Help us keep OnCuba alive here

Religion is no more the opium of peoples than the market dictating every possibility and meaning of life, or than structural corruption, political despotism, undemocratic impunity. If it it’s about humanity’s opium, the list is long.

Explaining the global conservative tide by claiming, without further ado, that “religion is the opium of the people” is politically sterile because it forgets the complexity of our societies and the legitimate place that spiritual worlds and faith―including religious faith―have for people and groups.

The process is more complex: we are facing the expansion and taking root of anti-rights neo-conservatism, both religious and secular. Within the religious framework, these neo-conservatisms translate into what analysts call fundamentalist actors. From other approaches, there is talk of reactionaryisms, anti-rights actors or fundamentalism. Although each categorization has its specificities, there is some agreement on some characteristics: the construction of rhetoric of enmity against others (there is an enemy of God, of the church), an absolutist and intolerant agenda against other positions (both religious and secular), a political use of religion, the imposition of its values, behaviors and forms of organization on the whole of society, the promotion of moral panic because of the horror of the present in sin and the future, the specification of a strong agenda against the rights of women and the LGTBIQ populations.

Cuba did not arrive too late to this fundamentalist concert that since around 2010 has been important in Latin America. But the matter is earlier. Since the 1960s, the domes of the Catholic Church and its most conservative wings have expressed themselves with a firm hand on sexual policy, beyond the ecclesial walls. Paul VI (1963-1978) and John Paul II (1978-2005) made official the opposition to contraception, homosexuality, women’s priesthood, and abortion (again), and made a loud and clear call to the grassroots to get involved in defense of that sexual morality in civil society and political society. The “integral Catholicism,” which came from before, also crystallized in apparently secular actors (including NGOs). They are part of the conservative tide that exists today.

At the same time, evangelical churches, especially Pentecostal and Neo-Pentecostal, grew between the 1960s and 1970s, and the “theology of prosperity” and the doctrine of spiritual war emerged. In the middle of the following decade, this evangelism was expanding in the large cities of the region. Conservative Catholicism, still playing a leading role, has had to start sharing a place with evangelisms, which are expanding their presence in grass-root communities, make their public voice audible and influence many political apparatuses.

The Action Plan of the 4th Population Conference―Cairo, 1994―and the World Conference on Women―Beijing, 1995―unleashed a conservative reaction. Shortly before Cairo, the document “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium” had been drawn up. It was signed by U.S. public voices from both religious wings and the document placed in parentheses the usual rivalry between Catholics and Evangelicals. The initiative was not recognized by the Vatican, but it had an impact. It was the basis for activism against sexual and reproductive rights, gender equality, sex education and the recognition of sexual diversities. Among its objectives was to answer the “existing laws against obscenity” and from there they proposed the strengthening of religious citizenries.

At present, conservative Catholics and Evangelicals have changed their repertoires of action, expanded their bases, focusing their agenda. Sometimes they act in alliance and sometimes independently. Systematic campaigns and mobilizations can be registered to curb comprehensive sex education programs, the rights of trans and gay people, and access to legal abortion. The re-traditionalization of families, the re-biologicalization of bodies and the religious moralization of the public sphere make up the matrix from which the contents of their agenda are specified. All the countries of the region are aware of this, without exception and regardless of the political sign of their governments.

Without considering the complexity of these actors, it will be difficult to ask focused questions and agile alternatives, with possibilities of audience and effectiveness beyond the circle of those of us who are already convinced that fundamental rights are not restricted, are not moralized, are not taken to a plebiscite; they are only guaranteed, expanded and enjoyed.

Visible issue in Cuba

The existence of anti-rights religious actors sufficiently robust to force the nation’s destiny broke into Cuban public spheres in 2018, in the heat of the popular consultation of the Constitution of the Republic that was approved later, in 2019. The apple of discord was the possibility of opening the door to egalitarian marriage. In the process, diverse actors were measured (which should not be understood straight out): faith communities that defend rights, LGTBIQ and feminist groups, organizations and institutions that defend rights, democratizing state voices, conservative state voices, conservative citizens without religious affiliation and anti-rights faith communities. The combination of the aforementioned three actors defined the pattern. Although the possibility was not canceled and there is still a chance in the Family Code to come, they conditioned the outcome to a referendum not yet consummated. And it was so, although it is a democratic doctrine that rights are not conditioned.

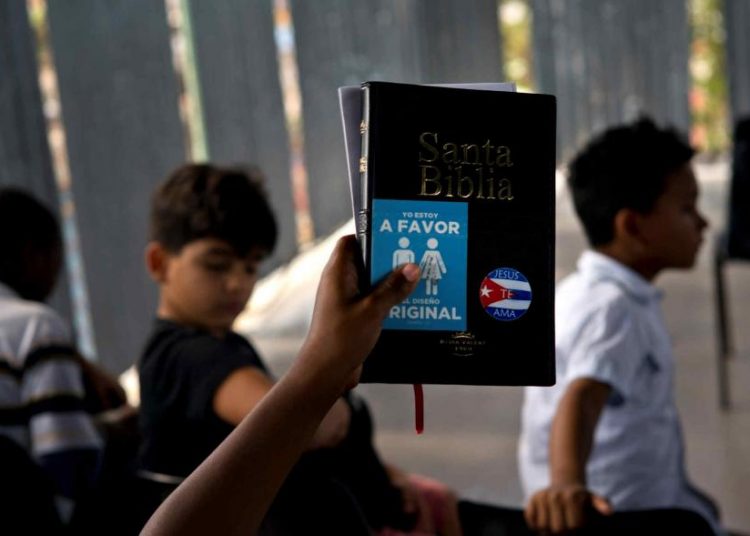

*Caption:

IN FAVOR OF ORIGINAL DESIGN

The Family as created by God

Genesis 1:27

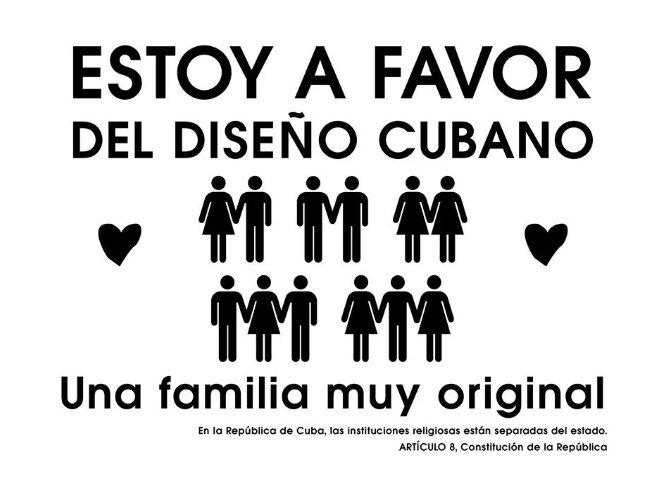

*Caption:

IN FAVOR OF CUBAN DESIGN

A very original family

In the Republic of Cuba, religious institutions are separate from the State.

ARTICLE 8, Constitution of the Republic

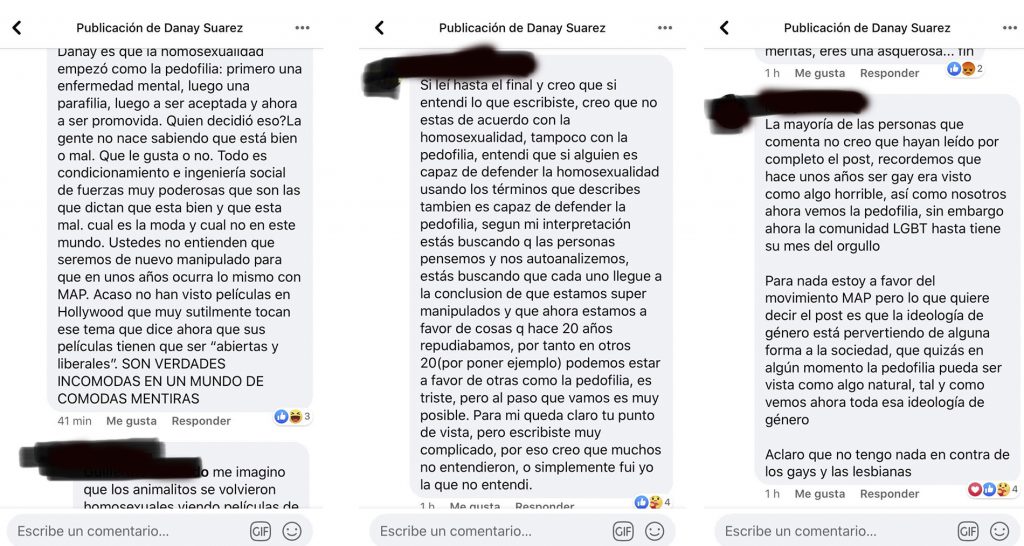

The subject has again become tense apropos a publication shared on social networks of singer Danay Suárez―evangelical, with a history of anti-rights statements. Suárez echoed a theme that has been on the social networks and Latin American media in recent weeks: the alleged existence of a group that seeks to legalize pedophilia and claims a seat within the LGTBIQ community. That this group does not exist as a movement that seeks to integrate into the LGTBIQ community has been verified, but the publication tried to demonstrate that, by using same arguments to approve homosexuality, pedophilia could be approved. The statement is sordid and anachronistic.

With thousands of reactions and comments, the publication in question zoomed in on anti-rights religious actors. The concrete fact is important, among other reasons, because it shows the reactive capacity of different voices (the same ones that were confronted during the popular consultation on the Constitution) and proposes a kind of general rehearsal of what will very soon be the staging of the referendum on the Family Code.

However, one should not confuse the part with the whole. Let us suppose that it is possible to deactivate, with judicial recourses and citizen response, those public discourses of specific persons. The achievement would be remarkable and it is necessary to join voices for it without forgetting, at the same time, that the underlying problem would remain firm: anti-rights programs gain ground in the offline neighborhoods and territories of a society that has already shown that it welcomes and feeds them.

In the online world that can also be verified. Of the thousands of comments to the Facebook post, most are critical of the argument reproduced by Suárez. But, it should not be ignored, others show support. Here are three examples (in Spanish), out of hundreds:

Other people claim that the post is not far from reality and is only trying to warn of the horrors to come. They speak of the supposed “gender ideology”1, they show respect for “an opinion that has logic.” “Many would like to have this value,” “the word of God is true,” “the document criticizes those who want to normalize the concept for homophobia, it is not an attack on the LGTBIQ community,” say others. This is the way people speak out giving support or listening carefully to the program behind the publication. They don’t always do it with religious arguments. Some declare that they are not talking about religion or politics, but about obligations to humanity.

Why have these religiously-based anti-rights programs expanded?

This is, without a doubt, a complex process. If we don’t get the foreground out of focus, we miss the main part. There are two recurring hypotheses to explain why these religiously-based anti-rights programs have expanded: 1) the imperial policy of the governments of the United States, which tries to deactivate, as in the Cold War, popular actors through fundamentalist religious alienation, 2) a kind of “fake conscience” of individuals and groups that enroll in anti-rights faith communities.

Uncle Sam

The thesis that the establishment of religious fundamentalisms is explained only because of American conservative influence does not express the complexity of the matter. There are national interests at stake and domestic constraints. However, Uncle Sam’s hand exists, acts and influences in all of Latin America and Cuba, trying to demobilize the popular sectors and/or bring about changes in governments.

The Alliance Defending Freedom, a U.S. conservative organization that has sued the United States Department of Justice to oppose advances in women’s reproductive health and the rights of the LGTBIQ population, is a training space for evangelical pastors throughout the region.

Ralph Drollinger, leader of the U.S. Capitol Ministries, plays a key role in American influence. That evangelical organization is operating within the White House (for the first time since the Donald Trump administration, although it existed in that country since 1996) to secure disciples of Jesus Christ in the political arena. In recent years, it has been established with representations in Paraguay, Mexico, Honduras, Brazil, Peru, Uruguay, Ecuador, Costa Rica and has announced openings in Nicaragua and Panama.

In Cuba, most evangelical churches have a “sister church” in the United States, from which they receive financial support. Journalist Tracey Eaton’s Cuba Money Project published a list of Cuba-related projects that have received the most government funding since Trump took office. Humanitarian Christian Evangelism for Cuba occupies one of the first positions (USD 1,003,674). The group received approximately 2.3 million dollars from the U.S. government from 2009 to 2017.

The influence of the conservative American agenda is a key issue to be addressed, but it does not exclusively define the issue. And the former is also key.

Fake conscience?

The idea that these religious congregations “alienate” their parishioners, generate harmful emotional effects, or become rooted in groups with little schooling is short-sighted regarding what actually happens.

In the popular sectors, especially evangelisms have offered “the weapons to fight against social and personal suffering,” survival strategies, support networks, spiritual support, solutions to frustration, containment of precariousness, hope to get out of the crisis in social bond. These organizations go where many times the social commitments of States don’t go and where many social organizations that defend rights don’t go either, for different reasons,.

These faith communities offer rituals and build community. That matters to live and survive, even more in precariousness and crisis. On the other hand, their sexual and family policy is not necessarily the most undesirable option for concrete lives.

For many women, the re-traditionalization of families is no worse than couples leaving, beating, or using drugs. Integration into these faith communities can bring about a positive change, in which traditional roles can be a salvation in life: now the husband takes care of the house and she owes herself to him in better conditions. In return, they assume that “the truth” must be taken to every corner of society and of people. These are all legitimate needs. The strategies of those of us who defend rights must recognize them. The solutions to these needs are what we must dispute so that they become democratic, fair and inclusive. Faith communities that defend rights have a lot to contribute in this regard as well.

We must not confuse religion with fundamentalism or read the religious field as a bloc. Feminist Theology and, in general, rights-defending theology distances itself from the fundamentalist agenda and/or openly positions itself in favor of gender equality and LGTBIQ rights. In Cuba, this was visible during the process of dispute regarding egalitarian marriage. The Ebenezer Baptist Church, the Church of the Metropolitan Community of Cuba and the Baptist Student Worker Coordination of Cuba were among the voices that spoke in favor of the defense of rights.

In Cuba there are no updated public data on religious belongings. According to a 2019 Executive Summary of the United States Embassy in Cuba, the Catholic Church estimates that 60 to 70 percent of the population identifies itself as Catholic (although many times that refers to having been baptized, but doesn’t imply systematic religious practice), and membership in Protestant churches is estimated at 5 percent of the population (within which Pentecostals and Baptists are the largest denominations).2 There is no true data, but churches it is known that evangelical churches have increased very significantly and that many of them have an anti-rights agenda. The weight of militant religious conservatism as a whole was clear in the process of popular consultation of the Constitution. Although the content of egalitarian marriage is approved in the coming Family Code (for which we must fight tirelessly), beyond this there are agendas and actors.

The political question of why they exist, who they are, how do they expand and politicize and how far religious fundamentalisms have become rooted, needs to be answered by many actors. Reading what is disputed in Danay Suárez’s post requires going beyond the publication and entering pandemonium, that imaginary capital of the infernal world that those who exercise anti-rights see before them. To advance in this regard, we need to sharpen our eye towards the strategies they implement and assess the political impact they are achieving.

(To be continued)

Notes:

1 Thus, religious and secular anti-rights actors name a corpus from the feminist militancy and academia, which questions content considered dangerous for the traditional heteronormative family, traditional gender roles and traditional sexuality.

2 Other estimates speak of 10 percent of the population that defines itself as evangelical. Many evangelical churches are not officially registered. It’s very likely that the number of parishioners continues to grow and is greater than what is counted.