During the 19th century, Cubans in exile were not exempt from socio-class determinations. Historical research has suggested a geographic settlement pattern based on the characteristics of that exile. A small group of supporters of the independence movement, wealthy and with enough accumulated wealth, settled in Europe. A second, made up of businessmen and middle-class men, chose the United States as their place of establishment, especially cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. A third, much more numerous and made up of workers, settled in the southern United States, especially in Key West and, a little later, in Tampa.

1886 marks an important year in many ways for the latter group. The abolition of slavery forced thousands of slaves on the island to join a labor force practically all at once. Some remained on their old plantations and experienced little change in their daily routines; others chose to migrate to towns and cities in the hope of improving their standard of living.

As a result of its whitening policies, between 1882 and 1894 the Spanish government continued to recruit Spaniards to establish themselves in “the always faithful.” Historians document up to 250,000 Spaniards arriving on the island during that period due to the policy of facilitating their mobility by paying for their tickets. As a result, just two years after slavery was abolished, around 1888, between the influx of former slaves into the labor market, the arrival of Spanish immigrants, and jobless white Cubans, unemployment in the Colony had reached epic proportions, the perfect shutter for the exit abroad of a motley mass of people.

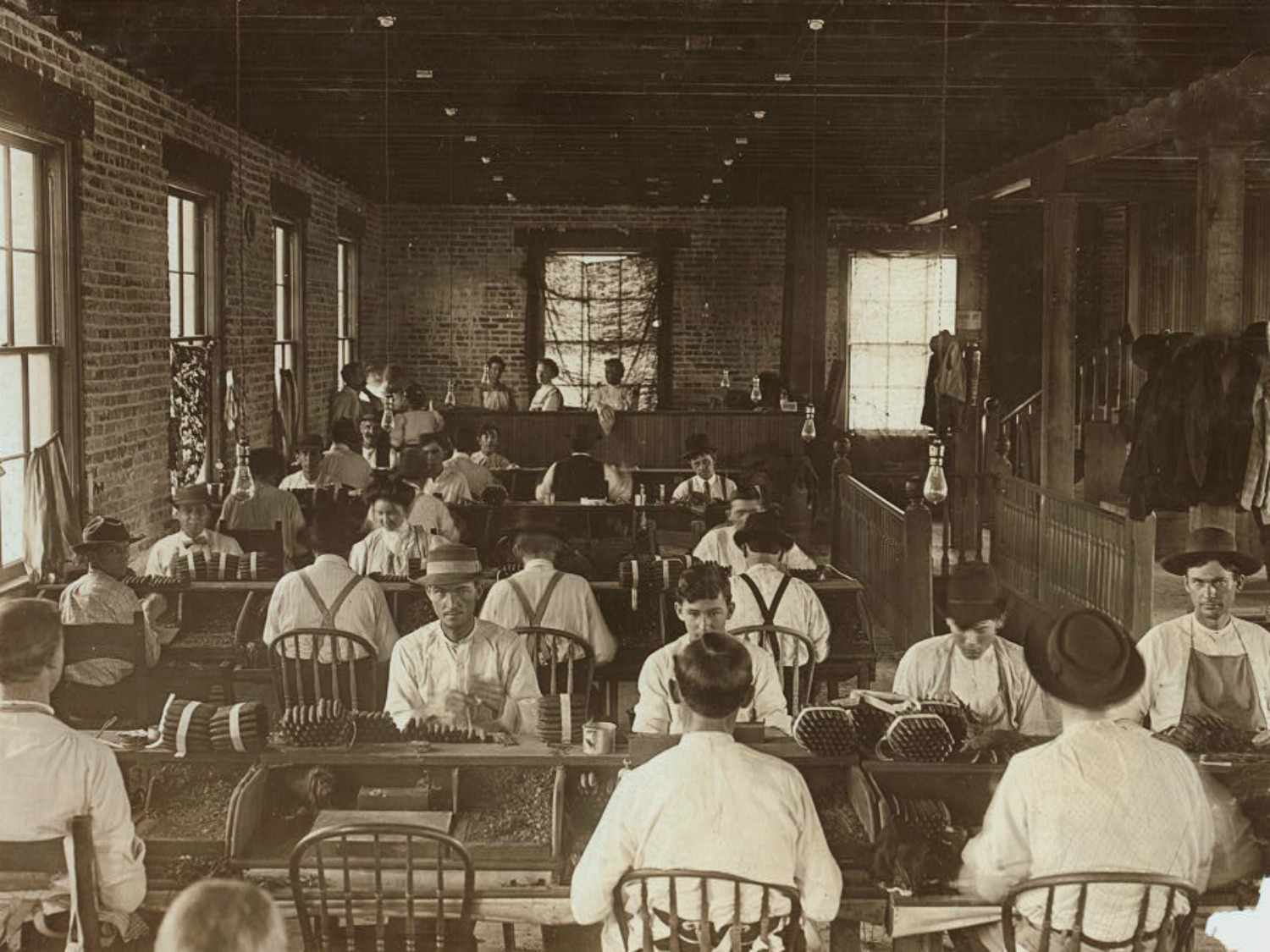

Indeed, starting in 1886, hundreds of Cubans, both black and white, began to move to Ybor City in search of work in the red brick factories, recently founded by the Valencian Vicente Martínez Ybor and his colleagues for the production of cigars. In fact, for obvious reasons they were initially the largest ethnic group in the Tampa Bay area with some 1,313 residing in Ybor City. Some came from Cuba and others from Key West factories, destroyed as a result of the great 1886 fire, the most devastating in the history of the town and that for twelve hours burned more than 50 acres and destroyed most of the commercial area.

Of the demographics of Ybor at the time, it is estimated that about 15% was made up of black-skinned Cubans. The nascent city was a true enclave that, at first, defied the segregationist practices of the American South. Black Cuban cigar workers worked “side by side” with whites and earned the same wages. Black Cubans and their families also lived among white Cubans and other European immigrants, all white. A testimony of the black Cuban Hipólito Arenas reaffirms this: “In those days, we grew up together. Your color didn’t matter, nor did your family. Your moral character did.” In the nascent Ybor City you could see people of all colors and ethnic backgrounds walking the streets, all mixed. And in terms of housing, another black Cuban testified: “In Ybor City you lived with an Italian next door and with a Spaniard and a Cuban on the other.” And another attested that in Ybor “there was no such thing as a white section and a black section.” They lived in the same neighborhoods and attended the same activities, including those called for Cuba’s independence.

In that group of black Cuban residents in Ybor at the beginning of the 1990s were the couple Paulina Hernández and Ruperto Pedroso, who with great effort and tenacity had managed to buy a piece of land and establish a rooming house on 12th Street and 8th Avenue, not far from the very center of Ybor. José Martí was taken to that place, currently the Parque Amigos de José Martí, by Paulina herself after the attempt to poison him on December 16, 1892. According to tradition, Ruperto was in charge of the personal security of the Martí, even sleeping in the hallway outside his room the entire time he was recovering.

From then on, Martí would decide to stay at the Pedroso house every time he was in Tampa. On May 29, 1894, he wrote to María Mantilla: “I have seen bad people and good people, and the good ones have been better than the bad ones. I have been sick and I was care for very well by Cuban Paulina, who is black and very ladylike in her soul, my doctor Barbarrosa, a man from Cuba and Paris and a good brother of the one you know.” They also say that after the attempt, Martí only ate food prepared and served by Paulina and that he always slept in the first room of the house. And that when he was in the house, its owners invariably placed a Cuban flag on the door. And that at night several groups of patriots gathered there to try to see the Martí, even until the wee hours of the morning.

A singular event occurred in the Pedroso house: Martí’s reunion with his poisoners, recounted by Paulina to Gonzalo de Quesada y Aróstegui and incorporated by Jorge Mañach in Martí, el Apóstol. According to this narration:

Ruperto made a move to throw himself at him. Martí restrained him and, throwing his arm over the visitor’s shoulder, locked himself in his room with him. After a long time, the other came out with bloodshot eyes and a taller face. When he had left, Ruperto reproached Martí for his trust.

“This,” he answered, “will be one of those who will fire the first shots in Cuba.”

So it was. Later historical investigations managed to identify one of the two “auxiliaries”: the Havanan Valentín Castro Córdova (1868-1924). Enlisted in an expedition led by Serafín Sánchez and Carlos Roloff arriving in Cuba on July 24, 1895, he ended the war with the rank of commander of the Liberation Army. Nothing is known about the other beyond the data that Mañach gives us in the sense that he also joined an expedition. The reason why both perpetrators decided to appear before Martí at the Pedroso house will remain another mystery.

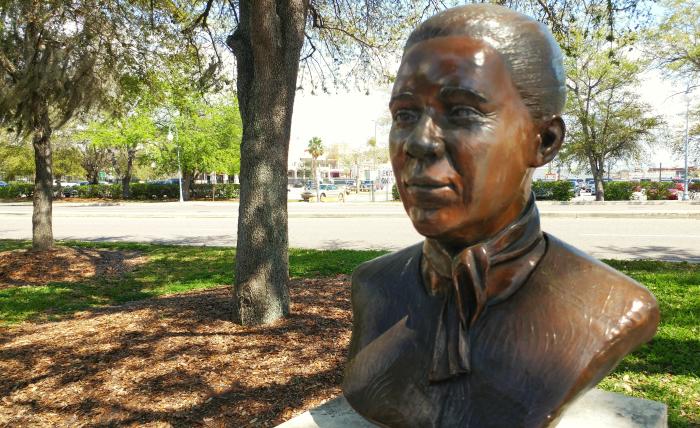

Paulina Hernández was born a slave on April 10, 1855 in Consolación del Sur, Pinar del Río, but her parents, of Carabalí origin, managed to buy her freedom. At a very young age, she managed to move to Key West, where she met Ruperto and they married. In 1892 they moved to Ybor City following the path of other Cubans. In 1897, on the second anniversary of Martí’s death, she wrote an evocation published by the Tampa newspaper Cuba: “Martí! I loved you as a mother, I revere you as a Cuban, I idolize you as a precursor of our freedom, I mourn you as a martyr of the nation. All blacks and whites, rich or poor, enlightened or ignorant, we worship you with our love. You were good: Cuba will owe its independence to you.” In 1910 Paulina returned to Cuba for health reasons, where she died three years later in the midst of neglect and poverty. They say that she asked to be buried with a photo of Martí in which he had written the following dedication on the back: “To Paulina, my black mother.”

In 1993 her name was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Illustrious Floridian women. And here in Tampa, on the banks of the Hillsborough River, there is a bust of her along with other personalities who contributed to the well-being, progress and culture of the city. The monument in the land where she was born is still a pending issue.

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court established the “separate but equal” doctrine (Plessy vs. Ferguson), which strengthened racial segregation throughout the country.

From this point of view, the enclave was over.