A law approving same-sex marriage, including adoption rights for same-sex couples and access to assisted reproduction, has been passed in a country that has a reputation for being exceptional. Achieving it was not easy. For more than a year, the churches and the most conservative sectors strongly opposed it and managed to resist a first attempt at legal formulation. The political solution was not to dictate it as a decree of the Council of State or approve it by the National Assembly, but to submit it to a referendum. Thus, it was approved by a majority, on September 26, 2021. Naturally, I am talking about Switzerland.

The Cuba of the early 1960s stood out for its great leap forward in terms of human rights. Before the integration of the political parties into one, the profound reform of the institutional system of the State, the declaration of socialism, a transformation of social relations and inherited cultural patterns were unleashed, starting with family life itself. This was expressed in the early independence of the boys and girls who left home to teach literacy in the mountains, to study in Havana, who formed part of the militias or went to cut cane in the savannahs of Camagüey, given over to unparalleled civic socialization.

In those years when new things happened every day, it also began to spread that those were spaces of perversion, where minors lived promiscuous and precocious sexuality. Those children were taken to Siberia, to brainwash, them with communism, and to turn them into robots at the service of the regime. In a typical contagion reaction, 15,000 children were sent alone to the United States, among them some of my cousins, under the “very reliable” tutelage of some churches, the same ones that advised against going to teach literacy, because it was equivalent to plunging into indoctrination and damnation. The history of Operation Peter Pan and its organizers, based on declassified files and testimonies of the protagonists, is available in books and documentary films for those who want to have an informed opinion.

Of course, most of those mobilizations and the social change that accompanied them were not encrypted in laws or codes. Civic socialization and the construction of a new political culture did not depend on regulations and rules but on social participation. In fact, once the great social reforms of the Revolution in 1959-61 were applied, that mixture of classes and skin colors, equalization of gender roles, mass access to education, health, employment, welfare, depended more on ascending social mobility generated by access policies, which made use of legislation as their instrument, rather than initiatives of the legal system.

The background swell of this decade of the 1960s, which is also idealized, left bitter experiences, reflections also of the political culture of the time, in particular ideological restriction and extremism, homophobia and discrimination of religious people. The purges of homosexuals, believers and those disaffected to the Revolution that occurred in those early years, prior to the Gray Quinquennium and the influence of the Soviet Union, derived from the pure and simple political conflict, as well as from prejudices implanted in the previous civic culture, but also of others that were part of the revolutionary harvest itself.

Anticlericalism, rooted as a political culture in the atheist leftism bequeathed to us by Spain, before Moscow, and present in the Cuban tradition of various colors, was exacerbated by the belligerent position of the churches, actively aligned against communism from very early years. The UMAP (1965-67), a mixture of military service and “schools of conduct” where religious people, homosexuals, disaffected people, and even young people sanctioned for various offenses were sent to “re-educate” themselves, was an emblematic fruit of that bitter harvest, although not the only one or the last.

If those who led the Communist Party in the 1960s, five decades later, learned those lessons, and rectified their atheistic and homophobic radicalism, it could be assumed that the churches would also have learned the lesson of their anti-communism, which divided the mass of believers. Disseminating anti-Family Code propaganda from the pulpit and disseminating it through the numerous printed and digital media available to those churches throughout the island, has not been a good example of preaching about love, coexistence and national reconciliation.

In any case, the government has had to thoroughly support family rights that concern gender equality, LGTBI, single-parent groups, the elderly, minors, affected by abuse and violence, and everything covered by this vast law of families. But it has also had to preserve relations with those churches, almost all of them conservative, as well as their right to free expression and discrepancy, along with that of citizens who defend similar values. In other words, they can’t be told “if you don’t like socialism, let them leave.” Politics has to be done, in the deep sense of the word, and it has to be done well.

Fulfilling the role of governing consists not only in issuing “legal” laws, but also in adopting legitimate policies, endorsed by citizen consensus. In addition to implementing consultation and promoting informed debate, it is necessary to ensure acceptable conditions for democratic functioning. The last reason for this functioning is constituted by the means of direct democracy (MDD), identified as the plebiscite, the referendum, the consultation.

The reason (or not) for the consultation and the referendum

I imagine that readers are not so interested in the details of the academic and doctrinal debate about the use of these MDDs, and in any case, this is not the space. I will only point out two aspects that seem to me to be of greatest interest, and which, of course, are relevant beyond our borders.

One: there is no unanimity regarding its use among jurists, political scientists, and other experts. Some affirm that if the representative bodies fulfill their role democratically, why consult and vote? Still others argue that these mechanisms facilitate “the tyranny of the majority.” They say that when they arise from a citizen initiative “from below,” they almost never go beyond “non-binding” consultations. And that when they arise “from above,” they lend themselves to government manipulation, sometimes by asking for the Yes or No.

Two: despite the above, the fact is that referendums, plebiscites and citizen consultations constitute a growing trend in many regions and countries, since the end of World War II, so that they have become common, both in “full democracies” as in “authoritarian regimes.” These experiences show opposite results to those mentioned in the previous paragraph. For example, the “non-binding” consultations have served to reveal fissures in consensus that gave rise to content changes in legislative proposals, as occurred with the draft of the Constitution and the Family Code itself in Cuba. Examples that the government does not win every time it calls and organizes a referendum were the No to the authoritarian regime of Pinochet (1988), and the other No, almost 34 years later, to the new Constitution of Chile proposed by a democratically elected government, both rejected at the polls by the majority of Chileans.

On the other hand, and as experience reveals, “the political ecosystem,” as it is said now, does not work like clockwork anywhere, nor in a fully democratic manner, in terms of expressing the interests and wishes of minorities as well. In any case, if it is about fidelity to the consensus, are the National Assembly and the State institutions in charge of legislating more legitimate than the direct and secret vote of all citizens?

Based on the premise of a happy world, that is to say, entirely just, rights should not be debated publicly, much less be put to a referendum. Perhaps they should not even be voted for as part of a new Constitution, even if the previous one had not recognized them. It would be enough for “the United Nations” or the “innate sense of justice” to dictate them to us as self-evident.

However, we also know that only about 33 countries in the world have recognized some of them as basic rights, let’s say, that of the LGTBI to create families and have children. Because rights, like people, are part of a historical era. So, instead of taking them for granted, we should understand that it is time to fight to extend them and make them accepted by all. Which does not happen by the grace of political will, nor of a legislation dictated by decree.

Was the referendum the most effective way to achieve it? Some described it as “an overly progressive and comprehensive law,” which risked losing the votes of “those who disagree with one or two aspects of the Code,” or outright the “punishing vote of those who blame the government for the economic situation they are suffering.” Wasn’t this the worst time to put such an ambitious and far-reaching law to a referendum?

This is a long and drawn-out issue, so I’m going to be short.

Paradoxically, for the first time the government has been criticized for “going overboard” in fulfilling a commitment, and applying a mechanism approved in 2019, along with the rest of the Constitution. I can imagine what would have happened if it hadn’t complied, claiming “it wasn’t the time.”

A second paradox was that of those who supported the contents of this bill, but instead of openly supporting its main promoter, they reproached it for “method issues,” and “having made concessions to the religious right,” changing the wording of the constitutional text in such a way that, supposedly, it blocked the possibility of legalizing same-sex marriage. Although the draft of the Family Code submitted for consultation proved that this questioning was baseless, those who prejudged it in this way never rectified their assessment of the article of the Constitution as approved in 2019.

Those who were suspicious of the bill, repeating that “Cuba is not Sweden,” that the Code was an imposition, and that the referendum was nothing but manipulation, never explained which part was “too daring,” rather than a mirror of social and couple relations really existing and accepted by the majority of Cubans in 2022. Nor which one exceeded the agendas of the movements opposed to the abuse of women and minors, the protection of the elderly and the disabled, in the world, including our region and Cuba itself.

On the other hand, the strategy of the drafters of the bill brought together in the same piece of legislation the interests and representation of the various groups and social subjects. In other words, if in other countries the cause of same-sex marriage has barely represented that of the LGTBI population as a whole, the diversity of groups and social sectors whose rights were directly involved in this comprehensive family bill created a connection between groups who were discriminated against and at a disadvantage, which enhanced its range and visibility. Betting on this strategic articulation gave it greater strength than the defense of the rights of each one separately.

Some lessons

If a main value of the Code has been that of mirroring the real diversity of Cuban society, one of the consequences of the consultations and the referendum has been to bring to the surface the discrepancies, criteria and feelings of the citizens who coexist here and now, including “the dark side of their hearts,” the one that remains outside the blind eye with which the radiant discourse on “the Nation” is often constructed.

By taking it to consultation and then to a referendum, a basic premise of democratic functioning was put to the test, first and foremost: to guarantee space to say things without fear.

The consultation in 79,000 neighborhood assemblies gave space to those who defend, for example, the right of parents to “slap their children from time to time,” “because I was raised that way, and I appreciate it.” To ensure that “I have nothing against homosexuals, and their right to do what they want among themselves, and within their homes, but letting them raise children as if they were their parents, I don’t think so. What example will they want to imitate?” To oppose public education, arguing that schools “have no right to give children sex education,” as if it were a novelty. I was able to hear statements like these in consultation assemblies, based on “what the radio from abroad says,” and accompanied by the confession of “not having read the Code.”

If it is a question of change and civic education, I wonder how to intervene in a society that harbors beliefs like these, if the space for them to manifest is not provided. It is like wanting to dominate a bull without letting it enter the ring, saving yourself the part of dealing with it, and pretending that this is bullfighting.

Naturally, having a mechanism of direct democracy such as the referendum does not entail avoiding the functioning of representative bodies, of schools and organizations, of the community, of a public sphere where the issue of equal rights is played out in a participatory way. The Code is not just a point of arrival and a social conquest, but a major step in the direction of that change.

Naturalizing the discrepancy in those bodies, in those below and those above; calling for public debate, the exercise of government with transparency and making use of digital media to maintain communication between leaders and citizens in permanent consultation, and without waiting for the next referendum, are key to renovating politics.

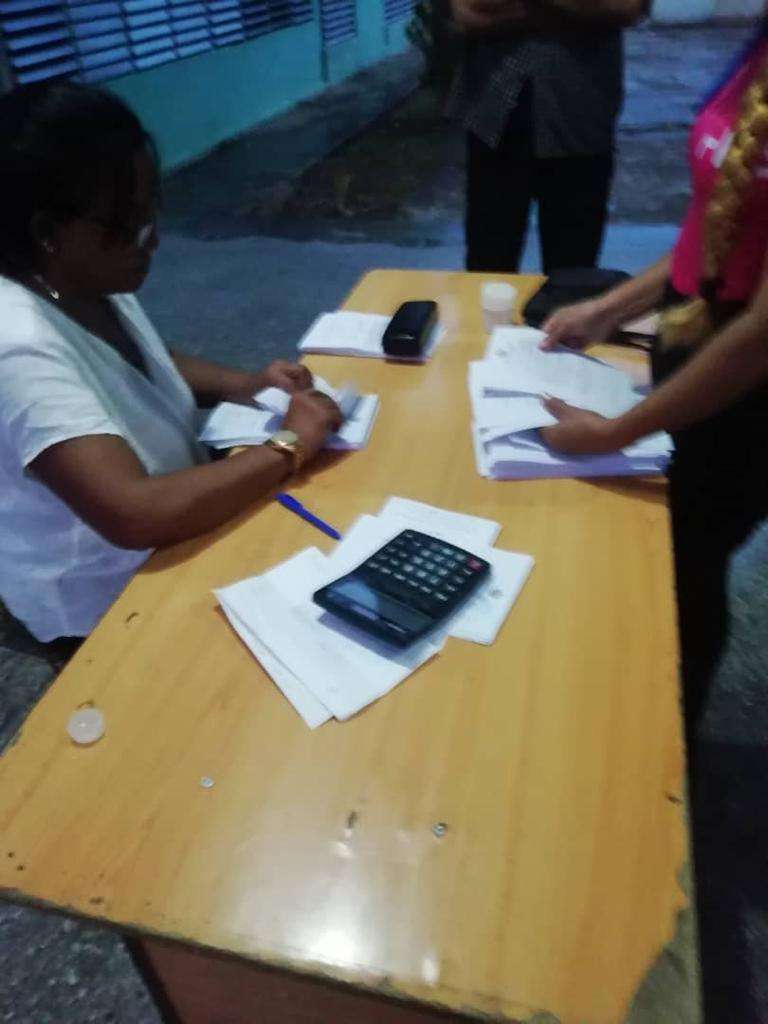

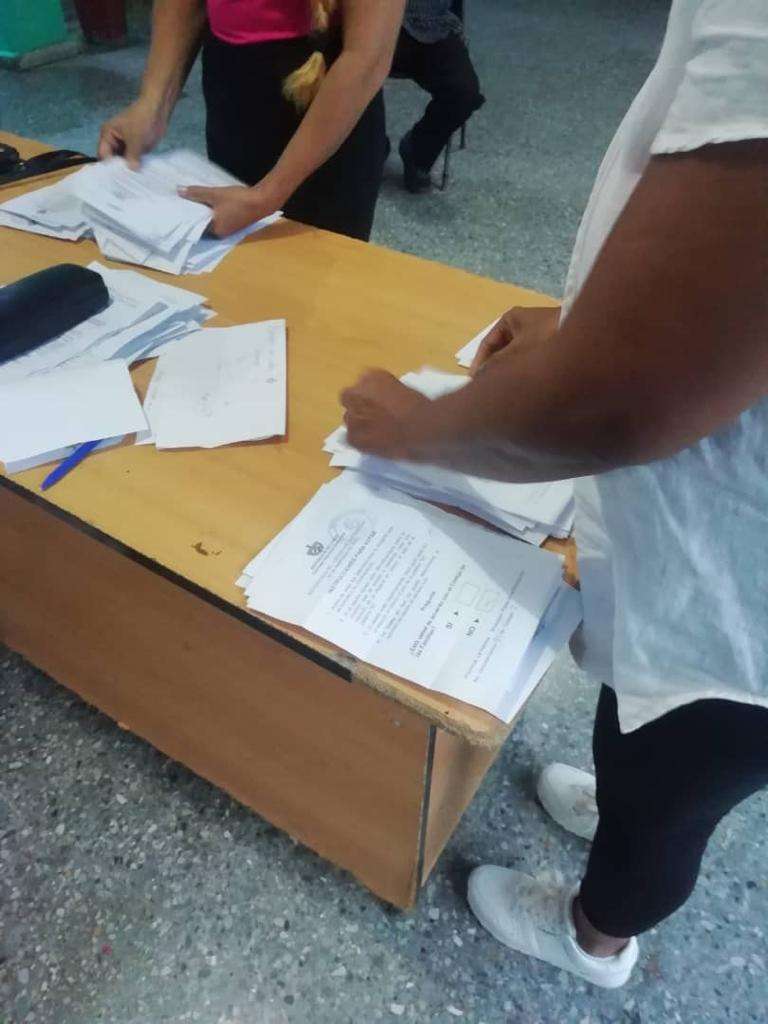

Going back to the referendum of the Swiss that I mentioned at the beginning, on same-sex marriage, they voted 64.1% YES and 35.9% NO, almost exactly like in my constituency, where some neighbors and I were able to witness the vote counting. The null and blank votes among the Swiss were 1.78%; in my area, 5%, including one who put Yes on the ballot, and added below “Look how good this idea of voting for the Code has been,” thereby invalidating it.

Of the entire Swiss electorate, 52.6% went to the polls. In my area, according to my calculations at the start of the count, 73% of registered voters had voted (this time with a pen). When the results of the vote in the Swiss Confederation were announced, the conservative opposition reacted with the premonition that “the floodgates had been opened to any number of dangerous practices.” LGBTs celebrated that “it was a historic day, a big step forward that they had been waiting for years.”

Now that we are part of that select group of countries that have achieved such advanced civil rights legislation, it would be possible to learn from what we can do better. To realize that interpreting the Yes in this referendum as a vote “for the Revolution and socialism,” or the No as its negation is basically the same approach that politicizes everything in the worst way, shortsighted and simplistic. That replicating the same theme, at the same time, through each available means of communication, and repeating slogans, produces a counterproductive saturation effect, overwhelming even for sympathizers. That political education and the production of ideology in the 21st century is an exercise in intelligence and imagination, where whoever manages to extract and enhance the best of a political culture that also contains alienations and atavisms wins. That it is necessary to govern trusting in the citizenry, without idealizing it, and at the same time, without treating it as minors.

If, in spite of everything, the families’ referendum reached those results of participation and approval, we would have to claim, like Fito Páez, who said that everything is lost? Although this “changing our house will not be as easy, nor as simple as it was thought.” And although in our case, it is not just for “just changing.”