Wilhelm Steinitz was no longer world champion when he played his best game of chess. He lost the crown in the spring of 1894 against young German Emanuel Lasker, but a year later, while everyone thought his talent was gone for good, he was reborn as Phoenix on the difficult 64 square board.

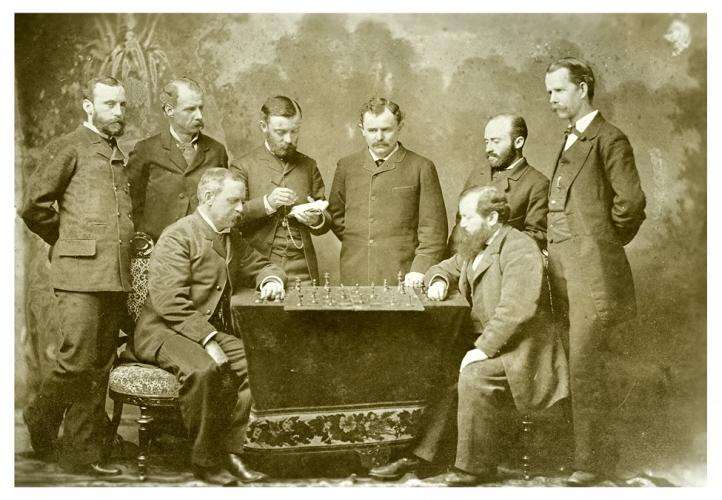

He played the masterpiece in the mythical Hastings tournament, perhaps the most famous in history, bringing together the cream of the era: the very same Lasker, Pillsbury, Chigorin, Tarrasch … Then, already 59, the former monarch was only fifth in the standings, but made his mark with a dazzling game that deserved the Beauty Award in that event.

His victim was a high-priced player, Curt Von Bardeleben, who reached the tenth round occupying the third position, just half a unit away from the vanguard. And the weapon used was the depth of calculation, exploded to almost inhuman limits by a cold brain, that that afternoon, meant the humiliation of the opponent.

Oddly, because crushing his opponent hadn’t been for some time high on the philosophy of Steinitz. Years before, fueled by a pothole in the sport, he had moved away from the romantic connection of his contemporaries Paul Morphy and Adolf Anderssen, and started to battle for a personal solution to chess. Thus, from the relentless attack against the kingside, the Austrian had led to the founding of a less exciting, but more scientific, school.

The positional style, his great contribution, led Steinitz to raze wherever he played, to design novel variants (and still valid) for the French Defense and the Spanish Opening, and defeat each of the great masters of the late nineteenth century, including Polish Johannes Zukertort in the first of the matches for the world championship, held in 1886.

Three times he successfully defended the throne. He did so against Russian Chigorin in two clashes with Havana as the venue where Capablanca was just a kid, and against the Anglo-Hungarian Isidor Gunsberg, in New York. But then health did not accompany him versus the formidable Lasker, gave up the scepter and began the decline of his star.

However, nothing depleted his inheritance. Countless critics of his character were born from that irascible character of his and from the conservative way he understood chess, but Steinitz, with unflagging faith in him, overcame everything. So, he let the pillars supporting modern school, so dependent on the strategies in the middle game, and taught forever that small advantages accumulate to give the win after building a compact position on the board.

On August 12, 1900, Wilhelm Steinitz died raving mad and miserable. Sad end for a guy so lucid that, just five years before, had written the following page:

Blancas: W. Steinitz – Negras: C. Von Bardeleben

1.e4 e5 2.Cf3 Cc6 3.Ac4 Ac5 4.c3 Cf6 5.d4

They agreed on the Italian Opening or Gioco Piano

5…exd4 6.cxd4 Ab4+ 7.Cc3

Typical. Though they could have played as well 7.Ad2 Axd2+ 8.Cbxd2 d5 9.exd5 Cxd5 10.Db3 Cce7 o 10.0-0 0-0 with relative parity.

7…d5!?

Taking the pawn (7… Cxe4!?) has the risk that after 8…Axc3 9. d5!, you enter the feared territories of the Moeller attack.

8.exd5 Cxd5 9.0-0! Ae6!

If 9…Cxc3, then 10.bxc3 Axc3?! 11.Axf7+ Rxf7 12.Db3+ e6 13.Dxc3 with initiative on the exposed king.

10.Ag5!

The ambitious White pieces’s plan starts loomimg

10…Ae7

Now, with a series of exchanges, Steinitz keeps the black King in the center of the chessboard

11.Axd5! Axd5 12.Cxd5 Dxd5

If he took bishop on g5, blacks will lose pawn on 12…Ag5 13.Cxc7+ Dxc7 14.Cxg5.

13.Axe7 Cxe7 14.Te1

That’s the point where Steinitz wanted to go. Nailing the horse, the white pieces prevent castling and retain the opponent’s king without safety improvements.

14…f6 15.De2 Dd7

He protects his knight and at the same time square b5.

16.Tac1!? c6?

The needed move was 16…Rf7, in order to connect teh rooks and restore balance.

17.d5!!

A nice sacrifice aimed at gaining the d4 square. If the black declines to accept the pawn 18.dxc6 derived in an attack through the open central columns.

17…cxd5 18.Cd4! Rf7

A must. Si 18…Tc8?? 19.Txc8+ Dxc8 20.Dxe7 and mate.

19.Ce6!

According to Steinitz, this knight was “a bone stuck in the throat of old Bardeleben”.

19…Thc8?? 20.Dg4!

This move generates multiple threats, as wiining the queen and mate in two after Dxg7+.

20…g6

There was no other defense left. Si 20…Txc1?? 21.Dxg7+ Re8 22.Df8#, y si 20…Cg6 21. Cg5+, with obvious material superiority

21.Cg5+

White proceeds to a tremendous combination that is supported by the unfortunate location of the rival King.

21…Re8 22.Txe7+!!

Experts agree this movement qualifies as one of the brightest ever played. Note that the target is now on the brink of Txc1 mate. But there is nothing to do for Bardeleben. If 22…Dxe7, 23.Txc8+! defines right away. And if 22…Rxe7, then 23.Te1+ Rd6 24.Db4+ Rc7 (24…Tc5 25.Te6+) 25.Ce6+ Rb8 26.Df4+ Tc7 27.Cxc7 and the story is over.

22…Rf8!

The black pieces appeal to their last resort. Steinitz remains under threat of mate at one, so there is no use for him to take the Queen. At the same time, all the pieces are being harassed. But if there is magic…

23.Tf7+! Rg8

23…Dxf7 would be suicide due to 24.Txc8+!

24.Tg7+!

The rook mocks the adversary with impunity

24…Rh8

Obvioulsy, 24…Rxg7?? hands over the queen and the game. And if 24…Dxg7? 25.Txc8+ Txc8 26.Dxc8+ Df8 27.De6+ Rh8 28.Cf7+ Rg7 29.Cd6, with clear advantage. Finally, 24…Rf8 gets a mortal shot with 25. Cxh7+.

25.Txh7+!!

At this point, Bardeleben forgot all the rules and left the room without shaking hands with the opponent. They say that he looked at Steinitz, and without a word he rose from his chair, left the room and never returned.

So, to be officially declared the winner, Steinitz had to wait for that time was consumed in the clock of his adversary: no less than 50 minutes. Then he showed viewers how triumph came in all possible variants. Namely:

25…Rg8 26.Tg7+!

The opening of the column allows the decisive intervention of the queen.

26…Rh8

Mandatory, because if 26…Rf8? 27.Ch7+ finishes all.

27.Dh4+! Rxg7 28.Dh7+ Rf8 29.Dh8+ Re7 30.Dg7+ Re8 31.Dg8+ Re7 32.Df7+ Rd8 (32…Rd6? 33.Dxf6+ De6 34.Dxe6#) 33.Df8+ De8 34.Cf7+ Rd7 35.Dd6#

This done, a round of applause crowned the Maestro’s day. Jacques Hannak, his biographer, wrote later that “this was the ultimate expression of a dream in which all the greatness and happiness imagined in his youth, gathered on a warm August 17, 1895, the day he won brightest match of his life. ”

The quote: “I can play against God; give him the white pieces and a pawn.” Steinitz.