One of the stories by Gabriel García Márquez that I find most appealing is Chronicle of a Death Foretold. I am not attempting to debate here whether or not it is his best. I am just saying that for me, that novel is like a more or less spectacular reflection of everyday life in any little town in Latin America and the Caribbean. Allow me to explain by recounting what happened to me one night in the late 1960s, in the old village of Guanabacoa, east of Havana. That night, my friend Alberto and I went to see a Western flick at the Carral movie theater, the biggest in town. Because it was a cowboy movie involving action and adventure, many other young people went to see it too.

Once we were inside and the film had begun, my friend Alberto said something about it out loud, I don’t remember what. Seated in the row in front of us was a trio of young friends, and I knew one of them: Pepe. He lived in my neighborhood. He had a reputation for being a braggart, and moreover he was a promising member of one of the most famous comparsas in the Havana carnivals of the time. In short, Pepe did not like my friend Alberto’s comment, and he even thought that it was aimed indirectly at him. Pepe turned around in his seat and angrily rebuked Alberto, and soon they began an argument which I luckily was able to pacify –interestingly, Pepe’s friends remained completely silent– thus complying with my elemental duty as one person’s friend and the other’s acquaintance.

When the show was over –the villain cowboys dead or in prison and the hero in the arms of his blond, chaste beloved– we headed for the exit and that is where Pepe and Alberto began arguing again. Right under the theater marquee, I had to intervene again to keep the two of them from brawling. But Pepe was not listening to reason: he wanted blood. Without a transition, as if it were a panning shot from a sequence, Pepe turned to me and challenged me in front of everybody, completely misinterpreting my good, peaceful intentions. Evidently, the role of “UN peacekeeper” was getting me nowhere. I couldn’t avoid it. Anything I said would have been viewed as pure cowardice. Pepe urged me to follow him to an “appropriate” place for fighting like men.

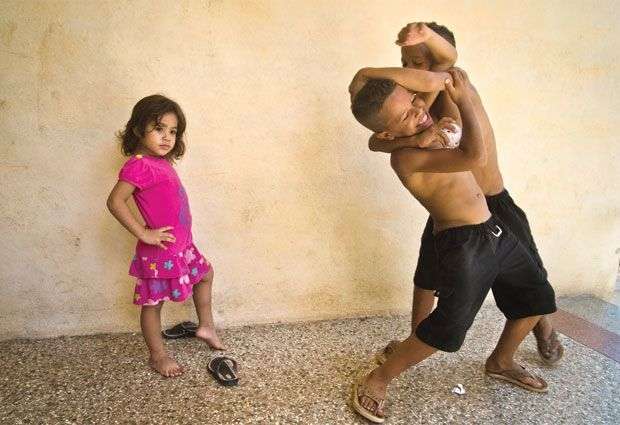

We walked a few blocks down to a street by the pre-university institute where Alberto and I were enrolled at the time. Nobody in the large audience that had exited the theater and witnessed the incident did anything to prevent the fight. It was an unspoken law in Guanabacoa that men settled their differences without interference. As I walked to the site of the “duel,” I wondered how I had gotten involved in the whole thing. It was I, and not Alberto, who now had to face Pepe. Now Alberto and Pepe’s two friends seemed like the “seconds” for this absurd match. Once we were at the “appropriate” place, face-to-face, the two of us became tangled up in a furious ball of punches, and in a few seconds we were rolling downhill –that solitary, poorly-lighted street was steeply sloped. When we reached the bottom of the slope and stopped rolling, Pepe was on top of me. Bad luck, I thought. I braced for the worst, but unexpectedly, Pepe stood up and offered his hand to help me get to my feet. When we were both standing face to face again, Pepe –who was a bit older and bigger than me, and who had a lot more street smarts than yours truly, a budding pacifist hippie– told me solemnly and sententiously:

—”Fine, now we’ve settled it like men.”

We shook hands and walked up the hill. There, our “seconds” were silhouetted against the dark curtain of night. After we reached them, each group went its own way. I didn’t say a word to my friend Alberto as we walked to the bus stop. It seemed to me unjust and disloyal of him to do nothing to stop that absurd, fleeting fight, for which he himself was responsible to a certain extent. But I also couldn’t help thinking about the strange precepts of my surroundings, my immediate culture. That encounter had been a faint imitation, a caricature, of a street fight. All that mattered was the game of appearances, the social camouflage, to comply with that particular town ethic, which I would encounter again years later in the pages of Chronicle of a Death Foretold.