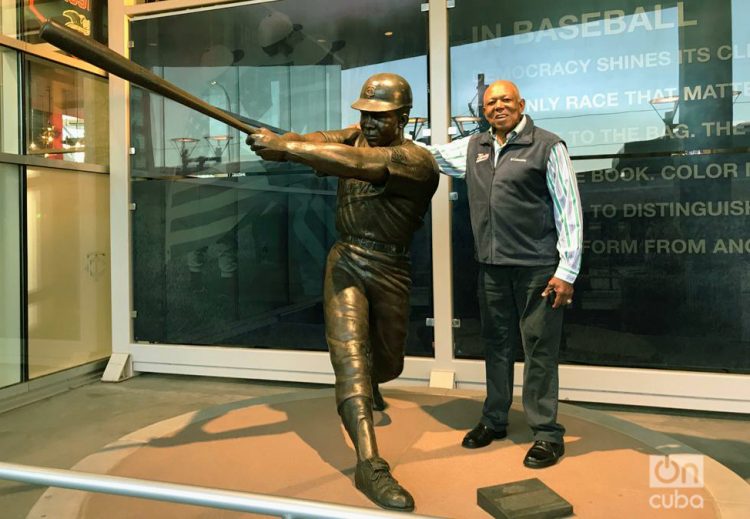

Since April 2011, all the fans who have entered Target Field through gate #6, in the left field of Minnesota’s baseball temple, have come across the figure of Tony Oliva (Corralito, 1938), sculpted in bronze, immortalized as one of the legends in the history of the Twins.

The statue of the native of Pinar del Río bats a compact swing heading for eternity. It could not be otherwise, because much of his legacy was cemented by his exquisite technique at the plate, from where he intimidated, standing left, every pitcher who crossed his path as of 1964.

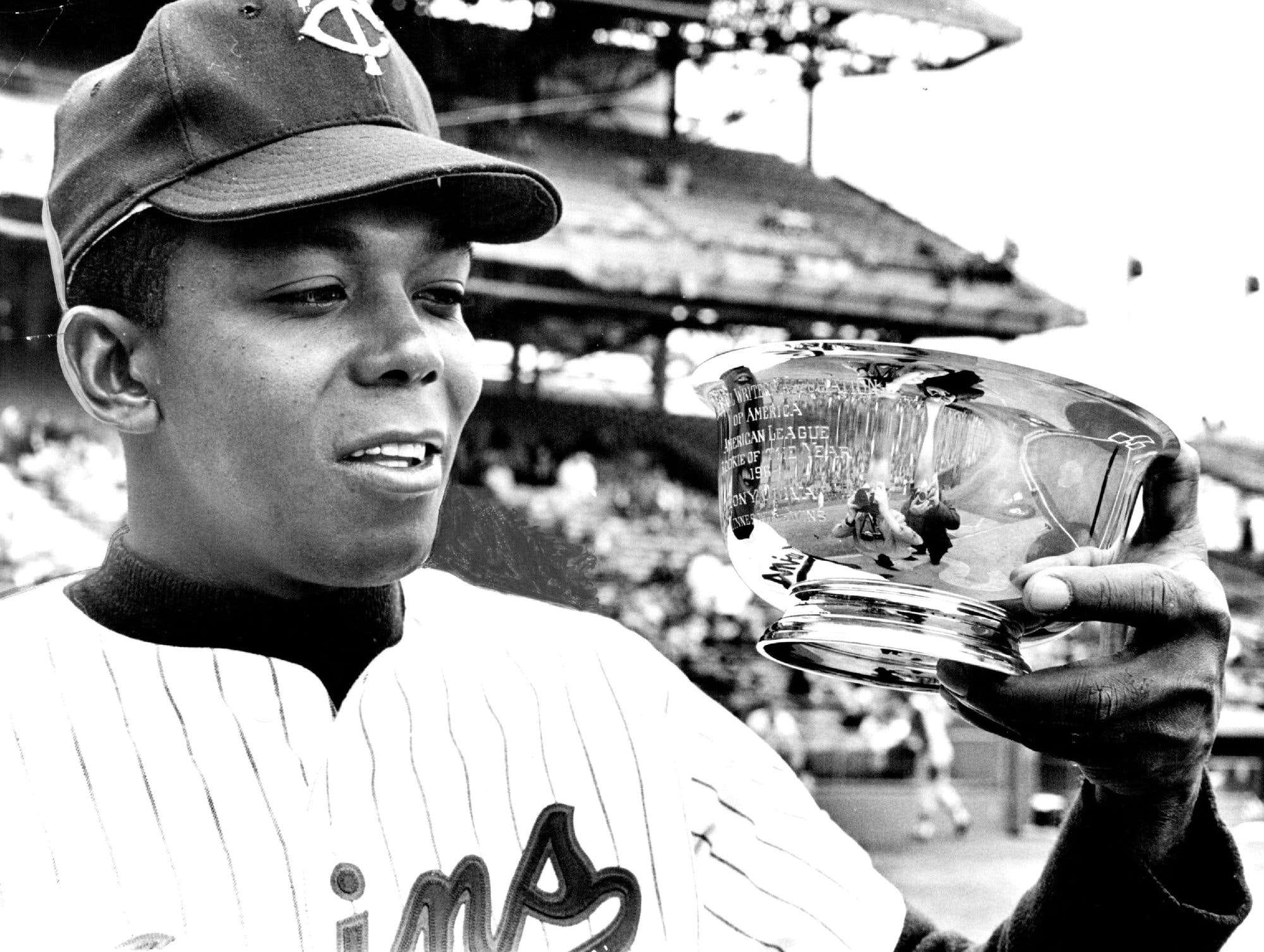

Precisely that year he entered the Major League diamonds like a hurricane and won “Rookie of the Year.” Then came a string of successes and awards, including eight All-Star calls, three batting titles and five hitting leads — something that, incidentally, only three true monsters such as Stan Musial, Pete Rose and Tony Gwynn have achieved.

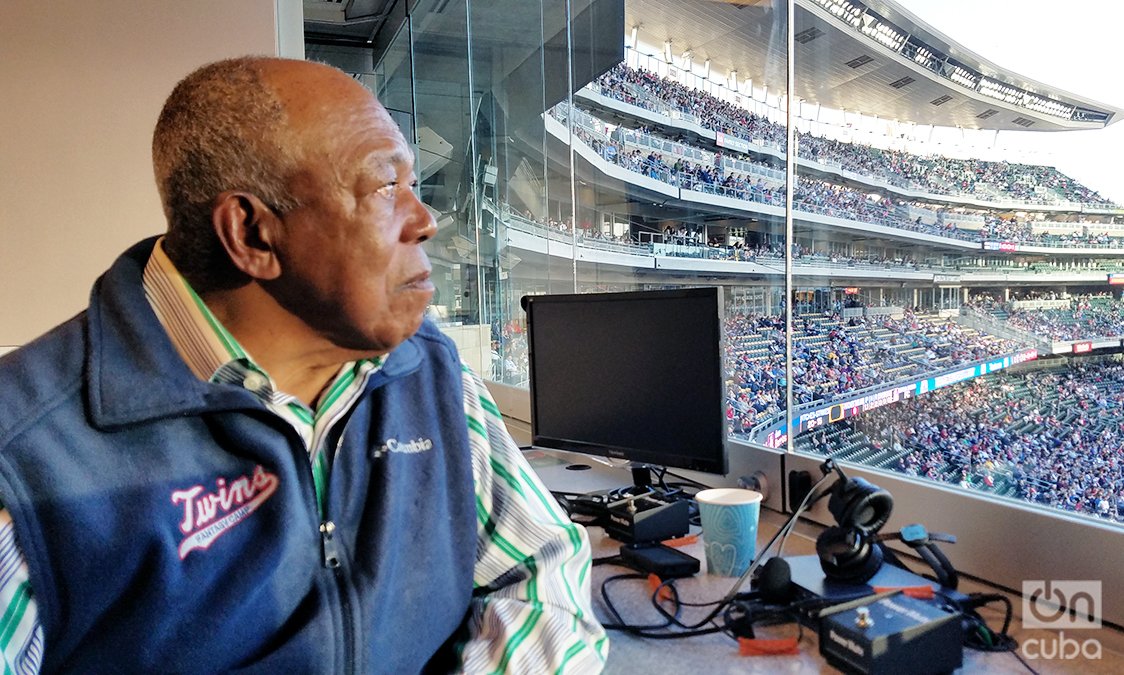

For all that, Oliva is an adopted son of Minnesota. There, as is to be expected, he pervades like a king of the diamond, although he is also a reference for the community, which does not ignore his social work, his approach and support for the disabled, the poor, the elderly and Latinos.

If possible, the figure of Tony Oliva is, since last December 5, even more revered in Minnesota and in all the corners where he left his mark, after being inducted by the Veterans Committee as a new member of the Cooperstown Hall of Fame.

“It was a very big surprise. I’ve been waiting for my turn for a long time, but those who vote had taken their time. I feel very happy, very proud, very content, for me and for all the people who support me,” Oliva said exclusively to OnCuba.

At 83, the legendary player from Pinar del Río claims to have a tighter schedule than ever. “My phone has never been so busy,” he jokes in the middle of a relaxed chat, in which his love for “Cubita,” as he calls the land where he was born, comes up again and again.

You had been on the Veterans Committee ballots before and had come close to being elected. Did you see the possibility of being elected now very far?

I think this year I had more chances than ever. I had been very close the previous time in 2015, when I was only missing one vote; that was amazing. Now I still had faith, but if I did not enter, forget it, because my numbers are good enough to continue on the ballot, but if you miss a year for one vote and the next time you are left with less support, they will hardly take you into account for the future.

The best thing about this waiting process has been the support of the fans, the club, the family, everyone was very positive, thinking that I could reach the Hall of Fame this year.

What were the feelings when you got the news?

Imagine, I hadn’t been waiting one or two years for this, I had been yearning for a moment like this for almost 45 years and it didn’t happen. Now when the phone rang, it was the president of Cooperstown, and I felt great satisfaction, for me, for my family, for the people who were inside and outside my house waiting for the news, good or bad. That has been the main thing, to feel how so many people have been waiting and supporting.

After the election was confirmed, I’ve experienced a kind of big revolution. Wherever I go people congratulate me, the phone doesn’t stop with calls from Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Venezuela. It’s been madness.

How did people who were close to you and family in Pinar del Río receive the news?

I think they found out before I did, because my brother called me right away. Everyone was very happy. The expressions of affection and recognition from Cuba are of great value to me, because many people who congratulate me from there didn’t even see me play and some didn’t know who Tony Oliva was until a while ago.

You have been chosen alongside Orestes Miñoso, who ended his Major League career just as yours began. How valuable is the figure and the legacy of Miñoso for Cuban and Latino players?

Minoso touched many lives because he played in a very strong era, of great demand. I didn’t see him play at that time, but I remember listening to the games on the radio and even having a song dedicated to him: “When Miñoso really hits, the ball dances the cha-cha.” I don’t forget that chorus. He was an idol for all of us.

Later I had the opportunity to meet him here in the United States and to share with him several times. I always thought that he would enter the Hall of Fame earlier because of his quality as a player and because he was and is an inspiration. He broke the racial barrier for Latino players and in what a way, as a great player. I say that, among all the stars of that time, Miñoso deserves double recognition, because he endured the humiliations to which blacks were subjected and shone on the field.

Although times had already changed a bit, when you arrived in the United States, many blacks were still exposed to segregation. How did you experience that phenomenon when you were already a public figure?

It didn’t affect me that much because I knew what I was getting into, I knew the rules and how things worked in the United States. There was also a bit of racism in Cubita in those years, places where blacks couldn’t enter, for example, so in that sense I arrived prepared. In any case, the impact feels the same, because sometimes one didn’t have where to eat and you had to live secluded in black neighborhoods.

To what extent did these conditions affect your promotion to the Major Leagues?

Well, from the outset I felt the consequences of segregation as soon as I arrived in the United States; I was left out of the team in spring training because in the southern states the clubs had a limited capacity to include black players. I got there late due to visa problems, so I had to watch everything from the stands.

Luckily, Rigoberto Mendoza, a Cuban who was in the organization before he moved to Minnesota, saved me. I remember that he spoke to the general manager and insisted that they give me a chance. Joe Cambria, a scout who had recruited hundreds of players from the island since the 1930s, found me a place in the Rookie League. He also made a point.

From there onward I was happy, because I surpassed that level very quickly. I hit over .400, with over 100 hits in sixty-odd games. In Class A and AAA things still went well for me, hitting home runs, with averages above .300 and more than 150 RBIs. That opened the doors to the Major Leagues for me in a relatively short period of time.

But returning to your question, all this happened in a somewhat complex scenario due to the issue of racism, the language barrier, which I did not know very well, and because I was far from the family, with practically no options to return to Cuba, because already there was a lot of tension between the two countries. Fortunately, I had the support of Zoilo Versalles, Camilo Pascual, José Valdivieso, Julio Bécquer and other Cubans who were already in the Major Leagues. They were like my babysitters, they helped me with the language, to order food, they accompanied me and guided me to get home or any other place. They became my brothers and we are still very close today.

Speaking of baseball, what was the hardest thing in those early years in the United States?

The defense, without a doubt. In my first season in the Rookie League I made like 14 mistakes and my fielding rate was a disaster. Imagine, I had never played ball in an organized way. I was a farmer, my life was going to school and then working on the farm harvesting cassava, taro, tobacco and everything that appeared. In Pinar del Río, Roberto Fernández Tápanes, a player in the Professional League and in the Minors, had seen me and realized that I did everything well except fielding.

And indeed, when I arrived in the United States my problem was to field the ball, I couldn’t catch the rollings, the flys and it was difficult for me to play at night, something I had never done. Then I began to look at what Al Kaline, Roberto Clemente or Willie Mays did, they became my references. I worked hard, always attentive to the guidance of the coaches, because I wanted to be better, a well-rounded player. In the end that worked for me and I even won a “Golden Glove.”

You had defensive problems, but the talent with the bat came from the cradle….

My batting has always been good. From Cuba I forged that trust. There I played very little baseball, but I practiced at bat with my brothers, who from time to time threw me caps, cobs or anything else so that I could improve my swing and could play on Sundays.

In the United States, when I arrived and they left me out of the team, I remember sitting in the stands, watching the games, watching all the players and knowing that I could hit any opponent. I was very confident in my skills as a batter. Then I showed it on the field in a very tough pitching season, facing and connected against rivals such as Sandy Koufax, Jim Palmer, Mel Stottlemyre, Mike Cuellar, Rich Gossage, Luis Tiant or Catfish Hunter.

Have you ever thought how far Tony Oliva could have gone had it not been for the knee injuries and operations?

Look, I got injured in Oakland trying to field a Joe Rudi balloon. I looked to catch the shoelace ball and, when I fell, I put my knee in a little hole where there was a water tube. There my menisci broke and the rest is history. I could never go back to the outfield. I played single-legged for the rest of my days, as a designated hitter, and so I had three seasons with more than 120 hits and always with more than 100 RBIs.

So, imagine, without injury my numbers would have been much better, because I came out of the game in one of the most stellar moments of my career, but it is not something that torments me. I am very happy with what I achieved before and after the operations.

Did you get over not winning a World Series?

It’s necessary to have tremendous luck to win a World Series, because your opponents are also champions. We in Minnesota lacked the last push. In 1965 we got to the last game against the Dodgers and we couldn’t. Already in 1969 and 1970 we won our division, but we lost to the Orioles for the American League title. Either way, I was able to get over that, as you say, in 1987 and 1991, when I won the World Series with Minnesota as the team’s instructor hitter.

Any reference to your career inevitably leads to Minnesota. How much does the city represent to you?

Minnesota is my second homeland. “Cubita” is my first homeland, where I was born, where my roots are, where I took my first steps, and Minnesota has been my second home. Here I made my family, I’ve lived here for more than 60 years. In the organization they have treated me very well, both when I was a player and after I retired. I can’t complain, because the community has been great to me too. It is a beautiful city, very quiet, with very friendly people….

Your parents and your siblings never saw you play in the Major Leagues. How did you experience those successful times on the field away from the family?

It was very hard. Many people don’t know what one went through, what it means to be alone. Even if you have all the success in the world, the family is very much needed, especially when you finish a game and you have no one to share with. That feeling of triumph sometimes turns into sadness, because you want to be with your parents, enjoy it with those close to you.

But fate is like that. I know my family was supporting me at all times, from a distance, and we never broke ties. And I know that they lived with great pride all my achievements and also those of my brother Juan Carlos, one of the great pitchers in the history of Pinar del Río and Cuba.

Who would come out losing in a duel between you and your brother (Juan Carlos)?

It’s a good competition because he’s going to try to get me out, I’m sure, really sure, and I’m going to try to bat him out. If he takes me out, he will laugh at me, but we will always win, because victory remains in the family.

Would you have liked to play in Cuba?

Yes, sure. I would like to have played for Cienfuegos, in the Professional League. Pedro Ramos, also from Pinar del Río, played there, and he was a reference for me. I am convinced that it would have been a great experience to enjoy the Cuban fans, to play in front of those who never saw me and don’t know what kind of player I was.

Being inducted into Cooperstown is a recognition of your career, but in the hearts of many fans you were already an immortal. What message do you have for these ever-faithful fans from Minnesota, from Pinar del Río, from Cuba?

My message is one of gratitude, for my fans, for my family, for all the people who carry me in their hearts. I am very pleased that this award has been celebrated equally in Minnesota and in Pinar del Río, two points that are more than two thousand kilometers apart. It is a sign that, regardless of distance, we can be united by baseball. Getting to Cooperstown is not an award just for me, it is for you as well.