scathing, to justify his aggressive policy against the Cuban “dictatorship”? Will he again make concessions to win the vote that will ensure his victory in Florida?

If he does so, won’t he be forfeiting the possibilities of returning to the normalization process, as he affirmed he would in responses to a questionnaire that the specialized magazine Americas Quarterly asked him?

In this second installment of this work, which covers the years and campaigns between 1980 and 2000, some keys aspects that can help unravel these issues are discussed.

[See here first part of this article ]

When looking at the relationship between the Cuban nation, its emigration in the United States, and the presidential electoral campaigns in that country after the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, it can be seen that they have gone through different stages. The first installment of this work focused on the initial period that elapsed between the 1960 and 1980 elections.

In that period, Cuban emigration behaved as an instrument of a course of action already established in Washington that did not consider it necessary to take it into account for anything other than as executors of the policy already elaborated and established, which aimed at “regime change” by coercive means and through various tracks: economic, diplomatic, political, and paramilitary or terrorist.

In the design followed by the different administrations of the time, the original emigration was expected to supply the human resources for the last two tracks. However, the third track was quickly rendered inoperative as it was unable to achieve its objective, the establishment within Cuban territory of an opposition to the revolutionary government. However, many Cubans who left the country for the United States in those years were classed in machines dedicated to U.S. special services’ covert operations. This gave them access to the military and paramilitary apparatuses of the United States, participating in the Vietnam War or in covert actions in Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean.

It is important to keep in mind that, starting in the 1960s, a concept related to the typical Cold War national security strategy, that of containing the Cuban example, was incorporated into U.S. policy towards Cuba. This almost always took the name of “avoiding new Cubas,” which was applied, for example, in the Dominican Republic in 1965 and then in Bolivia in 1967, in the latter case resulting in the murder of Ernesto Che Guevara. It was fully deployed in the 1970s against the Nicaraguan and Grenada revolutions. Cuban-American operatives participated in many of these actions that took covert forms, which added extra value to this emigration that was even involved in illegal domestic actions such as the sadly well-known Watergate case.

This facilitated the transformation that took place in the relationship between these Cuban-Americans and the U.S. apparatus of power in the subsequent decades as of 1980, in which the slow but sure progress of the emigration’s insertion into the U.S. political system was fruitful. This second part, which covers the years and presidential electoral campaigns between 1980 and 2008, will examine this new interrelationship.

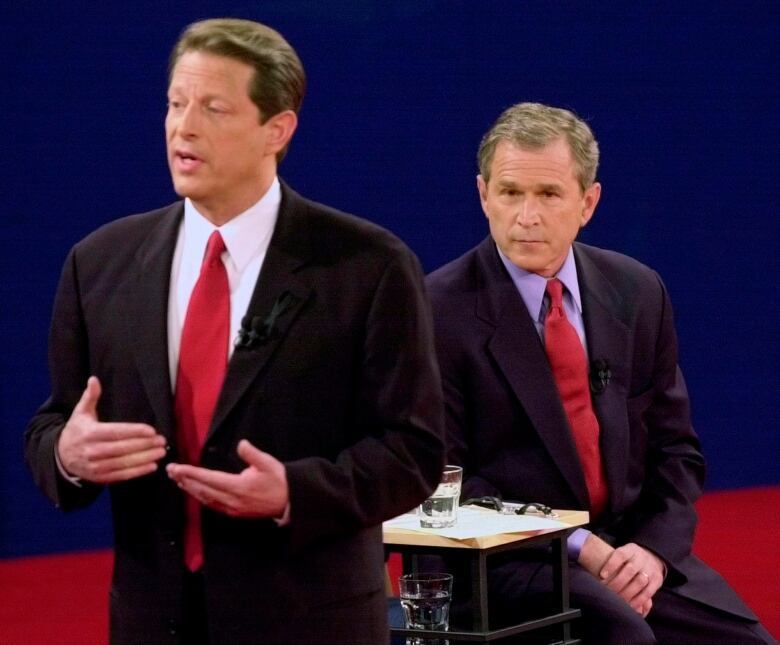

During this period, what happened with President Bill Clinton and his two electoral campaigns, in 1992 and 1996, and in the 2000 campaign, which precisely led to a recounting of votes in Florida that gave George W. Bush the victory in the Electoral College over Democrat Al Gore, after a long process of lawsuits that reached the Supreme Court, is very important. In all these campaigns, the role played by the so-called “Cuban lobby” made up of activists and politicians who had reached positions of power in Florida, but also in New Jersey, was significant.

1980-2008: emigration’s radical extreme right wing, the presidential campaigns and the Cuba policy

Between 1980 and 2008, the United States’ policy towards Cuba continued to be the same as it was originally designed in 1960 and modified in the second half of that decade, for example “regime change with prejudice” plus “containment of Cuba,” but was partly and negatively influenced by the emergence and activism in U.S. politics and particularly in the presidential campaigns of what we could call the hard core of Cuban emigration, which in political and ideological terms has a profile similar to that of a “radical extreme right,” although paradoxically, it is centrist towards economic issues. The period was opened by the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

As Jesús Arboleya recently pointed out,

“The creation of the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), during the government of Ronald Reagan, changed the ‘nature’ of the Cuban counterrevolution. From mere ‘instruments’ of U.S. policy towards Cuba, they became part of its elaboration and of the mechanisms in charge of influencing government decisions to implement it. The launch of Radio and TV Martí, as well as the approval of the Torricelli and Helms-Burton acts, during the governments of George W.H. Bush and Bill Clinton, respectively, were the most significant successes of this current.”

That original emigration resulting from the transformations brought about by the Cuban Revolution started calling itself “the historical exile” with the evident purpose of marking its differences with the most recent groups of emigrants who had left Cuba, especially those who arrived in the United States through the Mariel process, who were baptized with the sometimes pejorative title of “Marielitos.” It was also a strategy aimed at gaining political hegemony in the state of Florida.

Although a text like this cannot be extended very much in a matter that has been exhaustively studied by many specialists such as those already mentioned in the first part and by others such as Jorge Duany, current director of the Cuban Research Institute of Florida International University, it can be affirmed that with a mixture of elements of royal power and a well-designed public relations campaign, the image of an all-powerful monolithic national community, capable of decisively influencing politics in Florida and New Jersey, was fostered. This Cuban-American radical extreme right-wing also attempted to achieve hegemony in the academic world, creating the University of Miami Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies.

The fundamentalist narrative was often reiterated in the sense that, especially in Florida, due to its status as a pendulum state, no one could win elections without the support of this group of voters, most of whom were Republicans and demanded a “hard-line” policy and without concessions towards Cuba. In reality, these positions coincided and were validated by the United States’ own policy towards Cuba as it had been designed during the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations.

It cannot be denied that this first wave of Cuban immigrants, based on their own strengths (class origins, cultural level, network of contacts in the U.S. centers of power and support of the federal and state authorities, among others), managed to insert themselves in the American political system and gain a significant share of power in Florida, which was becoming a key state for the presidential elections. It also had some, albeit much lower, quota in New Jersey. Susan Eckstein, with her work The Immigrant Divide: How Cuban Americans Changed the U.S. and Their Homeland, has done an excellent study on this process.

Having said this, it should also be added that this “historical exile” was functional to the U.S. policy towards Cuba. But, above all, it was functional to the Republican Party in each of the presidential electoral campaigns that followed. It had a special place in that of 2000 and the sadly well-known vote count in Florida. Compared to other ethnic groups, only Jews and their pro-Israeli lobby have been more successful in inserting themselves into corridors of power, as Canberk Koçak has shown in his essay “Interest Groups and U.S. Foreign Policy towards Cuba: the Restoration of Capitalism in Cuba and the Changing Interest Group Politics.”

But the case of the Israeli lobby is very different due to the size of its presence in all areas of American society (including culture and the entertainment industry), its extension through several key states and its financial power infinitely superior to that of the Cuban-American. Additionally, it is a lobbying group that has worked with both parties, Republicans and Democrats.

One of the interesting paradoxes in relations between Cuba and the United States happened precisely when the so-called Cold War came to an end in a series of events that took place mainly in Europe between 1989 and 1991. On the one hand, certain circumstances caused that three conditions that the United States had insisted that Cuba had to fulfill before starting a process of normalization disappeared: abandonment of the alliance with the Soviet Union, withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola and a stop to support for the Central American revolutionary processes.

All this happened between 1989 and 1991, but for other reasons: the Soviet Union disappeared; Cuba withdrew its troops from Angola after a peace agreement through which the objectives that the Cuban leadership had set itself were achieved; and the Central American conflicts ended with a series of diplomatic agreements, to which Cuba contributed.

On the other hand, the influence of the “Cuban lobby” reached its pinnacle.

While the island was facing one of the most critical moments in its recent history due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the disappearance of the socialist camp that was its economic, political and military mainstay, the right-wing Cuban-American lobby, the CANF, reached the height of its political influence in Washington. It can be said that these circumstances created in their ranks a triumphant euphoria that gradually began to disappear due to the resilience of the Cuban government.

The long period of three presidential terms in which the White House had been in Republican hands, between 1980 and 1992, served this emigration to gain ground and influence supported by the White House and the Capitol. There is no doubt that in this period the image that “the Miami mafia” controlled U.S. policy towards Cuba was solidified. Paradoxically, the Cuban official propaganda during the “Battle of Ideas” and especially when the campaign was carried out to achieve the return of Elián González to his country fueled this legend that suited the interests of that “historical exile.”

This twelve-year period of Republican hegemony (1980-1992) was followed by an eight-year period (1992-2000) under a Democratic President, Bill Clinton, who won two electoral campaigns (1992 and 1996), and a similar one (2000-2008) presided over by another Republican, George W. Bush, who also won the Electoral College twice in presidential elections (2000 and 2004). However, the Republicans only won the popular vote in one (2004), which in addition occurred in exceptional circumstances, just three years after the attacks of September 11, 2001 and amid the euphoria of what then seemed like a victorious war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

In this 2020, the return of the Democrats to the White House after four years of what many consider a disastrous period for American foreign policy due to the ravings of President Donald Trump, could lead to the rectification in the policy towards Cuba and the return to the normalization process launched in December 2014, to the extent that the situation has some parallels with the 2008 electoral campaign.

For this it would be useful to take a look at the lessons derived from the campaigns of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, the last two successful presidents of that party, who have also been the two presidents under whose terms more progress was made in bilateral relations between the two countries. for the benefit not only of Cubans living in Cuba, but also of Cuban-Americans who came to the United States after the 1994-1995 migration agreements.

Although progress during the two Clinton terms was not as sharp or significant as with Obama, it is worth remembering that two important security agreements were reached in them: the one related to the fight against drug trafficking and the 1994-1995 migration agreements.

If the Clinton period did not produce more results, it was not because there were no conditions for it, but because of certain political errors made by his administration in managing relations with Cuba. Those mistakes should have been perfectly predictable if the President had followed his own instincts.

However, he made a mistake that he later regretted: he allowed the lobby of the “historical exile” to exert an excessive and unnecessary influence on his policy towards Cuba, by agreeing with it, which benefited him financially in his 1992 electoral campaign, but did not give him the hoped-for votes to beat George W.H. Bush in Florida.

In 2009, historian Taylor Branch published a book based on eight years of private conversations he had with his friend, President Clinton, at the White House between 1992 and 2000. In one of the passages from that work, titled The Clinton Tapes: Wrestling History with the President, Branch quotes the President as saying:

Anyone with half a neuron could see that the embargo (blockade) was counterproductive. It went against more sensible policies of compromise we had followed with other communist countries, even at the height of the Cold War.

He added that since 1980 “the Republicans had garnered the vote of the exiles growling at Castro, but no one bothered to think about the consequences.” By the way, in those conversations he also complained about the pressures by Bob Menéndez, also of Cuban-American origin, who in those years was Representative to the House for the state of New Jersey.

That appreciation by Clinton was endorsed by his own experience in contacts maintained during the 1992 presidential campaign. In April of that year, when he tried unsuccessfully to take the state of Florida from his opponent George W.H. Bush (the father) he went to Miami, met with Jorge Más Canosa, the then president of the Cuban-American National Foundation (CANF), and attended a dinner with a group of millionaires of Cuban origin. In exchange for their financial support and a dubious promise of official CANF equidistance during the elections, the future Democratic president publicly supported the bill that the Cuban-American lobby was promoting in Congress and which later became the Torricelli Act, which, incidentally, took its name from a New Jersey Democratic politician who became a Senator, Robert Torricelli. Torricelli was eventually replaced in the Senate by Cuban-American Bob Menéndez.

This process is very well described not only in the works of Kornbluh and Leogrande and Kami, but in the massive history (760 pages) of relations between the United States and the Cuban Revolution by the award-winning American historian Lars Schoultz, Professor at the University of North Carolina, titled That Infernal Little Cuban Republic: The United States and the Cuban Revolution.

Just as Clinton himself privately warned, given his support for the Torricelli Bill, which codified the blockade (embargo), President Bush (father) made a 180-degree turn from his initial position, which was to veto that act, and decided to support it despite the contrary opinion of the State Department, which argued that it violated a clear constitutional precept, the executive power of the president to conduct the foreign policy of the United States without the interference of Congress, and that it included an obviously extraterritorial purpose that would be rejected even by the allies of the United States. In fact, it was precisely that year that the Cuban government for the first time managed to get the UN General Assembly to condemn the blockade, declare it illegal and demand its lifting.

President Clinton was trapped in the tangle of the Cuban-American lobby, which tied his hands on a whole series of issues on which he intended to modify the policy towards Cuba. In exchange, he did not win Florida, although he did defeat Bush with his famous slogan “It’s the economy, stupid.” He watched as his new friends in Miami blocked his appointment of his first candidate for assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, Cuban-American black lawyer Mario Baeza.

Subsequently, he faced Más Canosa’s opposition to the signing of the 1994-1995 migration agreements with Cuba, which was in the interest of U.S. national security. The actions of Cuban-American extremists created the conditions for the tragic incident of the shooting down of the Brothers to the Rescue planes, which not only led him to sign the Helms-Burton Act, which he ultimately did not want to sign, but also sabotaged the secret negotiations being carried out with Fidel Castro through Gabriel García Márquez and Bill Richardson. The latter also happened in a presidential election year, 1996.

Finally, Clinton had to confront the Cuban-American lobby in the case of the boy Elián González, which dominated bilateral relations between the end of 1999 and June 2000, another year of presidential elections, elections that ended in the famous recount of the votes in Florida, which according to many observers was a fraud. It did no good for the Democratic candidate that year, Albert Gore, to have served as vice president under Bill Clinton, who is directly and indirectly responsible for the Torricelli and Helms-Burton acts. At the key hour, the Cuban-American lobby opted for the Republican candidate, George W. Bush. The Democratic candidate in the 2004 presidential election, Senator John Kerry, had no better luck.

According to studies that have been made regarding investigations on the ballot box, in those two elections (2000 and 2004) Bush obtained 75 and 78 percent, respectively. It can be said that in those years the Cuban-American vote for the Republican candidate reached its highest levels. Of course, because it is the U.S. political system, in which campaign financing is sometimes more important than real sympathies for one or the other candidate, voting is only one of the aspects to be analyzed.

However, and it is worth remembering this fact, George W. Bush’s policy towards Cuba prioritized the “historical exile’s” interests and vain illusions of “regime change,” creating the Commission for Aid to a Free Cuba and the office of Coordinator for the Cuban Transition within the State Department. The failure of that policy was evident in 2006, when the transfer of power between Fidel Castro and Raúl Castro in Cuba took place smoothly, as predicted by those sectors, whose action was extremely damaging to other groups of Cuban emigrants, leading to the prohibition on travel and limitations on remittances.

[See here first part of this article ]