He swung the machete like the branches had offended his mother. We are climbing the hill to the top, where the huge cave, la Casa del Cimarron, yawns into the thick forest. Before coming on this trip, Gustavo Arnavat, founder and chairman of the Cuba Foundation, repeatedly told me, “I want my own machete.” He said it jokingly, I think, referring to the logo designed by Miguel Barnet as the symbol of the Camino del Cimarron, but here he is, swinging that machete like it is part of his arm. Making the camino al andar.

It is day four of the eight-day, non-trekker-friendly version of the Camino del Cimarrón. The Camino del Cimarrón is a 350 km trekking trail that starts in Sagua la Grande, in the Province of Villa Clara, and ends in Cienfuegos. I created the trail by walking the distance in 2016 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the publication of Miguel Barnet’s Biography of a Runaway Slave (Biografia de un Cimarrón).

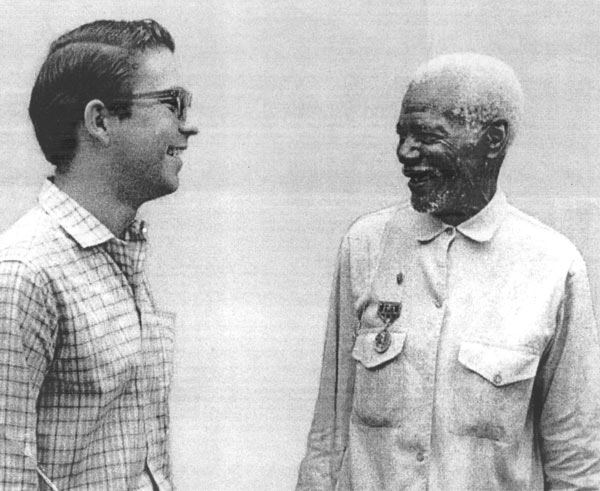

I designed the route by mapping the most significant places in the life of Esteban Montejo, the last surviving cimarron in Cuba. He recounted his life to Barnet during the years of interviews before the publication of the book. At the time of its publication in 1966, Biografía de un Cimarrón was as much a political statement as an anthropological or literary one.

In literary circles, the work set the standard for the testimonial novel, a genre that empowers those whose stories had traditionally been told by others. As a work of ethnographic anthropology, the life of Esteban made clear how slavery and freedom from slavery presented equally challenging threats to survival for a Cuban of African descent. Politically, the book provided a narrative in the voice of the previously powerless. As Graham Greene said, “There has been no book like this before and it is unlikely that there ever will be another like it.”

I suppose Greene was right. Fifty years later I saw in the biography of Esteban’s life the history of Cuba played out in his personal geography. Colonialism, slavery, the social and economic domination of sugar, the fight for independence and the neo-colonial distortions, all are dimensions of Esteban’s extraordinary life. The towns where he walked and worked are still where he left them. I set out to put this extraordinary biography into the geography of contemporary Cuba; to offer travelers a glimpse of the contemporary continuity of centuries of struggle.

Engine of Economic Development

From the beginning, I saw the trail as a potential engine of economic development for the towns and bateys along the way. Travelers searching for an experience off-the-beaten-tourist path will be able to see the Cuba por dentro where tourism is a rumor rather than a reality.

I had seen what had happened to the small towns along the Camino de Santiago in Spain from the 1990s, when I was one of only five or six thousand trekkers covering the 800km distance from the Pyrenes to Santiago, until now, when hundreds of thousands cover the distance every year. The towns grew. Some grew a great deal. Their populations grew, rather than migrating to the nearest urban area.

The Camino de Santiago made a difference in the lives of rural communities and their inhabitants. Since not all pilgrims stop at all towns, hard numbers are difficult to find but those who study the impact of trails on local economies agree that the smallest towns benefit the most from the creation of cultural trails. That is how I saw my walk back in 2016: as the first steps in creating a cultural path that would encourage “slow tourism” along regions that seldom benefited from the largess of tourist.

I realize that it is extremely unlikely that the Camino del Cimarron will become another Camino de Santiago, but that kind of traffic is not required for this Camino to benefit the rural towns along its path. And I am also aware that to make this happen, I would have to condense the walk into a more manageable format. There is a thriving culture of long-distance walkers in the world but to make the Camino attractive to most travelers, it would have to be packaged as a walk/ride tour that would offer an off-the-beaten-track experience while lowering the bar of the physical and time requirements of a long-distance trek.

Making this vision a reality was not easy but after years of persistence, we have now taken the second step. With the help of Daiquirí, an Italian travel company working in environmental and ecotourism in Cuba, we designed an 8-day tour of the Camino del Cimarron. Part walk, part ride, the itinerary follows the trail I blazed and stops at some of the towns that were most significant to Esteban in his life as a cimarron, a free worker, a patriot, and a citizen of a new nation. An intrepid group of travelers—a group of Cuban Americans and Cubans living on the island– braved the June heat and rains, the apagones and the search for combustible to help shape the Camino del Cimarron into a cultural destination worthy of others who want to see and contribute to the lives of those living in Cuba por dentro. All of us were aware of the extreme difficulties currently facing the Cuban people. And all of us hope that developing the Camino will alleviate some of the difficulties for some of the people.

Here are some of the highlights of the trip.

Day 1: Havana

We began the tour in Havana, although the Camino starts in Sagua la Grande, because, as it was explained to me, if travelers come to Cuba, “they want to see Havana.” We met with Miguel Barnet at the Fundación Fernando Ortiz, and he spoke, with excitement, as if it were the first time, of Esteban, the book, how it came about, its impact. A tour of Havana included the usual tour of the historic plazas and structures as well as an introduction to the experience of Afro-descendientes during the colonial era. We had the opportunity to attend a conference by the inimitable Emilio Cueto on the impact of Jose Martí in the world. Although initially I resisted starting in Havana rather than Santa Clara, the day allowed the participants to establish a framework of Cuban history and its relationship to the colonial exploitation of slave labor.

Day 2: Sagua La Grande

We arrived in Sagua the next day, ready to begin the Camino. Yadiel, the director of the Sagua museum met us at the Hector Rodriquez, the sugar mill known as the Santa Teresa when Estaban was born in its infirmary. We walked to the barrancones.

“They controlled the slaves by having only one way in and out of the courtyard which is, as you can see, surrounded by the sleeping areas,” he points around the rectangular space. The design and architecture remain. Some of the original bricks and wood beams are still part of the structures. The residents are workers, here at the Hector Rodriquez or wherever labor is needed nearby.

The infirmary is also in ruins. When I first came here with Miguel, tears came to his eyes as he saw what remained of where Esteban was born. “I didn’t know this place still existed,” he said.

We met a woman, Caridad, and her children, a thin woman nearing 70 whose ancestors lived in this same batey as slaves. She was the physical manifestation of historical continuity. She was hesitant to pose for pictures but drew her sons close did us the favor.

Day 3: Sagua—Mariana Grajales (Flor de Sagua)—Guayabo Cuartel—Remedios

An early wakeup call on day 3 and a quick ride to the batey of Mariana Grajales started us on the Camino proper. It took me hours to walk from Sagua to Mariana but we were there in thirty minutes.

Only a few ruins remain of the old Flor de Saqua mill, (renamed in the late 1990s after the mother of the Cuban patriot Antonio Maceo), as is the case for most of the mills that roared during the heyday of sugar production on the island. A grassy area now stands where the heart of the old mill stood. The smokestack juts skyward, a white monolith that begs for some 2001: A Space Odyssey background music. To the east of the smokestack, in ruins, stands the old slave quarters, the barrancones, the long room, shot-gun structures, over the years reworked into living quarters before decaying into ruins. Over two hundred slaves lived here during the time of Esteban. Still visible are the ancient walls and French tiles brought in by the owners who took over after the war of 1895.

He ran from here. From where we are standing now. Twice. They caught him “like a cochinito” the first time, tortured and shackled him. The second time he made it out, for good.

The once magnificent casa mayoral sits next to the baseball field on the west of town, in ruins. Locals call it “la casa francesa,” indicating that at some point the owner of the mill was of French origin.

We too have a Mariana in our ranks. Mariana Gaston, one of the historical figures in the long struggle waged by many of us in the extensive Cuban diaspora to incorporate ourselves into contemporary Cuban history. One of the creators of Joven Cuba, a member of the Areito editorial group, and one of the founders of the Antonio Maceo Brigade. Mariana has traveled to Cuba, since 1973, hundreds of times. Still, she has never been on a trip like this.

We walked down a sometimes shady dirt road from Mariana Grajales to Unidad, another batey that used to service a sugar mill back in the day. The six-kilometer walk took us through glowing fields of cane and sparsely populated cow pastures. Tocororos1 provided the musical background.

At Unidad, I asked the men sitting in the shade of a ceiba if any artists lived in the town. “We had a good artist,” said the one sitting on the ground, leaning back on the tree. “but he’s gone. Left.” We all knew he meant left the country. “But here comes the art teacher at our school,” he pointed with his chin at a thin young man in a white shirt coming our way. “He’s pretty good,”

The young man is an artist, “pero no tengo la academia.” And in town there is also a woman who weaves interesting boxes and wall art of straw and other materials. He gave me his number. “Next time a group comes, and I know about it, I’ll text you so that you can your friend can put out your work. Who knows, you might sell something to folks like these,” I nodded behind me where my troupe rested and drank water under the ceiba talking to the townspeople.

One of our intrepid travelers is the famed photographer Julio Larramendi. He is busy taking pictures of the people and places. He pointed the camera at three children playing in the street while the mother talked on the phone. One kid saw him and ran towards his house. “Mama, change my clothes. There’s a man taking pictures of us!” Erick, the designer par excellence of our project website, is capturing it all on camera.

The waiting coche de apoyo took us to the foot of a small hill leading to the hacienda of Fernando Yanes. When I met Yanes, during the first walk, he told the tale of his ancestor, Pedro Yáñez. According to Fernando, Pedro “had slaves. Four or five women and a couple of men. The property was pretty much the same, maybe bigger, going down to the road. I think he had some sugar down in the flat lands and tobacco up here. Two of his slaves took off one day and became cimarrones together. Yáñez figured they’d head to some palenque nearby, but they didn’t even get that far.

“Yáñez and his crew caught them… and tied them up at a stone well down there,” he motioned with his chin. “Shackled them by the ankle and had them pull water out of the mill below all day. They pulled water up from the well all day and all night if needed. Water headed to La Central Dos Amigos.”

Yanes on this trip is older and mellower. He welcomed us, told stories about his life and history and fed us roast pork and congri. We roamed the sprawling granja and enjoyed the hilltop view. After a few hours, we descended the hill and rolled in the van towards Remedios, one of the first Spanish settlements on the island.

On the way, we passed El Purio and Vueltas, two towns important to Esteban. His first job as a free man was at the mill El Purio (now renamed Perucho Figueredo). His work routine did not change much from his experience as a slave but, he told Barnet, “they beat us less.” Vueltas is remembered by Esteban as a town run by bandits. Some bandits aided the mambis, others supported the Spaniards. All of them were vicious.

Day 4: Remedios and the caves—La Casa del Cimarron

Esteban spent a year in a cave to the east of Remedios, near the settlement of Guajabana, living off the land and raiding local farms for their cochinitos. The road leading to Guajabana was part of the Camino Real del Norte. According to historian Esteban Pichardo in his Caminos de la Isla de Cuba, published in 1865, in Esteban’s day, Guajabana was a waypoint on the major route for travelers coming from the East—from Moron and Yaguajay—to Remedios. Pichardo’s one-hundred and fifty-year-old description of the path captures its lost essence.

This road, called the Real del Norte, because it follows more or less the North Coast, is approximately 20 yards wide in the areas where it’s not limited by the savannah, and is well kept and useful for wheeled vehicles… [The road] is highly important, since so many other roads have relationships to it, and is serves as the trunk of those who lead to the various ports of its extensive coastline, deserving to be classified as a road of the 1st order.”

That was then. Now, the road is a terraplén; a collection of potholes connected by hard dirt that makes driving a surgically precise procedure. It takes us over 40 minutes to travel ten kilometers and arrive at the foot of the hills where the “Casa del Cimarron” yawns open.

We follow the path upward, through a discarded quarry that provided the raw material for the rockbridge (pedraplén) to Cayos Brujas and Santa Maria. Low shrubs and tall trees border the path for a few hundred meters before it breaks out into a clearing and the altitude becomes evident. To the south, the well-defined rounded hills in the direction of Placetas and Santa Clara jut from the flat plain. The Florida Straits, sparking sunlight, and the white stone buildings of Caibarien are visible to the north and the cayos beyond.

This is where Esteban must have seen the ocean for the first time. It is clearly visible beyond the canopy which served as his patio for a year and a half. He spoke of the ocean as a big river and as a mystery of nature. Something that he could never understand. But he understood its power. The ocean, he said, can “carry men off, swallow them, and never give them back.”

“La Casa del Cimarron” erupts out of the forest and, once visible, it is all the eye can see. There is no path around it. Going in is the only way out of the forest if you do not want to backtrack. It is as if the forest has a mouth.

The cave is notable, says Alexis our guide, because it is the only one in the region that has an entrance on both sides of the mountain.

“It goes all the way through,” he says. “Like the river that formed it.”

Esteban Montejo didn’t know about the other entrance. The darkness and uncertainties it shrouded kept him near the light he knew, even if he shared it with snakes, the eternal majas. He was afraid of being trapped in the throat of the mountain, in the dark, with no way out. He was curious to search for another entrance, he told Miguel, but with no light to explore its insides, he never ventured into the darkness long enough to make it to the other side of the mountain. He lived near the entrance vault and used it as a base from which to hunt and scavenge.

We walk through the cave with our flashlights. Our shuffling disturbs the bats. Esteban remembered the bats in the cave as living in total freedom, since they had no natural enemies. He remembered walking on the soft mattress formed by the guano on the cave floor. I notice its softness as well, like walking on memory foam. Bat guano is highly flammable, as Esteban discovered one day when he lost control of his cooking fire, and the inside of the cave burned like a fireball.

Not far from the Casa del Cimarron, on our way down the hill, Alexis leads us to another cave, La Cueva del Obispo. The Bishop Espada y Fernández de Landa supposedly discovered or named the cave back in the late 19th Century. A camouflaged gaping hole in the mountain leads straight down, following the thick roots of trees that provide a rustic staircase into the darkness.

The sunlight shines into the cave just enough to get you into trouble and then goes from dim to none within a few feet of the entrance. But the inside is majestic. Our lamps illuminate an underground natural mural; beautiful soft rock water formations left behind by the river that ran through here millions of years ago. Orange, red, white, black swirls and layers of various thicknesses. We were looking at the memory of the mountain.

Back in Remedios we toured El Museo de las Parrandas and rode the old steam engine train to the Museo de Agroindustria Azucarera Marcelo Salado in Caibarién. The director of the museum, a man who spent his entire life, like his father and grandfather, working in this now-defunct sugar mill, led us through the history and practice of refining sugar. Sugar formed the core of his life. Now it was gone. We felt his nostalgia and sense of loss.

The rains came and we did not visit the church, a regret that will not be repeated in future groups. Even if for only five minutes, anyone visiting Remedios has to walk inside its splendid cathedral. Its 16th-century roots and 18th-century renovations make the church one of the jewels of Cuba. The gold altar and the statue of the pregnant Virgin Mary make the church unique. It was declared a national monument in 1949 (Remedios received the honor in 1980).

Day 5: Remedios—Viñas—Zulueta—Placetas—Santa Clara

Julian Zulueta was a Spanish marquis and a Cuban slaver and sugar magnate. He owned several sugar mills in the region. On the fifth day of our trip, we walked 6km on the ghost of a railroad line that he had built to transport the sugar from the mill Zaza to the port of Caibarién. The line starts in Placetas at a downhill angle so that no energy is required to move the train down the tracks to the port. The steam engine lights up on the way back to the mill with empty wagons. The water tank that fed the engines still stands and we pass it on our walk.

Behind the water tank is one of the many fortins erected by the Spaniards to guard the transfer of sugar throughout the island. Maribel and her family live next to the fortin on a property that they’ve owned for generations. A row of passive solar panels on the side of the house provides shade for four sleeping piglets. She offers us fruits and water and a chance to watch her men make coal out of marabú. It’s a grueling process but if done right, the coal will sell well throughout the region.

We walk the remaining two kilometers to Viñas and devour our box snack before getting in the van and driving to Placetas. On the way we pass the mill Chiquitico Fabregat, known as the Ariosa when Esteban worked there, and through Zulueta, one of the many towns where Esteban looked for action after work in the mill. He was a restless loner, Esteban. A cimarron from birth, he confessed to Barnet.

The surprisingly well-preserved structures of Julian Zulueta’s sugarmill the Zaza sit on the outskirts of Placetas. The mambi army, led by Maceo and with Esteban in its ranks on its way westward to encounter the Spaniards at Mal Tiempo burned part of the sugarcane fields feeding the Zaza but the core of the mill—its barrancones, infirmary, casa mayoral and the church remain varying degree of preservation. Local guides make the slaver Zulueta sound like a regular Joe as he built an empire based on slaves and sugar.

The main problem that we encountered in making the Camino del Cimarron accessible to a general audience is the absence of adequate hostals along the route. We could find no hostals in Placetas with adequate “condiciones” to house paying travelers, so we rode to Santa Clara were casas particulares abound.

Day 6: El Copey—Guaracabulla—Mal Tiempo—Central Caracas—Cienfuegos

The drive from Santa Clara to El Copey, the start of our 15km walk, took thirty minutes. By 6:15, as the sky began its transformation to blue, we were at the trailhead, an overgrown path behind a row of houses just off the Carretera Central. From here we followed the GPS laid down by my first walk and cut campo abierto for four hours, through beautiful scenery that captured the essence of Cuba por dentro. Pastures, forests, guajiro farms with their oxen in the distance, flowers and butterflies everywhere. “It’s beautiful,” said Gustavo as he took a photo of a herd of horses in a pasture stretching to the horizon. “You can’t make this stuff up.”

Guaracabulla is said to be the geographic center of Cuba. Let us ignore the voices that argue the point for the moment and enjoy the giant ceiba that marks the center of our island.

At the Casa de la Cultura, Roman Peraza, a gifted decimista, welcomed us. The Decima is a ten-line poetic form, often improvised, which is a staple of artistic expression in the Cuban countryside. Roman is a repentista, a poet who improvises decimas. It is a spoken word performance inspired by the moment. After several minutes of poetry, Roman stopped and pointed at the group.

Brindo mi noble expresión

De forma muy elegante

Para darle al caminante

La ruta del cimarrón

Hoy recibí un alegrón

Un feliz amanecer

Porque querer es poder

El caminar da energía

Disfrutando la alegría

Junto a Guillermo Grenier

The riding to the monument of Mal Tiempo along the Carretera Nacional moves us quickly past three towns that I crossed on the walk: Matagua, Jorobada, Potrerillo. Choices must be made when transforming a two-week trek into a week-long experience, so the flatlands between Guaracabulla and Mal Tiempo were sacrificed.

But there is no skipping Mal Tiempo. On December 15, 1895, rebel troops, headed by Maximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo, entered the region of Cienfuegos. Esteban joined the group further east, sometime around the third or fourth of December. They met a resisting Spanish force of about 2,000 at Mal Tiempo, defeating them in what turned out to be a critical battle in the westward movement of the rebel army.

In the flatlands of Mal Tiempo, Esteban fought alongside Antonio Maceo, the Bronze Titan, second in command of the liberation forces warring against Spain, and Maximo Gomez, the Dominican-born Major General who headed the Cuban forces. For Esteban, the battle was a defining moment:

When we got to Mal Tiempo, Maceo gave the order to fight face-to-face. And that’s how it was done. The Spaniards, from the moment they saw us, went stiff all over. They thought we came armed with short carabines and Mausers. But, shit, what we did was take some shafts of wild guava and carry them under our arms to scare them. They went crazy when they saw us, and they threw themselves into the thick of it, but the fight didn’t last long because at almost the same instant we started to chop off their heads. But really chopping them off. The Spaniards were scared shitless of the machetes. They weren’t afraid of rifles—but machetes, yes…. Mal Tiempo was necessary to give courage to the Cubans and to give strength to the revolution. Anyone who fought there left convinced he could face the enemy… Maceo was certain of victory. He was tougher than a hardwood tree.

The next stop was the Central Caracas, one of the major mills of the 19th Century that is still active. The Central Caracas, owned by Tomas Terry, was one of the largest sugar mills in the world. It boasted the best technology, imported from the United States and Europe, of the 1860s. It was the first mill in the area with electricity, Esteban remembered. The manor house where Terry lived when in town barely stands, in ruins, on the grounds outside the mill, projecting the shadow of what it once was.

Terry, of Venezuelan origin, is a poster child for the multi-national Cuban slaver/ millionaire of the day. He made most of his early money by recycling slaves–buying sick slaves, nurturing them back into working conditions and then selling them for a hefty profit–and by extending credit to Cuban planters at exorbitant interest rates. Yet Esteban spoke well of Tomas Terry, remembering him as a cultured man who harbored the supremacist, colonialist ideas of the period but who established good relationships with the workers. He provided resources for the congos to establish two cabildos, one in Cruces and one in Lajas. Estaban visited them and remembers that a picture of Tomas Terry hung on the wall of the Cruces cabildo. Terry’s wife brought the statue of San Antonio in the Lajas cabildo from Italy as a gift to the practitioners, many of whom had worked at the Caracas mill before emancipation.

Day 7: Lajas–Ciego Montero—Palmira–Cienfuegos

The night was spent in a beautiful casa particular in Cienfuegos and in the morning a relatively quick ride back to Lajas put us on the Camino once again. Santa Isabel de las Lajas is best known for being the birthplace of Benny Moré, El Barbaro del Ritmo and one of the iconic Cuban singers of the mid-20th Century.

Lajas also belongs in our story of the cimarrón. Esteban worked nearby after leaving the Ariosa.

After the war, Esteban settled here and began to criticize the injustices he found in the newly independent Cuba. The discrimination, the fear and the exclusion of black participation in politics and civil society, all made him question the reasons why he and many of his brothers in slavery had sacrificed their lives to help give birth to the new republic.

He lived in Lajas at the same time as Coronel Simeon Armenteros and other members of the Partido Independiente de Color, the national party leading the revolts and took part in the 1912 revolt protesting the exclusion of blacks from national political culture.

Most of the violence of the uprising took place in eastern Cuba, around Santiago, but a few bands of Independentistas stirred the pot in the Province of Santa Clara; one group attacked the northern region around Sagua la Grande and the other, led by Armenteros attacked the communication infrastructure of Cienfuegos between May and July 1912. Esteban was in this group. The uprising was quickly crushed. Esteban survived to tell the tale.

The terraplen that leads to Ciego Montero from Lajas was impassable for the van so we drove the long way to the town whose name is plastered on just about every soft drink and bottled water sold on the island. There we met with Francisco Carbajal, a painter and educator who runs the community project “Con La Luz de los Colores.”

For the last twenty years, the Proyecto Communitario has worked with young people in the area to stimulate their artistic expression. Carbajal and his mother have transformed the entry room of their simple house into a gallery to exhibit the work of community artists. The work of one of the luminaries of the project, Tahimi Damas, is highlighted in the gallery. Tahimi passed away in 2022 but her artwork remains a testament to talent and perseverance. Tahimi was severely handicapped and from her wheelchair painted exquisite figures, alive with color and contrast, with the brush held in her mouth. I met her when I first passed through Ciego. She remains an inspiration.

The short ride to Palmira leads us to the Museo Municipal. The museum is a treasure trove of information about the creation and maintenance of the Afro-Cuban traditions in the province of Cienfuegos. Palmira, with three cabildos and two casa templos, is renowned as a mecca of Afro-Cuban religions on the island and the permanent exhibits of the museum emphasize this tradition. Santa Barbara in full regalia, the ritual drums from a local cabildo, the jewelry of the orishas are among the items on permanent display.

We were treated to a jaw-dropping dance performance by a troupe of young interpreters of the lives of the orishas. I have seen many such presentations but this one was exceptional. The stories of Yemaya, Obatala, Babalu-Ayé, Ochun and Oyá played out in the movements but also on the faces of the dancers. “Se les monto el santo!”

The last night in Cienfuegos was spent at a surf-side restaurant, admiring the sunset over the Bay of Cienfuegos and sharing thoughts on how we could improve the prime-time version of the Camino del Cimarron.

We all reflected on the warm and thankful welcome we received in all towns along the way.

This was Edmundo Costa’s first trip to Cuba since leaving the island with his parents in the early 1960s. He called the tour “a momentous trip.” His family lived in Havana and he thought it unlikely that even they had seen Cuba por dentro. His open mind and creative recommendations enriched the experience of all on the trip and will contribute to improving the experience of future travelers.

Gustavo, the machete wilding trailblazer, put it in a way that all participants could understand. “It was such a transformational trip for me. Tenemos que seguir pa’lante!”

Tip: If you’re interested in learning more about the Camino del Cimarron, contact us through our website, Caminodelcimarron.com.

Julio Larramendi is organizing a tour for photographers in November (18-26), which includes one additional day in the Escambray.

“Photographers don’t walk,” he laughs, “But the visuals on this Camino are outstanding!” Daiquirí also is organizing an open group for travelers interested in experiencing a Cuba that tourists seldom see.

Notes:

1 Tocororo is Cuba’s national bird.