In “Elpidio Valdés se casa” (Elpidio Valdés gets married; Juan Padrón, Tulio Raggi and Mario Rivas, 1991) the mambí Colonel and Captain María Silvia need Prefect González to get married. The act is certified after a chain of adversities has been overcome and a series of legal requirements have been met, just before enemy fire on Tocororo Macho.

The depth of the historical research carried out by Juan Padrón (1947-2020) to conceive the series of Elpidio Valdés, an already mythical story of Cuban culture, is extraordinary. This episode recognizes a key to the culture of Cuban independence: the central role granted in it to law and order.

Militarism vs civic-mindedness?

Just six months after the start of the 1868 war, amid serious internal conflicts and with the East already facing the brutal Crescent of Valmaseda, the insurgent camp endowed itself in Guáimaro with its first Constitution (April 10, 1869).

This text covers a conflict that has been codified as “militarism vs civic-mindedness.” Carlos Manuel de Céspedes’ option in favor of centralized organizational forms for the management of war would represent militarism. The civic would be Ignacio Agramonte’s commitment to the limitation of individual power and in favor of parliamentary forms.

At the start of the conflict, Céspedes proclaimed himself “Captain General.” The exercise of his command aroused criticism from eastern leaders such as Francisco Vicente Aguilera, Francisco Maceo Osorio and Donato Mármol. The latter, in a quickly corrected act, tried to declare himself dictator and establish a separate post for Céspedes.

But also, while still Captain General, Céspedes was cheered patriotically during the events of the Villanueva Theater. [1] Then, when the Constitution of Guáimaro was approved, he took off that insignia of the military chief from his suit and put is at the service of the House.

However, for his critics, the accusation of “authoritarian” defined the entire path of the leader. For its part, the colonialist press exploited this accusation at length.

Civic-mindedness under review

The evidence confirms Agramonte’s civic-mindedness. José Luciano Franco has explained his “democratic republican creed” that defended “among other rights of man, that of resistance to oppression; administrative decentralization within unity of interests, ideas and feelings, in a State that must be founded on truth and justice.” [2]

In Guáimaro a “pure” parliamentarism was not formed, as the principles of “civic-mindedness” defended then were presented have been as “pure.” The Legislative was given powers typical of the Executive, such as the appointment and removal of the Chief of the Army.

Nor was the regulation of the powers of the president “pure,” which in addition to making him “prisoner” of the House, deprived him of the usual powers of an executive, such as granting pardons. For Céspedes, clemency was “the most beautiful of the attributes of power.” The Assembly denied that right, even for the House.

Neither was it very “parliamentary” that Camagüey, with a population of between 26 and 27% of that of the East, and close to 5% of the entire Cuban population―as Ramiro Guerra has pointed out―had the same representation of delegates as the East in the Constituent Assembly of Guáimaro.

The result was an institutional regime that made Máximo Gómez “almost always” not even know where the government was. Still less could he take orders from it.

Militarism under review

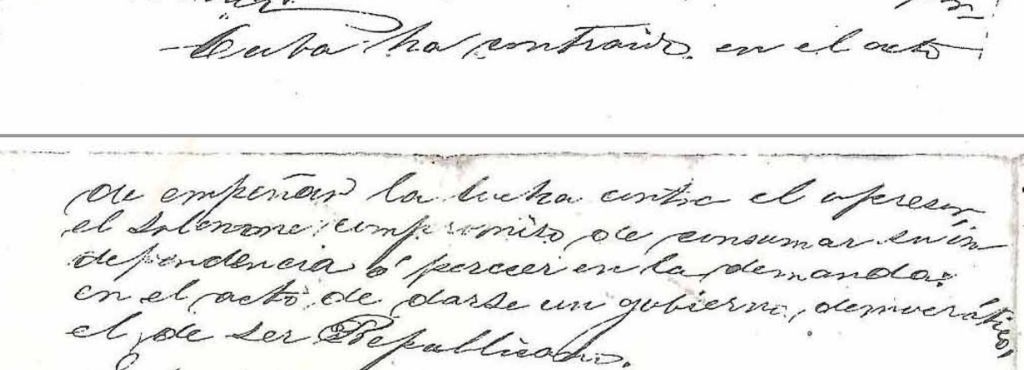

When he was elected the first President of the Republic of Cuba (in arms), Céspedes proclaimed: “Cuba has contracted, in the act of pledging the fight against the oppressor, the solemn commitment to consummate its independence or perish in the demand: in the act of having a democratic government, that of being republican.” [3]

The Eastern leader was also favorable to the parliamentary regime. His was the suggestion that the secretaries of the office be submitted to the approval of the House.

Since 1868 Céspedes himself assured that with the uprising we can already “enjoy one of the greatest assets that free peoples enjoy; that of freedom of the press.” He considered that right as the “shield of the defenseless peoples.” [4]

Such attention to rights was not just declarative. The mambí press collects many different positions. In the name of that freedom, “Anita” Betancourt and Agramonte presented their famous plea for women’s rights before the assembly in Guáimaro. [5]

Céspedes announced that “we want freedom in all spheres; we conceive political freedom as the crowning of the building, thus supporting civil freedom, at its foundation.…” Those principles, said the man of La Demajagua, “are, in our opinion, the foundation of public freedom.” [6]

The revolutionary also defended in practice that set of rights. He himself set fire to his property―a singular event in the history of any country, he freed those who were enslaved―certainly an act of ownership, Rebecca Scott has pointed out, but that meant an earthquake for the slave economy, and he was consciously ruined.

By 1871 the presence of the ex-slaves in the war had already generated the definitive anti-slavery character of that conflict, an incomprehensible process without Céspedes’ impulse.

Céspedes argued with Salvador Cisneros Betancourt about the concrete practice of the right of free movement.

Cisneros demanded not to leave the territory in arms at all. Céspedes said that the right of free movement was “inalienable and imprescriptible,” that it could only be curtailed “in the name of extraordinary demands and higher transcendence.” He concluded that denying it in a general way would be equivalent to the exercise of a “true despotism.” [7]

In one of his reports of accountability to the House, Céspedes recognized the importance of the functioning of that body and criticized the exaggerated military decentralization, which could give rise to “bastard ambitions that may arise.” [8]

In addition, he demanded the attention of the House about the War Councils and the conditions to suspend the habeas corpus. His intention was to avoid the creation of an “almost dictatorial omnipotence of military power,” which he considered to be inconsistent with the “absolutely democratic tendencies of our fundamental code.” [9]

None of this seems like an anti-rights language or practice.

A true label, but disregarded

A historiographical line has advanced beyond the dichotomy of “militarism vs civic-mindedness.” According to Tirso Clemente, “Guáimaro was not the scene of heated debates between civilians and militarists, democrats and exponents of despotism. There was no discussion of an ideal system of government; a formula accepted by the parties was taken there.” [10]

Before, Ramiro Guerra and Sánchez assured: “In Guáimaro young people made politics, ‘realistic,’ very adapted to the current objectives of the political parties under similar conditions: to achieve positions, obtain advantages, make criteria prevail, win followers, secure majority and assume the greatest possible amount of power.” [11]

The conflicts of regional power―the idea of a “hometown” was very relevant at the time―and around the control of the process of the revolution are crucial to understand Guáimaro.

Among current scholars, Rafael Acosta de Arriba has taken a decisive step to think beyond this dichotomy. He has argued that Céspedes had “a clear republican and democratic projection.” The same is said of Agramonte.

It is a system of ideas that included, also in Céspedes, “universal suffrage, government decided by the people, sovereignty and national integration, all of which have been practically hidden from his political thought.” [12]

The label “civic-mindedness vs militarism” still weighs, which exposes the disunity of the patriotic forces that led to the falling through of the war of 1868.

The explanation is true, but it loses sight of contents that those who were “civic-minded” and “militarists” shared and that produced the miracle of Guáimaro and, above all, the extraordinary fact of sustaining the war for ten long years in the midst of unspeakable hardships.

One of those floors, common in Céspedes and Agramonte, is the idea of the constitutional homeland, which involved devotion to the Republic and respect for its laws.

The debate on the flag exemplifies this. The defense of the Narciso López banner―the “national” as used and recognized to date in various regions of Cuba―over Céspedes’ ensign―the “regional” specifically of the East―ended with the first one being accepted by all, as the flag “of the Republic.”

At the time, when the nation was just at the beginning of its construction process, harangues such as “Long live Oriente” or references to the “typical sons of Camagüey” were common. It is necessary to be aware how the cry of ¡Viva Cuba Libre! was thus profoundly unifying. [13] As was the approval of a Constitution―through negotiation―for all regional trends.

The Prefect González, the Law and Cuban democracy

The Administrative Organization Law (August 7, 1869) created a territorial political structure that included prefectures and sub-prefectures. The character of Prefect González, from the Elpidio Valdés episode, is based on that.

As in any context, there were complaints about some prefects. One from Maraguán (Camagüey), was singled out for returning freemen to their former masters. But also “some freemen saw revolutionary prefects as their potential defenders, so that when they were mistreated they turned to them for justice.” [14]

The House of Representatives approved—an all-out global event—the law on civil marriage (1869) to which Elpidio and María Silvia were “forced.” It was also agreed on the linked divorce—another event—among the causes of which was “mutual dissent.” [15]

Céspedes vetoed the civil marriage law with conservative criteria and secularism was not his bet, but that of Camagüey. Now then, Prefect González fulfilled―in fiction—the legitimate law with the same zeal that Céspedes did in reality.

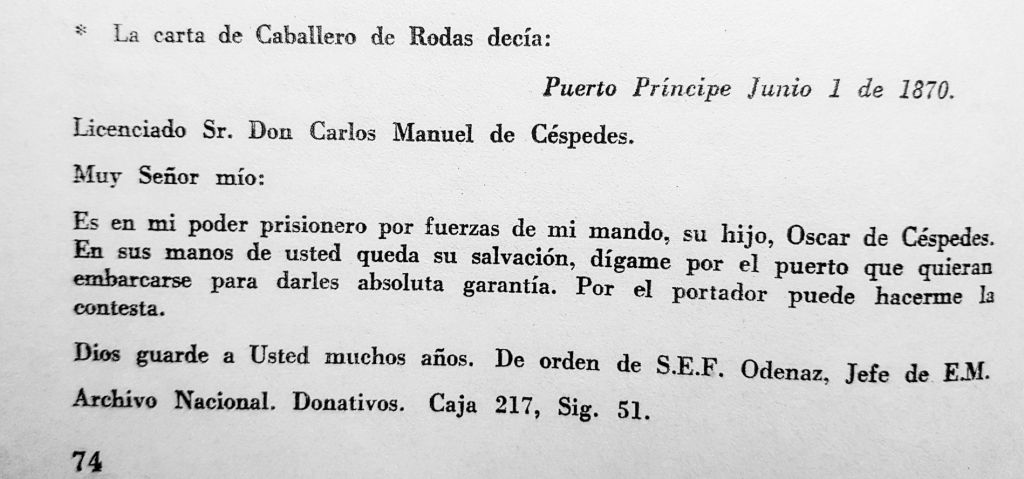

The man from Demajagua is considered the “father of the nation” for accepting the sacrifice of his son Oscar before negotiating a deal for his salvation. [16] He must also be considered a friend of that collective—and conflicting—creation that is democracy in Cuba.

Notes:

[1] Album histórico fotográfico de la Guerra de Cuba desde su principio hasta el reinado de Amadeo I. (1872), La Antilla printer’s, p. 21

[2] José Luciano Franco (2009) “La Revolución de Yara y la constituyente de Guáimaro”, En Guáimaro. Alborada en la historia constitucional cubana… p. 107

[3] Antonio Pirala (Historia de la guerra de Cuba, editor Felipe González Rojas, Madrid, volume I, 1895) transcribes this last phrase as “that of being a republic” (p. 476). I copy it as I think I read it in the original manuscript, according to a document available in the National Library of Spain.

[4] El cubano libre. Year 1. No. 3, October 25, 1868.

[5] In José Luciano Franco (2009), “La Revolución de Yara y la constituyente de Guáimaro”… p.112

[6] El cubano libre. Year 1. No. 3, October 25, 1868

[7] “De Carlos Manuel de Céspedes a Salvador Cisneros Betancourt” (1919) In Guáimaro. Reseña histórica de la primera Asamblea Constituyente y primera Cámara de Representantes de Cuba, by Néstor Carbonell and Emeterio S. Santovenia, Havana: Seoane y Fernández printer’s, pp. 145-149

[8] “Del Presidente de la República a la Cámara de Representantes” (1919) In Guáimaro. Reseña histórica de la primera Asamblea Constituyente… pp. 191-197

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tirso Clemente Díaz (2009). “La labor constituyentista de Ignacio Agramonte” In Agramonte”, En Guáimaro. Alborada en la historia constitucional cubana (Comp.s Andry Matilla Correa and Carlos Manuel Villabella Armengol), Camagüey: Universidad de Camagüey publishers, p. 161

[11] Historia de la nación cubana. (1952) (Ramiro Guerra and others), tome V, Havana: Historia de la Nación Cubana, S.A. publishers, p. 82

[12] Rafael Acosta de Arriba, (2019) “El angustioso y difícil camino hacia Guáimaro en 1869”, in Cuando la luz del mundo crece, Camagüey: El Lugareño publishers.

[13] A Spanish eyewitness would say: “The uprising of the Eastern Department…was frank and of course open: the flag of independence was raised to the voice of Viva Cuba libre! The insurgents of the Central Department also said Viva Cuba libre!” In Album histórico fotográfico de la Guerra de… p. 43

[14] Rebecca Scott (2001) La emancipación de los esclavos en Cuba, Havana: Caminos publishers, p. 81

[15] Julio Fernández Bulté (2005). Historia del Estado y el Derecho en Cuba, Havana, Félix Varela publishers, p. 124

[16] “Oscar is not my only son, all Cubans who die for our nation’s freedoms are.” Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. Escritos. (1982), (Comp. Fernando Portuondo and Hortensia Pichardo), Volume II, Havana: Ciencias Sociales publishers, p. 74