U.S. university professor Sara Cooper is the founder of a veritable publisher’s dream: Cubanabooks. The publishing house has already begun to secure prestige in both Cuba and the United States thanks to the tenacity of a woman who defends literature written by women and Queer Studies.

She is currently working at the California State University, devoting much of her time to publish the work of Cuban women living in the United States.

At a time when curiosity about Cuba may well extend to its literature, Sara Cooper has a feeling that her project may become one more way for the countries – which opened their respective embassies on July 20 – to begin a difficult normalization process to involve the sphere of culture – to get to know each other better.

We approached Cooper to learn more about her and her expectations for her initiative, which has neatly become a reality and one more bridge between the United States and Cuba – an initiative focused through the lens of women, the always neglected gender that struggles to secure the place it deserves on both shores of the Strait of Florida.

How, when, why and with what aims was Cubanabooks born?

Cubanabooks was established in 2010 with the publication of our first book, an anthology of short stories by Mirta Yáñez (Havana Is a Really Big City). Then, in 2011, we transitioned into the non-profit sector.

For many years, I had been interested in Cuban literature, and women’s literature in particular. In 1998 I met Mirta Yáñez. We developed a strong friendship and collegial relationship, on the basis of which I began to translate some of Mirta’s stories into English for eventual publication in the United States.

Given the multiplicity of obstacles that stood in the way of achieving that end, over the span of a few years, I almost gave up. Publishing houses (big and small) didn’t want to take the risk with an author who was unknown in the United States and didn’t write detective or erotic stories. They were also afraid about the legal and financial implications stemming from the embargo.

After many long conversations with Mirta, we decided we were willing to “change the world,” and so we took on the work of creating a press dedicated to publishing first class literary texts by Cuban women. And that’s when we came up with the name Cubanabooks.

Another objective of ours is to publish in bilingual editions. . I didn’t want just my English-speaking friends and relatives to get to know the treasure of Cuban literature, I also wanted to have a source of Cuban literature for the Spanish classes I teach at university. Aside from the first, all of the books we have put out have both the Spanish and the English, which makes them available to a broader audience.

More and more, we consider that our most important aim is to build bridges between the two countries, at a historical moment many did not imagine they’d live to see. One integral part of this is to make possible a consistent exchange between women from Cuba and the U.S., because we have so much we can learn from each other.

What books has Cubanabooks published to date and which are currently being edited?

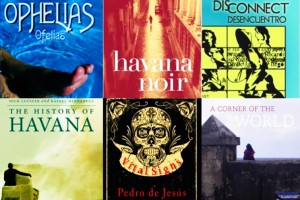

In addition to the books I’ve mentioned, our publishing house has published other volumes, for a total of eight books, namely: two novels (The Bleeding Wound/Sangra por la herida, by Mirta Yáñez/trans. Sara E. Cooper, and The Memory of Silence/Memoria del silencio, by Uva de Aragón/trans. Jeffrey C. Barnett), three short story anthologies (Disconnect/Desencuentro, by Nancy Alonso/trans. Anne Fountain, Ophelias/Ofelias, de Aida Bahr/trans. Dick Cluster, An Address in Havana/Una dirección en La Habana, by María Elena Llana/trans. Barbara Riess) and two volumes of poetry (Homing Instincts/Querencias, by Nancy Morejón/trans. Pam Carmell, and Always Rebellious/Cimarroneando, by Georgina Herrera/trans. Juanamaría Cordones-Cook).

We have four stages of review and editing, from the initial consideration of a text in the original Spanish, with several of the editors opining, to the detailed final editing of the bilingual edition. At this moment no project is in the final phase, but we are working on four new projects that have been accepted and for which we have built a team of author, translator, and two editors.

These projects are: Sobre espíritus y otros misterios/About Spirits and Other Mysteries (short stories), Esther Díaz Llanillo, translated by Manuel Martínez; Desde los blancos manicomios/no working title in translation yet (novel), Margarita Mateo Palmer, translated by Rebecca Hanssens-Reed; Rebaños/Flocks (poetry), Zurelys López Amaya, translated by Jeffrey C. Barnett; Un solo bosque negro y Las visitas (poetry), Mirta Yáñez, translated by Elizabeth Miller.

We also have projects by eight new authors under consideration, mostly in the genres of novel and short story.

Why only women, and in specific women living in Cuba rather than from the so-called diaspora?

Our society today has yet to evolve to a point where women have as many opportunities and as much recognition as men, and this is palpable in the publishing industry.

According to a 2013 study done by Vida, a U.S. based organization for women in the literary arts, there exists bias toward the publishing and the reviewing of books written by men. For example, of all the books reviewed in The New York Times in 2010, only 35{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de} of them were written by women. The truth is that literature written by women still isn’t considered regular “literature” but rather “feminine literature.” More books written by women should be published, reviewed, taught, and read. The entire Cubanabooks team is feminist (including our male colleagues) and we want to contribute to the fight for eventual equality in this sphere.

I want to clarify something: although indeed we prioritize the publishing of women residing on the island, last year we published a novel by Uva de Aragón, who resides in Miami. Uva argues that women of the Cuban diaspora face their own obstacles to being taken seriously, and still for me it is so very important to break down the barriers that have maintained such silence and misunderstanding between our two peoples.

What difficulties has your publishing house faced and how do you see the future?

We are an honest-to-God non-profit endeavor, whose work is done almost 100{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de} on a voluntary basis. For those of us who do this labor without any remuneration, such as all of us on the Cubanabooks Editorial Board, we have to keep doing the things that pay our bills. Those of us who live in the United States are full time university professors, and so it is difficult to find the extra hours required by our editorial duties.

For me personally it has been an enormous challenge to learn to make the transition from being a professor to also being an editor, a promoter, an organizational developer, etc. And just as with any literary press, funds are scarce.

Do you think the US market is ready for Cuban literature, now that the process of normalizing relations between the two countries is beginning?

Right now the U.S. public is hungry for information about Cuba, they are interested in hearing from people on the island, they want to come out of the almost complete ignorance that they have “enjoyed” for the last 55 years. A couple weeks ago, I was at the grocery store, and up at the register I was surprised to see that the most recent edition of Time Magazine was dedicated completely to Cuba!

How would you rate the literature written by women on the Island, from the perspective of an academic specializing in Cuban literature?

It is not for nothing that I have dedicated the largest part of my professional life to the study (and now the dissemination) of literature by Cuban women. There is an undeniable strength, a fascinating vitality, and an estimable level of culture and intellectualism in much of the writing being done by women on the island.

I think that Cuban women suffer from the same neurosis that we do in the U.S., because we have been raised to believe that we could do it all, but then we have continued to face insurmountable obstacles. The so-called glass ceiling. The ideas and emotions that arise from this tension are something that we share, but in addition Cuban women have a cultural heritage that is richer and more complex than ours in this country.

Moreover, I consider that having lived through the Cuban revolution has fostered in them a very complicated perspective. The writers whom I have studied, and whom I esteem the most, have achieved a narrative expression (or poetic, or both) that moves me deeply.

Tell me about yourself, your professional trajectory, how you began to work with Cuba, and how you would describe your relationship with Cuba now.

I finished my B.A. through my Ph.D. at the University of Texas at Austin (with a specialization in Latin American literature by women, under the advising of Dr. Naomi Lindstrom).

As a grad student I became interested in psychological approaches to literature, especially from the point of view of family systems theory. I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the representation of alternative family systems in narrative works by women from Mexico, Uruguay, Argentina and Guatemala. In particular, I was always fascinated with texts featuring LGBT characters (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender), with whom I identified personally.

It was when I was working as a lecturer at Stanford University that I went to Cuba for the first time, in order to participate in a women’s studies conference organized by Luisa Campuzano. A year after that I met Mirta Yáñez, and when I read her stories I came to the realization that contemporary Cuban literature and culture had been almost entirely left out of my university studies (with a couple rare exceptions).

With Mirta’s help, I became a Cubanophile. For many years I was concentrated on scholarly pursuits, and as a result my CV is full of conference papers and publications on diverse topics (family systems, LGBT, Queer Studies, literary humor, graphic humor, etc.) However, now I am much more intrigued by the amiable work of literary translation (I do limit myself to translating Mirta, and one Chicano colleague of mine, Antonio Arreguín Bermúdez), editing books for Cubanabooks, and teaching at California State University, Chico. Oh, and of course, the unending work of trying to change the world.

I try to go to Cuba at least every other year, and if there were more time and money (and less embargo) I’d be happy to go more.

Dear Sara E. Cooper

Very Happy Good Morning!

Hope you are fine!!

cordially thanks about that info.

i will continue contact for more info & FRIENDSHIP with Sara E. Cooper, now need Sara E-mail ID, Cell Number & details address.