One of the results of the historic relationship between the United States and Cuba was the existence of an entire infrastructure to transport merchandise and persons, a history that can be traced back in time and which reached its highest point in the 1940s and 1950s.

Toward the first half of the 20th century, the changes in communications and means of public transportation made it possible for a substantial increase in the transportation of passengers, in as well as outside the United States. There were, for example, more trains and lines connecting Key West to Tampa, New York, Washington DC, Chicago and other points of the Union, at times in an express way for a hop to Cuba: a train and ship combo. That was what President Calvin Coolidge used to attend the 6th Pan American Conference, held in Havana in 1928. Moreover, there were more ships devoted to the “smokeless industry,” phenomena all related to the greater availability of free time of persons as a consequence of the reduced workday and more vacations.

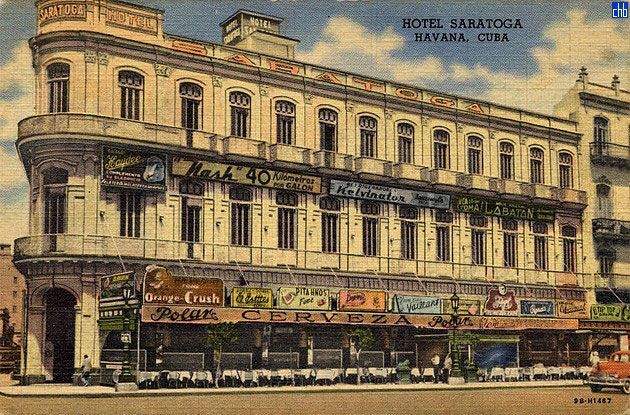

As a destination, Cuba combined two insular dimensions: exoticism – a different culture and language – and proximity almost at the reach of your fingertips, which was sealed from the beginning. Colonial buildings with the imprint of Spanish domination: patios with vegetation of Moorish echoes; an architecture that won it early on the description of “the Paris of the Caribbean,” with a Central Park and nearby comfortable and luxurious installations: the Sevilla Hotel (1908), the Plaza (1909), the Parkview (1928), the Saratoga (1933), in addition to the Inglaterra (1856) and Telégrafo (1860), plus an enviable climate, far away from the cold in Boston, Chicago or New York. In December 1930 came the jewel on the Loma de Taganana: the Hotel Nacional, in charge of the U.S. firms McKim, Mead & White and Purdy & Henderson Co.

The Key West-Havana links are full-blooded, and therefore full of capillary vessels. Initially the key was a territory subordinated to the island’s Captains General. But even during the British possession of Florida something peculiar occurred: the Spaniards called it “the North of Havana” and issued licenses to fish there, return to San Cristóbal and sell the catch in the markets. In 1815, the Governor of Havana legally deeded it to Juan Pablo Salas, an outstanding military officer in Saint Augustine, Florida, an authentic exponent of Spanish picaresque: he sold it twice, the second time to U.S. businessman John W. Simonton for the equivalent of 2,000 pesos, an arrangement that, according to stories told, took place in a Havana café.

With its definitive belonging to the Union established in 1822, Key West was also a place for the settlement of Cuban migrations before, during and after the 19th century wars, and especially for cigar makers, collections and patriotic sermons. And even of rocks taken to the other side of the Strait: one from the Demajagua sugar mill and another from the old Havana wall, just like in Tampa there are six royal palm trees planted in the six former provinces, located in a park where the house in which the José Martí of “With all and for the good of all” lived.

On May 19, 1913 a historic event took place: the first flight between Key West and the island, piloted by Agustín Parlá Orduña (1887-1946), born on Key West of exiled and hardworking Cuban parents. The hydroplane, which flew without a compass, landed at sea in Mariel carrying an element of deliberate and deep patriotic content: the flag that José Martí had used during his travels through Florida while he was collecting funds among the poor of the earth. Finally, the wings had won. And they would arrive to stay.

Eight years later, in 1921 Aereomarine Airways – a merger of two companies – started daily flights to bring / take post and passengers between Key West and the island, an initiative that for lack of another technology included the use of messenger pigeons to be able to warn land in case of mishaps or accidents. It was a fleet of hydroplanes – three, baptized as La Niña, La Pinta and La Santa María – that landed at sea in front of the Malecón, close to the bay, before the curious and awestruck eyes of the people of Havana, who saw in those powerful floats another expression of a modernity initiated during the first intervention and deepened during the Dance of the Millions, with its splendors of El Vedado and its spectacular automobiles making noise in the streets. A spectacular leap, since the trip between both points was reduced to an hour and a half in the clouds.

In full Prohibition, which shot up not only the number of U.S. tourists but also of bars in Havana, these flights were known with a programmatic label: Highball Express. In 1928 Pan American Airways, Inc., founded a year before, inaugurated the first line of Key West-Havana commercial flights with seven passengers on board a three-engine Fokker F-7 (NC53), which landed in Columbia airport on January 16. From then on, its daily flights departed from over there at 8:00 am and returned at 3:45 pm. Twelve years later, in 1940, Pan American Airlines, which had inaugurated its operations in 1927, got to have a service of 28 daily flights to Cuba at a cost of some 45 dollars for the round-trip ticket.

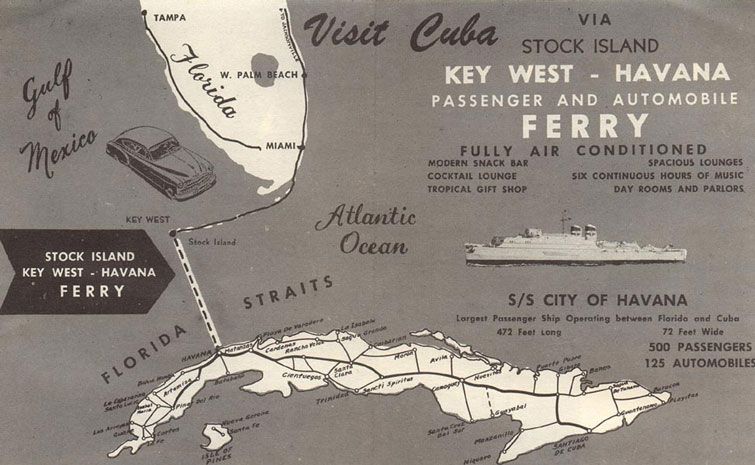

Meanwhile, the ferries had continued their development. In 1956 a super attractive move would be implemented: the automobile ferry service, that is, the SS City of Havana, built in 1943 for war purposes, just like it had occurred with the Model 75 hydroplanes of the 1920s. The novelty consisted in transporting passengers with their cars from Key West to Havana at a cost of 23 dollars per person and 76 per vehicle; the ferry arrived three times a week and had capacity for 500 persons and 125 cars. This was what allowed tourists to drive through the city with those “big cars” that appear as testimony in the photos of the 1950s, added to those that the elite and the middle classes bought in installments in the agencies, some on La Rampa and its surrounding areas.

In 1916, around 113,000 U.S. tourists visited the island as a consequence World War I, which for obvious reasons banned Europe for U.S. travelers. Already by the late 1930s different excursions organized in the United States transported to Cuba – and especially to the capital – thousands of tourists. According to the National Tourism Commission, 86,270 tourists and 76,982 passengers in transit visited Havana in 1930, for a total of 163,252 persons, most of them from the United States. According to the report of the Commission for Cuban Affairs, in 1935 both categories of visitors had left in the country 12,591,000 dollars, a figure only surpassed by the incomes from sugar and tobacco.

The 1950s were a boom: the first year of that decade saw 194,000 travelers land on the island; seven years later they already amounted to 356,000, from all classes and social groups, in keeping with a moment in which tourism had been more democratized in the United States when the prices for transportation and accommodations went down due to a buoyant economy and the specific strategies of the market and competition.

Moreover, the U.S. people had in their favor certain customs and migratory facilities. According to Havana. The Portrait of a City (1953), by Jamaican writer W. Adolphe Roberts, they could visit the island without a passport. A tax receipt or a driver’s license were more than sufficient, a privilege they shared with the Canadians, British and French (the others had to present to the authorities their passport stamped with the visa and the round-trip ticket). The automobiles entered free of taxes for a period of 180 days, and circulated with the plate from their own state. The drivers were only issued a temporary driver’s license.

The ferry, property of West India Fruit & Steamship Co., Inc., suspended its operations on October 31, 1960.

The arrows had already been shot.