Help us keep OnCuba alive here

If we want to be brief, the answer is “we don’t know.” Still, we can look at what has happened in other similar situations.

Last century there were three influenza pandemics. The one in 1918 was the deadliest. It developed in three waves: in the spring of 1918, in the autumn of that year and in the winter of 1919. The second one was really virulent and deadly, during which 64% of deaths occurred. In reality, the first wave was the least strong: it was responsible for 10% of the deaths from that pandemic. In the second wave, changes in the virus genome have been documented that could explain why it was more virulent.

In 1957, a new influenza virus appeared that caused the “Asian flu,” which also occurred in three epidemic waves: the first in the spring-summer of 1957 and with a relatively low incidence, the second in early 1958 and the third in winter between 1958 and 1959. Mortality was highest in the second two waves. Ten years later, in 1968, a new flu virus caused the so-called “Hong Kong flu,” whose spread was slower and more irregular: it started in autumn-winter in the northern hemisphere and was followed by a second wave the following winter with a higher incidence.

The last influenza pandemic, the so-called “influenza A” of 2009-2010, had less incidence and ended up having the effect of seasonal flu. In fact, this virus ended up adapting to humans and being one of the strains that have circulated every year since then. As we see, the second and third deadliest waves have previously happened with the flu virus.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the appearance of new epidemic waves will depend on the virus itself, on its capacity for variation and adaptation to humans. On our immunity, on whether we are really immunized and protected against it. And of our ability to transmit and control it.

Can the virus become more virulent as happened with the 1918 flu?

We don’t know. But, unlike the flu, SARS-CoV-2 is not the champion of variability. The influenza virus also has an RNA genome, but there are eight small fragments that can mix with other types of avian or swine influenza viruses, leading to new regroupings. Its mutation and recombination capacity is much greater, so influenza vaccines must be changed every year and pandemic viruses originate more frequently.

Since the SARS-CoV-2 started, the genomes of several thousand isolations have been sequenced and compared, and of course the virus mutates! They all do, but at the moment, as we expected, this one seems much more stable than the flu’s. Perhaps it’s because it has a protein (nsp14-ExoN) that acts as an enzyme capable of repairing errors that can occur during genome replication.

Therefore, although this definition of virus as a “cloud of mutants” is still valid in this case, for now SARS-CoV-2 does not seem to accumulate mutations that affect its virulence.

But, in addition, on other occasions it has been proven that viruses “jump” from one animal species to another, as in this case, over time they adapt to the new host and decrease their virulence. In other words, it isn’t always that a virus mutates to become more virulent, but generally the opposite. In any case, it will have to continue being monitored.

Are we immunized against this virus?

To avoid the spread of an epidemic, the virus transmission chain must be cut. This is achieved when there are a sufficient number of individuals (at least over 60%) who are protected against infection, act as a barrier, and prevent the virus from reaching those who could still be infected. This is what is called group immunity and is achieved when people have passed the disease or when they are vaccinated.

But we still don’t have a vaccine against this virus. Is there group immunity against this virus? Well it seems not. In the preliminary study on seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infection in Spain, one of the most important conclusions is that the national prevalence is 5%: some communities had a prevalence of less than 2%, while others exceed 10%. These data were obtained by detecting IgG anti SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using the immunochromatography technique, the rapid tests.

What they indicate is that, at most, in some areas, no more than 10% of the population has had contact with the virus. We are very far from that 60% or more, necessary to achieve group immunity.

But all this is much more complex than it seems. We still don’t know if having antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, that is, having tested positive in serological tests, really ensures that you are immunized against the virus. We don’t know, for sure, how long these antibodies last or if they are neutralizing, if they block the virus and protect you from a second infection. Neither do we have data on cellular immunity, that other part of our defense system that does not depend on antibodies but on cells and which is very important in overcoming viral infections.

It is true that, in the case of other coronaviruses, the antibodies last a few months or years and it seems they have a certain protective effector, but this may also depend on the person (the same doesn’t happen in all of them). It is also true that there are some plasma tests of patients cured of the coronavirus that is blocking the virus and have a beneficial effect in infected people, which would demonstrate that these antibodies are protective.

In tests with macaques infected with the virus, it has been confirmed that their antibodies do protect them against a second infection. But this has been done in macaques. It has also been suggested that having previous contact with other coronaviruses, the ones that cause flus and common colds, could have some protective effect against SARS-CoV-2. This has so far only been demonstrated in in vitro tests, but could explain the large number of asymptomatic people. Ultimately, group immunity remains a mystery.

Three possible scenarios

Taking all this into account, three possible models have been proposed.

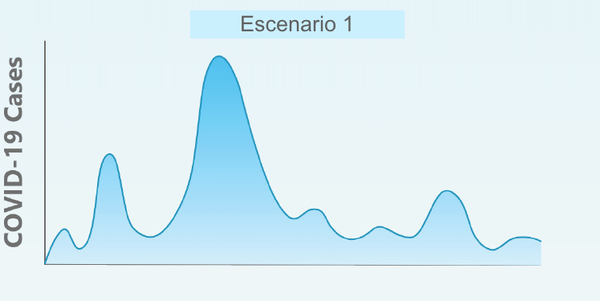

1) A much more intense second wave in the winter of 2020 followed by smaller waves throughout 2021. This scenario would be similar to influenza pandemics, but this coronavirus is not a flu, it doesn’t have to behave the same. This scenario could require reverting to some type of more or less intense containment measures during the autumn-winter to avoid again the collapse of the health system.

*Caption: Scenario 1

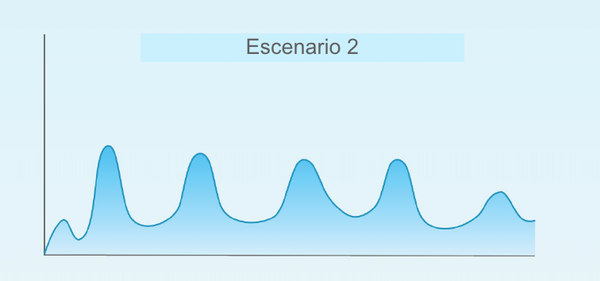

2) Several epidemic waves during a period of one or two years. This first epidemic peak that we have just suffered would be followed by repetitive waves that would occur consistently for a couple of years until they disappear sometime in 2021-22. The frequency and intensity of these fresh outbreaks would depend on each country’s control measures.

*Caption: Scenario 2

3) Small outbreaks of new epidemic waves without a clear pattern. This first wave would be followed by small fresh outbreaks that would gradually fade, depending also on each country’s control and containment measures. This scenario would not require reverting to such drastic containment measures, although the number of cases and deaths could continue for some time.

*Caption: Scenario 3

In any case, it seems that we cannot rule out that the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to circulate among us for some time. Perhaps it will end up synchronizing with the winter season and its severity will decrease. Even if there are no new epidemic waves, including a new respiratory virus that can have very serious consequences for a significant group of the population in the list of dozens of respiratory viruses that visit us each year is not good news. Every flu season saturates many hospitals’ emergency room, adding a new virus is a problem.

Control and avoid fresh outbreaks: being ahead of the virus

The virus has not disappeared. It can continue leaving deaths along the way. This is what is happening in other countries that had already finished their first wave before Spain, such as South Korea. Fresh outbreaks have also occurred in Spain in some cities during the start of the de-escalation. In most cases they have been related to population crowds (parties or family meals). But we cannot be eternally confined nor can we sterilize all environments.

To reduce the frequency and intensity of these fresh outbreaks, two actions are essential:

- On the part of citizens: avoid contagion. We already know how the virus is transmitted and that, fortunately, it is easy to inactivate it. Infections are more frequent in closed environments or with many people.

Let’s not forget: a lot of people, very close together and moving is the best for the virus. Avoid crowds, practice distancing between people, use masks, frequent hand washing, cleaning and disinfection (in that order), follow the health recommendations. This is what you have to demand of the citizen, we cannot relax.

- On the part of the health authorities: track the virus. We cannot continue tracking the virus as until now, we must take the lead.

It is necessary to establish a system capable of detecting an infected person at the slightest symptom, to be able to track and obtain information from their contacts, do a clinical follow-up on them and PCR and blood tests, and if necessary isolate them.

Detect an outbreak and isolate it. This requires personnel, equipment and diagnostic systems. And we must be prepared so that the health system does not collapse again. This is what has to be dealt with right now, to which all the resources must be dedicated, instead of doing massive tests to the entire population, to take “a still photo” of the situation. Decisions have to be made for sanitary reasons, not political. This is what we must demand of our governments, they cannot relax either.

If you have been in close contact without precautionary measures with someone who has had symptoms of COVID-19, within less than 2 meters for more than 15 minutes, you should isolate yourself for 14 days, and you should demand that the health authorities test the person with symptoms and you.

There may be a second or more waves, or maybe not. Now we have put out the fire, but we have not extinguished it, there are embers that can fuel the fire. The relaxation of confinement measures is not because we have overcome the virus, it is because we also have to save our livelihood. Very long confinement can also cause deaths. We aren’t going to end the virus; we can avoid it. We can mitigate its effects.

What has happened cannot happen again: this time we do have to protect the weakest. And that depends on citizens and governments.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.