She is a director, playwright, poet, screenwriter and narrator. She works at the head of the La Franja Teatral interdisciplinary team, where she investigates and puts on works of documentary dramaturgy of which she is also the author.

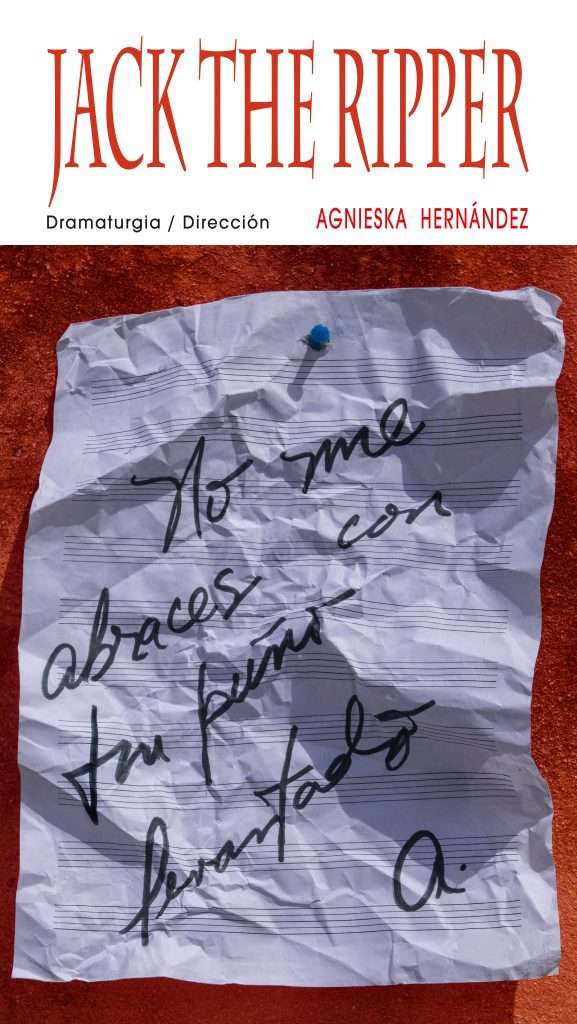

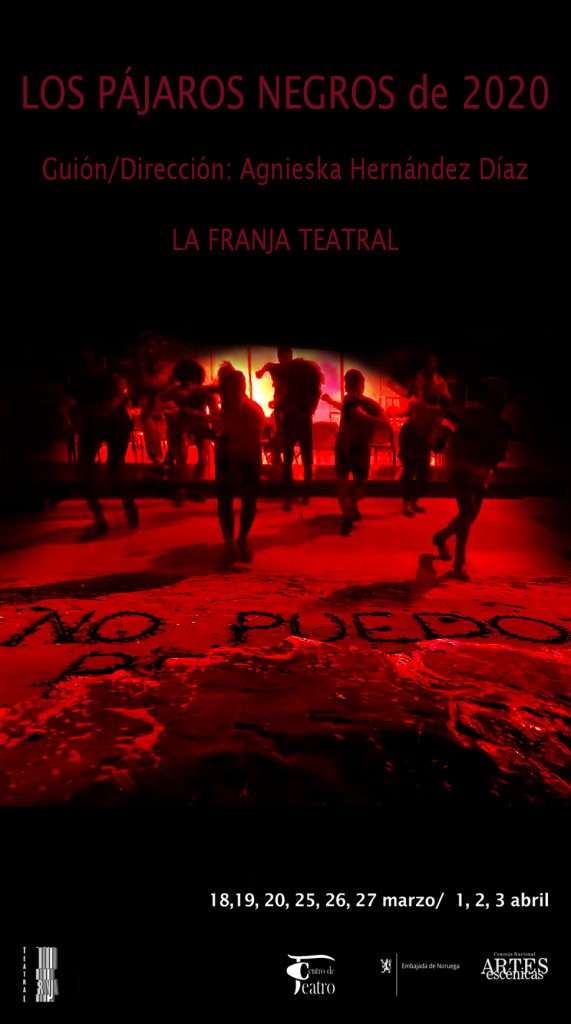

The Closest Farthest Away, Strip-tease, El año de Kalhil Madoz, Los días raros, El deseo Macbeth: fiesta documental, Harry Potter: se acabó la magia (documentary academy), Anestesia, voces urbanas, Kfé verde pero dulce, Personal training para subirnos la autoestima, Jack the Ripper: no me abraces con tu puño levantado, El gran disparo del arte, Made in china (entrenamiento de soledad), Los pájaros negros de 2020: training de razas and El diario de Ana Frank (apnea del tiempo), are some of her texts that have been brought to the stage in Cuba.

In 2016 she received the Critics’ Award for her book Documental de amenazas: posible dramaturgia, from the Tablas Alarcos publishing house. She is also the author of the volumes Se cambian objetos por historias personales; short stories, 2016, Loynaz publishers, and San Lunes (panóptico en dos estaciones); novel, 2009, Caja China publishers, among others.

Your professional resume does not state date or place of birth. Tell us about yourself. How and when did the vocation for writing arise? Inspiring first readings, people who stimulated or not your vocation. Does the vocation exist or is it a piece of the identity construction process?

Pinar del Río, 1977. I always lived with my grandparents. I loved them both, challenging them. I didn’t know that they were old, but they lifted me up like the old Simeon lifts the child in Rembrandt’s painting. My grandmother had first grade and my grandfather had taken a course at the La Conchita canned sweets factory. My house and school were only separated by a chain-link fence. I made a hole in the fence so that I could enter and leave the two spaces at any time. The teachers leaned out to drink water and began to congratulate my grandparents and ask their permission so that I could attend competitions and contests. The teachers, if they were going to be absent, left me the class plans.

My grandparents helped me get everywhere on time. Sometimes my grandmother took me. I didn’t know that she was old, but I suspected it because she was very strict. Sometimes my grandfather took me, after having had a shot of rum, but totally magnanimous, respectful and protective. They would wait for me on the sidewalk, in front of the Provincial Library. They listened to me read, sing, give my opinion, with enormous attention. I was a freckled little devil who didn’t give them even a moment of peace, but at 6 pm I would sit in the doorway to read piles of books that I don’t even know how they got to my house. I think it was my grandfather who rescued Noches blancas, Pobre gente, Las viñas de la ira, Las aventuras de Tom Sawyer, La Cartuja de Parma, El hombre mediocre and T.S Eliot from the trash. I fell in love with a verse by Brecht: “… I look like the one who carries a brick to show the world what his house was like.”

It was that. My wooden roof, my trees, my grandparents accompanying me to watch the movies, my bush of mamoncillo macho decorated with glass, my secret path to escape to the Galiano stream full of rot, pig intestines floating in the water, the mud cake that I could make in the rain, the yellow flowers on a tree that never had leaves, the sparrows falling from the ceiling to my bed, the bird’s nests, the arecas to hide, my chewing gum made on the grime of my hands when it is mixed with the flower of the Itamo Real. It was a jungle to awaken all the imagination of a girl, and also, I found a water faucet that was hidden in the second garden and the water tasted like Butterfly Jazmine flowers.

I felt like I couldn’t let any of that go. Every day I enjoyed my patio wanting to freeze those moments. I read eagerly and every afternoon I picked Maravilla flowers. The phrases that I marked in the books took hold of me. Whenever the opportunity arose, I would go to my mother’s work at the Provincial Court. I really enjoyed spending time with my mother and learned to type to help her write official documents that were inserted into inmate files. I exercised a whole protocol to transport information to the lawyers’ tables. Nothing made me more curious than crimes. I became invisible in order to spy on the trials and my mother explained to me that I couldn’t enter some trials that were behind closed doors.

The Court was a very special place, with marble stairs, and everything seemed a bit labyrinthine to me. Handcuffed men waiting for the judicial process were always seated on the benches in the corridors. They played balloons with me, handcuffed, and the policeman guarding them also played. Perhaps that is why I was so impressed when I read the chronicle “El Cristo de Munckácsy,” by José Martí. One day I discovered that there was a small bookstore in the basement of the Court, and I began to spend hours there. My mother bought me all the books that I liked, although later that economic issue cost a lot of fatigue. My mother’s calligraphy is beautiful.

And speaking of identity. Broadly speaking, how do you define yourself? What are you? How do you think you project yourself? How would you like to be?

Restless, but calm. Basic matters such as sleeping and eating bother me and that the body imposes elemental times of life on me with which I cannot negotiate because the day only has 24 hours, and it is never enough for me. I love being a woman and, like Simone, you learn to be one. Maternal with my daughter and with all the children and young people who may be close to me. Very concerned about the marginality that is spreading at full speed through our societies, concerned about the enormous defects that I detect in education and angry about the economic, ethical and cultural shortcomings of all kinds, which every day have worse consequences for the generations that are still being formed. I simply wish that the day-to-day in our country was not fraught with so much burden as a lifestyle and that we can heal a little.

You work various literary genres. Namely, poetry, narrative, playwriting. Can you toggle them all? Do you go from one to the other naturally? In general, poetry is a genre for introspection, while theater, as a stage event, is designed for collective experience. How do you know that this or that creative impulse demands one genre for its development and not another? Based on the attention you’ve received from critics, do you think that the playwright Agnieska overpowers the poet and narrator?

I go to poetry almost every day and I have dared to show it for a very short time. I always have a notebook, the dictionary, where I make poetic notes and I take the time to prepare each loose note well, because poetry is the generous mother that sustains all genres afterwards. Everything is poetry first. When I need to dramatically advance without losing power in the theater word, I go to my poetry notebooks and take it to pieces. Poetry defends us from long investigations that want to fully enter the pieces or the narrative. Poetry defends us from naturalistic dialogues. At this moment I dedicate more time to textual and spectacular playwriting, which are very different. I explore my possibilities from stage direction and other genres advance in parallel. I always have three Word documents open. I don’t turn off the computer. I cook and write. I rehearse with the actors and write. I check my daughter’s homework and write. I dye my hair and with the dye on, I write. I no longer wait for the ideal time of concentration because it does not exist.

When did you leave Cuba for the first time? What were your strongest impressions of that trip? Did it change your perception of the world in any way?

2008, London. Impressive, delicious. It scared me a lot that the books, the magazines and the information were in real time. I got so scared that I dropped a magazine announcing a concert for the next day because I got so used to outdated information that the commitment to participate in life in real time scared me. I cried in the garden of the Museum of Natural Sciences. Topics that our children take years to learn, or topics that we only learned after a semester in Medicine, are available there in a funny and didactic way for a European child to understand in a single Sunday. I put my hand on a column in the Museum to feel the effect of gravity. London was a first fresh air. In London I found a handle that you try to turn and the movement is never what you expect. Below the handle an inscription clarifies: “Nothing is certain except even a simplest system may show unpredictable signs of changes.”

In the first quarter of this year, two performances with your texts coincided on the Havana scene: Los pájaros negros de 2020: training de razas y El diario de Ana Frank (apnea del tiempo). In the first case you were also the director. They are two pieces where I notice, despite their marked differences, a certain aspiration to the so-called total theater. Is it so? I saw that in both cases the public reacted enthusiastically. Critics too?

I am the one who thanks the public and the critics for the reception of these pieces. I thank them for Ana and Shirley Temple, for Bill Robinson or the seeds of Mary Prince, for the raceless skin they brought to hug George Floyd and the children of the Lazaretto. But I thank them mainly because they find the works even though they are not yet published and do many beautiful things with them. These last pieces have been a life lesson. Each book and each piece build their own circulation or their ideal reader. Something in the pieces belongs to the author or director and to the team that raises and organizes them, but that experience that you take from the dust of the road and from the collective documentary that all of us have been since we were born, love, exchange, hurt and live, that documentary part people identify it instantly, it belongs to them and you can’t save it just in case one day, just in case a publisher, just in case a book….

I am also very grateful to the translators who have already approached and to the professors of Latin American and Caribbean Studies from various universities who today give importance to these small texts that we make from our geography.

In what way does your theater participate in the acute debates of contemporary Cuba?

Cuba is always in our pieces, even when these are not easy times to establish poetic dialogue with a society where there are notable material and communicative deteriorations, and multiple layers, stigmas, open wounds, and it is not easy to receive the public and forget who it is in this moment. I try to sow a poetic seed that helps us to be more tolerant or less racist or that helps us to look. Identification could terrify us, Aristotle. Or commiseration. If the theater cannot resemble its time, or if the theater could not open its arms to understand and offer a human opportunity to understand our societies in real time, then the theater would serve as entertainment for a little while and then it would be superfluous.

I’m going to name two renowned teachers: Harold Pinter and Raquel Carrió. How was your learning experience with them?

My first class with Raquel Carrió. I expected that class, but a copious meal of meats in strawberry sauce caused me to have appendicitis and the matter got complicated for a couple of weeks until they managed to restore my cerebrospinal fluid pressure. So, I missed teacher Raquel’s first classes. When she had me in front of her, along with two or three complications presented by my classmates, she dismissed us all so that we would have some time to think if we were really going to bother to write. All of us, in front of Raquel, seemed like a band of absent bums. I was very afraid that Raquel wouldn’t give us classes. Because Raquel is incredible and if you don’t go through her classes you will end up in the theater with duplicate characters, without learning internal and external structure and without grammatical synthesis for life.

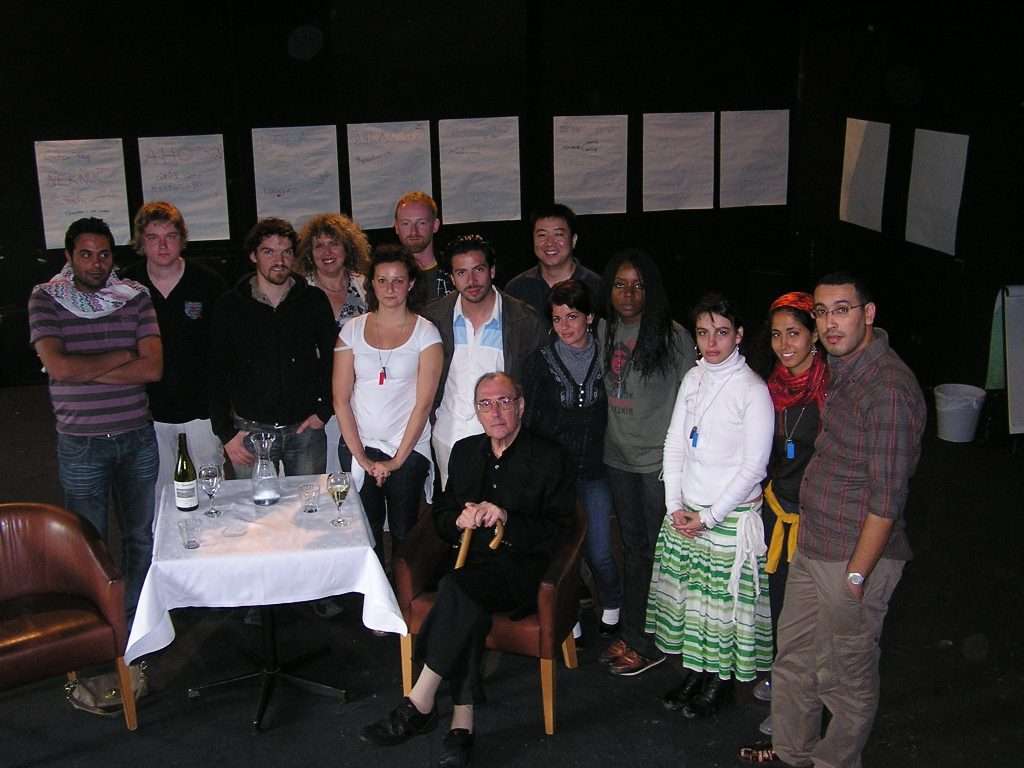

Harold Pinter, when he gave us a lecture at the Royal Court Theater, asked about the Cuban playwright and about the playwright from Morocco. Raquel Carrió and Harold Pinter were already immense teachers when I saw them for the first time. Calm and friendly voices that had already come back from the vices and evil of the world, and when those teachers look you in the eye they see your life and know if it is true that you are passionate about writing.

Is it true that actors are “difficult” beings? How is your relationship with them?

It is an ill-founded myth, perhaps, in small, televised egomania. Well-trained actors and young actors are extraordinary people, used to working in collective territories. When they like a creative process they grow amazingly from one day to the next, as no one else can. For actors to access all the vehicles on the stage, you have to know how to offer them the middle point where you guide them — never blindly — and also leave them free. Communication in clear, simple terms is important, while they are trying multiple combinations based on frailty; respectfully suggesting that they try what you already know they would have a chance to do and challenging them with a new version of themselves.

But, mainly, you have to know how they are before they come on stage, either to rehearse or to extend to the public. Then it is important to separate little by little and simply accompany them, entrust yourself to them, listen carefully to their point of view as an actor, as a person and as a generation. You have to know that every day is not the same or else the theater would not be alive and you have to understand that the energy of an actor is deposited in another actor and together they achieve the particular rhythm of each session. Never get tired of asking them to listen and observe the rest of the team. Sometimes they are so focused on the scene to come that they forget that one of the secrets to appearing alive on stage is simply staying tuned.

What can be expected from Agnieska in the coming months? Is there a long-cherished project that, for one reason or another, resists you? Do you want to talk about it?

I am seduced by the piece that is yet to be explored, the one that I still do not know. I’m trying right now to blur more and more the boundaries between the disciplines. I am passionate about everything theatrical when it is alive and an untrained part is saved that started today. Leaving the public a poetic key and forgetting at times about having all the stage control. Because we have been more trained to control the art than to dream from the possible arts. I already want to explore other poetic territories in which I have been working.

Share with us your poem that best expresses you.

Come in, the door is open,

wet from bleaching this time without seeing you

that makes me stammer words.

Tell me about yourself, I lived in an old house.

But on the ceiling the wood made drawings.

My dead. I put my arm.

When they stopped breathing, go deeper

when they stopped breathing,

I thought I stopped breathing too.

You and the sea. I imagine you in the sea. How shocking.

This weather makes me excited with your waves.

Why are we going to lie, it has not been so easy

neither to buy, or exhibit, or publish, or expect,

neither to trust or to realize.

The tip cannot be blunt. Nor the spear.

Why are we going to lie, it has been very good to write,

share the sign, sew and undo,

zigzag these lines.

Bursting from the center out.

Explode all the forces, the centripetal ones.

Wait, I light a cigarette,

in the end it’s just about the rhythm and one day I’m going to quit.

As in life, at this time you cannot become a balcony,

the sun

almost overwhelming.

At this hour I escape to the last step.

The ladder supports me.

No, the truth is, it can’t even support me.

Happiness has been all that will be born

in those baths with guava leaves that I give myself

because sometimes I’m a dog with rabies.

I missed you. Yes, I missed you.

At this hour it is not possible to become a balcony

Tell me about you, salty or with sugar.

The waves, how do you like them?

Little ones, or in a tsunami.

At this hour, bring me waves,

please. Go deeper.