If you’re not used to it, you can’t drink it down in one gulp. One sip and then another; your glass is still almost full. “It’s a velvety rum with a lush bouquet, very enduring….” says rum master Tranquilino Palencia, speaking as though he were reciting a poem. He is referring to Santiago 500, the “newest” of the aged rums produced in Cuba, named in honor of the legendary eastern Cuban city’s 500th anniversary.

It is the city where light rum was first created, in 1862, definitively surpassing the coarse pirates’ beverage known as rumbullion or tafia. Rum’s origins, intertwined with the sugar industry and slavery of the Spanish colonial period, root it firmly in the island’s identity and history.

And of course, that ancestry is a motive for pride on the part of santiagueros. Architect Omar López, director of the Santiago de Cuba Conservator’s Office, explains the formula as if it were a riddle. “They say that Cuban rum is the best in the world. I think that if Santiago rum is the best in Cuba, then Santiago rum is the best on the planet.”

This is also the city of boleros, son, trova…and musical tradition has become interwoven with the culture of drinking, all of it wrapped up in a halo of romance, playfulness and heartbreak, going back to the times of Pepe Sánchez, Ñico Saquito and Sindo Garay.

In Cuba’s “most Caribbean city”—perhaps like nowhere else—rum is synonymous with fiesta, carnival, and conga lines sweeping down Trocha street. It is for good reason that rum was described as the joyful offspring of sugar cane” by Cuban journalist and writer Fernando González Campoamor.

Today, Cuba has seven rum masters nationwide, and three of them are from Santiago. They ensure that the right balance is maintained between a century and a half of legacy and modern technology and good practices. Their future successors are six rum master candidates, which for the first time include women—five of them.

Sensory evaluation and knowledge passed on from one generation to the next provides a certain mystique to the production process, especially in the case of dark or extra-aged rums. Some oak barrels can be up to 90 years old, and it is precisely the oldest ones that are chosen for the final stages of aging.

In the vaults, the atmosphere feels dense and the smell seems to stick to your body. “The rums that have passed through several types of barrels generate an extraordinary taste,” says Palencia, who does not hide his passion for his trade.

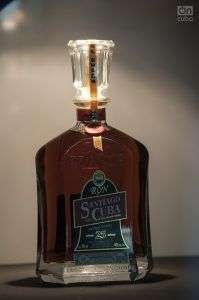

Santiago 500 is categorized as “brightly dark amber.” Like other rums from the same family, it is characterized by a long “duration in dry cup,” (permanencia en copa seca) according to rum jargon. The jewel-shaped bottle seen in the photo will cost around $5,000, Limited Edition.

When having an intimate conversation or family dinner, one will have to think twice before pouring a few drops on the floor, “for the saints.” A gesture like that confirms the long tradition of drinking in this nation´s customs, whether or not for religious reasons.

Contrary to what some might think, Top Rum Master Juan Carlos González says there is no “magic recipe.” “Obviously, there are things that we don’t announce from the rooftops; nobody does that. But even if it were told, it can’t be repeated anywhere else. I think the main secret of Cuban rum is our country: the soil, the climate, our history, and our people.”

Every variety is distinguished by the particular flavor of the region from which it comes. “Rums are different according to region: in the west, they have been drier rums; central Cuba specializes in semi-dry rums; and they always say that Santiago rums are the sweetest in the country,” says Isabel Cristina Rivero, the first woman rum master candidate.

“It is a single cultural expression, but with flavors and aromas that are consciously differentiated, as seen, perhaps, in our culture of mixed parentage,” says Top Rum Master José Pablo Navarro, leader of this movement.

In 1947, historians from all over the country gathered here, led by Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring, and they decided to declare Santiago “the city of history.” Many also refer to it as the “scenic outlook city” because of its undulating, hilly streets. From the highest streets, you can see the ocean and the Sierra Maestra mountains, and all of their beauty.

The Don Pancho aging vault is in the middle of what’s known as the “rum zone.” Some people say that Santiago’s Rum Museum, which is about to turn 19 years old, is prettier than Havana’s. “This is the original,” they say.

The history that the rum masters watch over here is one they know by heart. They have lived it, they are part of it. In their vaults, they receive the work of others, and at the same time, they will leave long days of work to the coming “heirs.” As Navarro says, they must be capable of predicting, of dreaming about what they will make in years to come. “A Cuban rum master is a dreamer who knows how to create.”