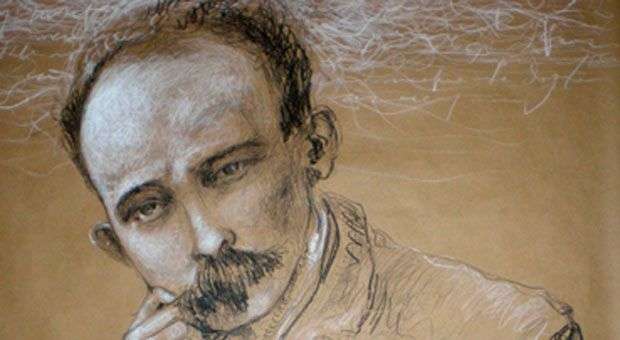

Martí on the verge of a return

After ten years of research, Froilan Escobar González discovered Martí on their lips, on the testimony of seven seniors who were children when they saw him land in Playitas and find death in Dos Rios.

You go to Martí in search of pupils. No matter what text of his you read, political, art, chronicles, instantly comes over emotion a person who recovers sight after many years must feel. In his metaphors full of nature, we feel the universe in a different way, as if it were true, and eventually our eyes, our senses all had been used to show the experience of living in an increasingly more opaque way. We come to believe then as Plato that locked in our bodies as we are, we perceive the world only imperfectly, we are only able to notice its shadows, and we have only a dim memory of light.

The written word of José Martí testifies to a soul always on the verge of exceeding the limits of the body, of a spirit that tenses physical pain and achieves sublimation beyond the stomach and daily miseries. However, creatures from another century as we are, it weighs on our admiration the doubt before that Martí that breathes and sleeps and walks among crowds being one among the many who populated his time. Discharge their responsibilities, then, the biographies, the testimonies of those who shared their calendar for maybe a little tear in the veil that separates the myth, the writer and leader from the man of bone and meat.

Looking for that Marti Froilan Escobar Gonzalez went out, for that Martí that in 1973 still belonged to the oral heritage, the intangible wealth of the elders of that time, however, knew him as a child. With the Apostle’s Campaign Diary in his backpack, he reviewed his journey from the landing at Playitas to transit to a new state of life (in which Martí believed) in Dos Rios. He found seven peasants who were over 90, and once, when they were around 10 years, shared a moment, just a few hours, with José Martí.

Suspicious like any good researcher of the quicksand memory is, Froilan Escobar walked again the 375 miles of the route. And so, ten years later, and after several conversations with the children who were then almost a century-old, he was satisfied.

Any bookstore (I was assured and saw it in effect) now hides in some of their shelves a copy with this evidence, gathered under the title of Marti a flor de labios. The book tends to get lost among many others due to a cover design that does not it do justice. If anyone undecided browses its pages and runs into the interior drawings, made by children, but poorly chosen, placed, and even repeated, might put it back. They will miss, however, the words that make it unique not only for the story that keeps of the hero but because they themselves are twisted in an exercise in language.

Froilan Escobar wanted to preserve the texture of the spoken word of the men and women born in the colony and privileged with the gift of adding years and experience. In this region of mountains and bush, the Spanish language evolves on the skirts, exercising itself and nature to take its own shape and it is for that comes as the bottle when is uncorked after a long time and satisfies a different thirst for drinking

The elders of the book were surprised by curiosity with which the Apostle wrote down their words quickly, as if they were in a position to instruct him. With inheritance of the seduction of his grammar, Marti on their lips merely crosses the border of a journalistic historical record to become a literary work, and we move away from the man to approach an unknown dimension of his myth

From grandparents to grandchildren stories passed on that Marti and Gomez that were there among them. Some kept very closely the presence of a tree where the president (so they said) rested, and when the powerful owner of those lands wanted to cut it down they refused, and when the money and the need brought lumberjacks from far who fulfilled the task, they held a funeral there as if it were a family member.

The seven older children that speak to Froilan Escobar, just need some fog away the years to meet the gaze of Martí. One of the girls says, “The stare of his eyes didn’t leave my mind, and that made me think, in my boy thing, that when he got up, he jumped directly from his eyes to the world, without having to put on shoes “.

On his smallness, his whiteness, the disproportion of his forehead, and rarefied Cuban accent that the president himself brought, they stay in love with his eyes like that wandering night flyers move chasing a sip of light. Do not we all do that when we read one of his texts?