She comes from a Santiago de Cuba family keenly interested in art and the humanities. Her father, Horacio Maggi, was a painter, furniture and interior designer, cartoonist, teacher at the San Alejandro Art School and at the National School of Design.

On her mother’s side, Rosalía Holland, there are many musicians and professors in different specialties.

She is the niece of renowned teacher Beatriz Maggi and cousin of designer Maggie Holland. Just to give some details.

Horacio, her father, studied Mining Engineering in the United States. When World War II began, he enlisted, along with his classmates, in the U.S. Army. He spent the war in Europe, in a unit of sappers. During a leave, he traveled to Santiago de Cuba, and there he was surprised by the end of the war and love, as he met Rosalía, who would be the mother of his six children.

The couple settled in New York, because Horacio thought it was the ideal city to start his career as an artist. Jacqueline was also born in the Big Apple. She is an artist notable for her versatility and for the balance that her works present, between the density of the concept and the visual packaging.

We talked with her.

When did you travel to Havana for the first time?

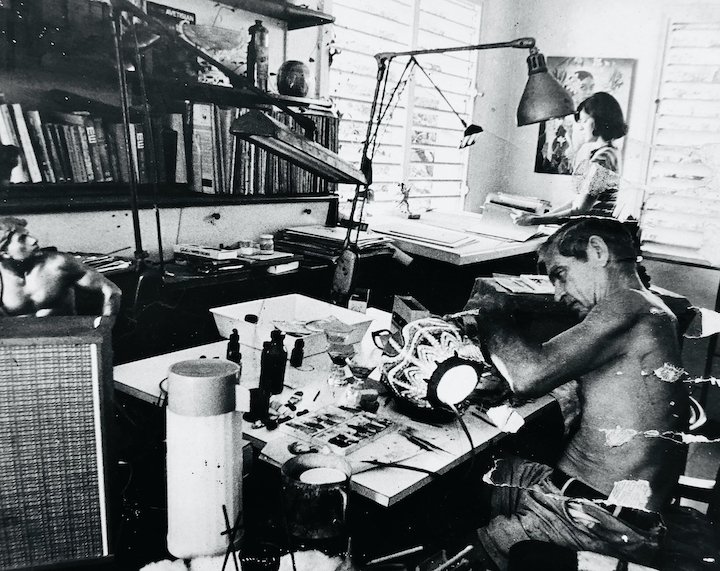

Although I was born in New York in 1948, Cuba is mine, as it is for all Cubans. I don’t remember anything from those New York days, only stories and photos remain. In that apartment in Chelsea, my father, my mother and I lived with the studio and the art materials with which my father worked as an architectural and interior designer. Something must have impregnated me that would never leave me. From then on home and study have always been together, and wherever I have lived, and to this day, I have not been able to separate them. I was just over two years old when the family decided to return to Havana, so my first memories are those of Havana in the 1950s, always near the sea.

I am Cuban because the place and circumstances of a birth are fortuitous events. Nobody or almost nobody in the Cuban and international artistic community knows that I was born in Chelsea, everyone recognizes me as Cuban, not as a “yuma” (Cuban slang for American).

You studied here (in Cuba) and then you were a teacher, you joined the cultural life of the country. How was the learning experience?

My father was my first teacher: techniques, work and passion. And I spent many of the best moments of my childhood and youth in his studio. When I was growing up, I had dreams of being an architect, interior designer, and children’s book illustrator. I finished high school and went directly to the National School of Design (which preceded Higher Institute of Design) to study the specialty of Graphics. I graduated in 1972 and started working as an illustrator at Pueblo y Educación publishers. But in 1976 the Higher Institute of Art (ISA) was created, and another phase began. I enrolled in 1977 in the course for workers, in the specialty of Engraving, of which I knew nothing and learned a lot.

They were intense years, in which I did juggling: marriage, motherhood; working in the publishing house and running to the ISA, to the Experimental Graphic Workshop, learning again, new colleagues, in the hive that was that inspiring space. Those were the times to integrate myself to the dynamics of plastic arts, to participate in many national and international exhibitions and to win prizes.

And then another cycle begins. I decided to leave illustration and start teaching at the National School of Art (ENA). It was never my purpose to teach, but teaching has come to occupy a large part of my life, until today. I taught printmaking at the ENA for 10 years, from 1982 to 1992, and I enjoyed it, especially because of the exchanges with those young people who came with great illusions and desires to learn, to discuss ideas and transform the country through art. We tried to do everything in the midst of many shortages.

In my classroom, from the door to the inside, the least I taught was engraving, because I myself questioned the limits between the manifestations and the need to go beyond them. We talked about literature, about the subjects that interested the students, about what we saw, about transgressing manifestations…. My first installations are precisely from those years, where I convert the matrices of my engravings into sculptures and three-dimensional spaces. Some critics have said that I was a pioneer in this, I don’t know. I am happy to follow many of my students, such as Alexandre Arrechea, Dagoberto and Fernandito Rodríguez. I am glad to hear about their lives; I celebrate their successes. I am still by them in many ways.

All my life is linked to Cuba, my training, my fellow students, fellow artists, my family, love relationships, and this is what has marked my identity.

Do you maintain ties with Cuba?

I maintain all kinds of ties with Cuba: with those from my generation who have stayed there (there are fewer and fewer), with my relatives, with many young artists who live on the island and who move around the world producing from anywhere; with colleagues from the intellectual community who also live there and travel everywhere; with the art that is produced on the island or outside of it; with purely Cuban spaces and with the sea that, far from separating us as an island, unites us with the world. I go to Havana often, as much as I can. Although I have never left, because Cuba is not a geographical latitude but a state of mind. Anyone who does not understand that will continue to live in a cultural ghetto and, sadly, in a single ideological dimension.

How was your insertion in American society?

Gradual, progressive. I started from scratch. I had the advantage of being an American, but with the disadvantage of the deficit of something that was not taught in art schools in Cuba: how to deal with, locate and survive in the maelstrom of the art market.

This process began in 1993. The worst thing was leaving my daughter, grandchildren and family in Cuba for a while. But I was alternating here and there, which made my existence less painful. I had many family members in New York, and Jadite Gallery, from NY, began exhibiting my work for several years. But, in the mid-1990s another new moment happened: I did my last personal exhibition at Galería Habana, in 1999, and I settled in Washington, D.C. The four seasons teach you the virtues and the need for changes and regeneration.

In 2000 I returned to teaching thanks to the invitation from Peggy Cooper Cafritz, the great American cultural promoter, collector and activist, who learned about my work during a visit to Havana in 1999, and asked me to become a teacher at the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, D.C., of which she was the founder. And I have to say that I also owe that to the prestige of artistic education in Cuba, to my experience working with my Cuban students and to my own work, developed in Cuba.

The Duke Ellington is a prestigious school, similar to what the ENA was, with the same enriching coexistence between manifestations: theater, literature, dance, visual arts, music, and that detects and develops the talent of young people belonging to minorities and social groups that by other means would not have been able to achieve artistic training and insert themselves into the American mainstream, as they have effectively done. Many have been my students and today they are acting figures that make me proud. I am still part of the academic staff of the school.

We know that identity is a construction, the sum of several identities. How have you built yours?

I am the same Cuban as always, only that I have walked more roads, discovered twists and turns: I am my tools. The sorrows and the joys, the loves and heartbreaks, the discoveries, the ideas shared or not. I am a mother, grandmother, teacher, doer and always a learner. I am satisfied to feel multiplied in my students here and there, and even in my granddaughter, who has just graduated from her art career in New York. It is like going back to the seed.

Do you dream of Havana?

I don’t dream about it, but I think about it, and it hurts. I want a better Cuba for all Cubans and I am aiming to achieve it.

How to define your poetics?

I learned to do with my hands what I could, with what I had and where life would take me, and so I will continue. And I would tell you that I do not scream, rather I whisper.

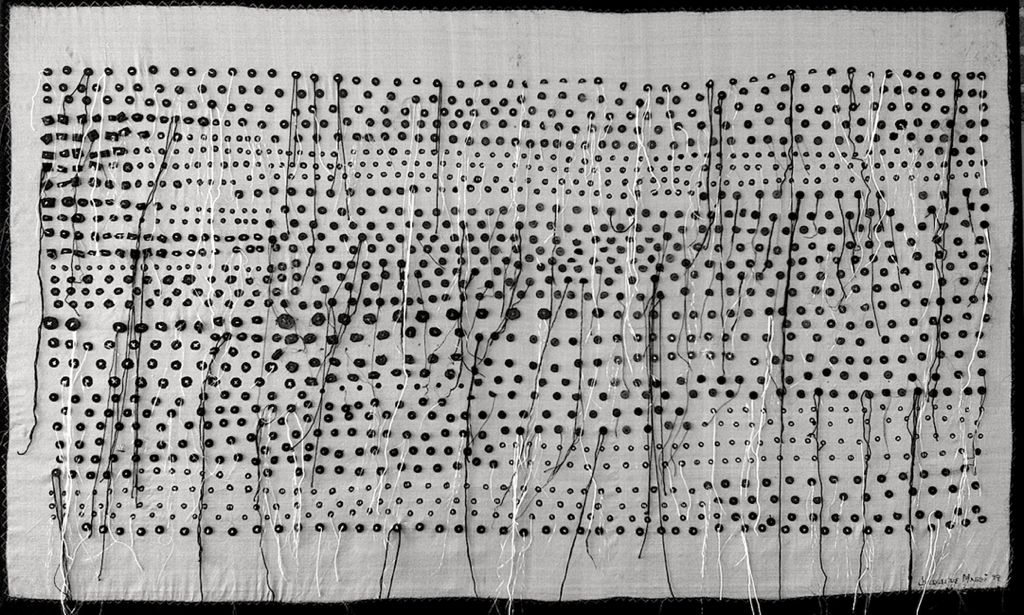

For years I have moved between various techniques and materials. Engraving, sculpture, drawing, textiles, installations…. Sometimes I create small works, and at others large-format works, with or without colors. The human figure rarely appears, because it is implicit.

But what’s most important are the themes that have obsessed me throughout all these years: the transcendence of the simple, of the everyday. Although at first glance they seem light themes, I insist on my inability to deal with the domestic environment, with frustrations and gender clichés. A first look at my works, from the end of the 1980s, when I carried out some exhibitions of an entirely installation format, they were already captivating due to the quality of the manufacture, the familiarity of the subjects and the apparent delicacy of the objects; but seen carefully, they are a summary of my nonconformities, which I manage to exorcise through the roughness of the materials, or the violence that artisan work implies when manipulating them.

And like Flaubert, I say: “One doesn’t choose one’s subjects, one suffers them.”

The last time I saw your work in person was in 1991. I am referring to the exhibition Cambio de estación, at the Castillo de la Real Fuerza in Havana. Thus it is very difficult for me to have an overview of your work. Can you outline an itinerary, describe the different stages of your work? Do you develop thematic series? Do you combine different disciplines in these series, such as drawing, painting, sculpture, installations?

There have been big and small leaps in my work. I was doing almost exclusively engravings for 10 years. I got an engraving grant for six months in Paris, at Atelier 17 of S.W. Hayter, a famous and prestigious workshop. Paris and the Atelier were a turnaround. When I returned to Cuba, I very sporadically did engravings. Then the period of woodcarving began, an almost infinite series to which I always return.

After the one-man show at the Castillo de la Fuerza, which I titled Cambio de estación, came times for several personal exhibitions in Spain and New York, with wood sculptures, installations, drawings, and paintings.

And then, again, my last exhibition in Cuba in 1999, Ajuares, at Galería Habana, also with ebony sculptures and installations that include works in xylography.

Everyday themes persist for many years. After some time here, in Washington, D.C., I had the opportunity to be a “student” again, and be fascinated with new materials and their techniques: metals, ceramics, textiles, and also larger formats. Curiosity kills me and I enjoy the processes.

What is the theme of the Refugio collection, made between 2019 and 2020?

I made my first “Refugios” when I arrived in Washington, D.C. They are reused building bricks that I find anywhere and that are really hard, difficult to intervene. The need for shelter, for a safe and permanent roof in Cuba had hit me so much that perhaps those bricks I found made me believe that I was beginning to lay my first stone of what would become my house.

But I started the real series in 2019 and it was no longer just about me, but about that huge and tragic migration that was unleashed across the Mediterranean and in so many other places, until today. I returned to the theme of that basic and ancestral need for the search for security. Going beyond the literal meaning: Shelter means so much more! Now I remember the words of the Master: “Son: Scared of everything….”

I see that your last exhibition, in Washington, D.C., is from 2003. Why haven’t you shown your work individually again?

I believe there is a time for everything. It is good to have personal exhibitions, they have their purposes and benefits, of recognition and commercialization. In recent times I have preferred to be more discreet and I have kept exhibiting in thematic group exhibitions. I maintain a systematic exhibition work with the Washington Sculptor’s Group, which brings together sculptors from Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. I have also exhibited in Miami, in Havana — at the event Detrás del Muro II —, and always with the Estudio Figueroa-Vives, with which I have been working for more than 20 years, and which maintains updated knowledge of my work from Havana. I have also made sculptures here (United States) for public art commissions, private residences and schools. I think it is time to return to an upcoming personal (exhibition). I’ll let you know.

What projects are you currently involved in?

I am in a moment of reconsideration, of a new “change of season.” The years make you look beyond, away from yourself and everyday issues, and you pay more attention to the hardships and beauties of our wounded planet and its people. I think that is where my new paths go.

I am interested in knowing more about Ms Jacqueline Maggi. The heading that precedes this says “obituary”. Has she passed away?

This is very enlightening in a multifaceted manner. It’s about the plastic arts. But it’s also about a soul which is wandering thru our planet and transforming it in very special and BOLD WAYS.

Jay M Castano

Wash. DC. Aug2025