The death throes of El trigal concentrating market were also the labor pains of the relaunch of the state enterprise Acopio collection center, a kind of phoenix that has been the recurring attempt of solution by the MINAGRI (Ministry of Agriculture), or of who directs agriculture in Cuba, of the marketing problems (contracting, processing and distribution) of agricultural products since my friend Goyo and I, a long time ago, used to “steal mangoes” in Morejon’s farm, famous at that time in my town. We did it less to eat and much more for the adventure. Collecting has been with us for good or for bad since that remote time.

I start from the supposition that all the Acopio workers are good people, aware of their work and imbued with its social value and I make it extensive to each and every worker in agriculture, including the Ministry. It isn’t a problem of women and men, even if it involves them. It is a problem of concepts.

Acopio has been the formula, the mechanism, the organization that MINAGRI and decision-makers have created to “guarantee,” among other things, control over production and producers, over distribution and consumers and because perhaps they can’t find a better alternative. Acopio has the monopoly over contracting, collecting and distributing agricultural products throughout the country.

It has to its credit countless articles in national and provincial newspapers, a good part of them highlighting its difficulty in “serving” its clients well, either because it leaves the farmers waiting and the products rot in the field, or because after picking up its products it leaves them in trucks for days (I remember that report from many years ago of bananas spoiled by the tons) or because it pays producers prices that have nothing to do with production costs in a time when a day laborer who works half a session can earn more than fifty pesos a day, plus lunch, plus a bag of extra products a week. Or because it simply delays payment to the farmers, who are not compensated either for that delay. Acopio today is an OSDE (Higher Organization of Business Management), a business group subordinate to the Council of Ministers and “attended” by the Ministry of Agriculture. But Acopio is just the tip of the iceberg.

A series of three articles under the title: “¿Producir todos los alimentos que necesitamos con la misma economía, con las mismas estructuras y haciendo lo mismo?” published on June 18, 22 and 26, by two colleagues, make us think about what’s under the surface. Of course, perhaps what most fueled our neurons was the Mesa Redonda TV program where three of the leading organizations in food production in Cuba appeared: MINAGRI, AZCUBA (sugar industry) and MINAL (food industry). Then came a hopeful report on the meeting of the country’s highest leaders with colleagues who work/direct the research centers associated with food production.

Searching under the iceberg

It’s true we’re in a hurry to fill the platforms, but it is convenient to understand the essential: the political economy of agriculture in Cuba, the relationship between those who participate in the structure that is the agricultural and industrial production of food in Cuba. The State (representing the owner, who is the people) usufructs through its companies the largest amount of land in Cuba, and it still has a large part of it uncultivated, cultivates with very low productivity levels another part, prioritizes its companies in the allocation of resources and produces a minority of the food. The private farmers who, with a minority part of the land, withstanding purchase prices of their products that often don’t offset the costs, produce the majority of the food. Is there a greater contradiction than this? Whoever manages and, in fact, owns the largest amount of land, is the one who least produces it and the one who obtains the least yields and also keeps a good amount of it uncultivated and delays the delivery of land to those who want and need to work it. Nor is there an adequate public policy that encourages those who have already received land and occupy some two million hectares, often without the resources they need.

*Caption:

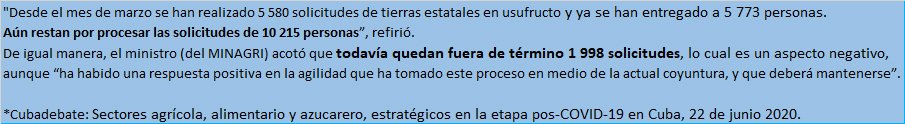

“Since March, 5,580 applications for state lands in usufruct have been made and they have already been given to 5,773 persons. The applications of 10,215 persons still have to be processed,” he said.

In addition, the Ministry (MINAGRI) said that 1,998 applications are still out of term, which is a negative aspect, although “there has been a positive response in the speeding up of this process in the midst of the current situation, and which should continue.”

Cubadebate: Agricultural, food and sugar sectors, strategic in the post-COVID-19 stage in Cuba, June 22, 2020.

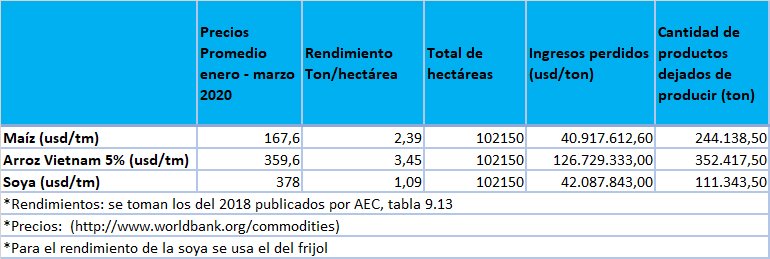

If we calculate ten hectares per person of the applications still pending to be processed they would be 102,150 hectares of land that now produce nothing. How much product stopped being produced in a year! Let’s use numbers to show it:

*Caption:

Average prices January-March 2020

Ton/hectare yield

Total of hectares

Lost income (USD/ton)

Amount of products not produced (ton)

Maize (USD/MT)

Rice Vietnam 5% (USD/MT)

Soy (USD/MT)

*Yields: those from 2018 published by the AEC, table 9.13

*Prices: (http://www.worldbank.org/ commodities)

*Soybean is used for soy’s yield

Having uncultivated land when there is not enough food! It is not a problem that emerged with COVID-19, it goes way back. Let’s multiply those quantities of products not produced in the last five years. In 1959, in just a few months, thousands and thousands of hectares of land were handed over to more than 100,000 farmers.

In 2018, Cuba imported 812,333 tons of maize, at a cost of 273,247,000 dollars; 496,120 tons of rice and paid 198,843,000 dollars and 329,529 tons of soybean cake, spending 152,385.000 dollars on it. You can also count how much could have been saved in any of these products, say maize, if the hectares applied for and not yet delivered had been cultivated. Then only 568,194 tons of maize would have been imported and 191,125,900 dollars could have been saved in just one year! Having idle land is not something to be laughed at.

The structures that have to do with food production in Cuba and that, in my opinion doesn’t only include MINAGRI,1 concentrate and centralize the commercialization of products in a state monopoly, they also centralize and monopolize the commercialization of inputs, administer the prices, often divorced from costs, delay the delivery of uncultivated land, have turned credit and service cooperatives into intermediaries, intermediates with low-efficiency and also monopolistic enterprises between producers and external markets, and fail to change radically that situation, maintaining structures that reproduce ways of doing that are archaic and divorced from reality.

These structures, in addition, have one of the most powerful systems of science and technology for agricultural purposes in Latin America, probably the best-qualified workforce in the region, capable of providing production systems, technologies and services in other countries of the world that unfortunately are not fully exploited in ours. It’s not for lack of science and researchers that we continue to get bogged down trying to produce food.

Let’s go step by step; let’s remove the bureaucracy from the farmers, let’s give them all the land they need, leverage them with soft loans, let them use their wisdom, gained day by day in the furrow. Let’s join them with the scientists, allow them to approach end consumers, Cubans and foreigners, let’s improve and update incentives. Let’s make the territories less dependent, let’s promote the creation of short supply chains and let’s promote alliances between the public and private sectors to reduce the transaction costs of these processes.

In our country there was a Revolution that began with agriculture, which took a stand with the Americans for having nationalized the land, which gave part of the land to the farmers, which taught them to read and write, and made it possible for their sons and daughters to be doctors and engineers, which allowed them access to hospitals and at that time modernized the Cuban countryside, even having more tractors per hectare than many countries in Europe, which has trained thousands of engineers in agricultural and livestock specialties. Let’s use the strengths, let’s not place more obstacles.

***

At the end of 1987―my son was a few months old―I was riding my Chinese bicycle, a sack-proof Flying Pigeon, and I would go to the almost nearby town of Alquízar (more than 25 km from my town) and its adjoining farms to find taro for the baby. Along the way I was accompanied by the idea that when his children (my grandchildren) were born, my son would no longer have to make that journey. Camila, his daughter, was born a week ago, and it seems that the taro is still hard to get, but also that it is difficult to find it, even in Alquízar, that I no longer have a bicycle and that a whopping 32 years has gone by. Oh, and it’s more expensive too.

***

1 Neither is it a problem of the men and women who work in this organization.