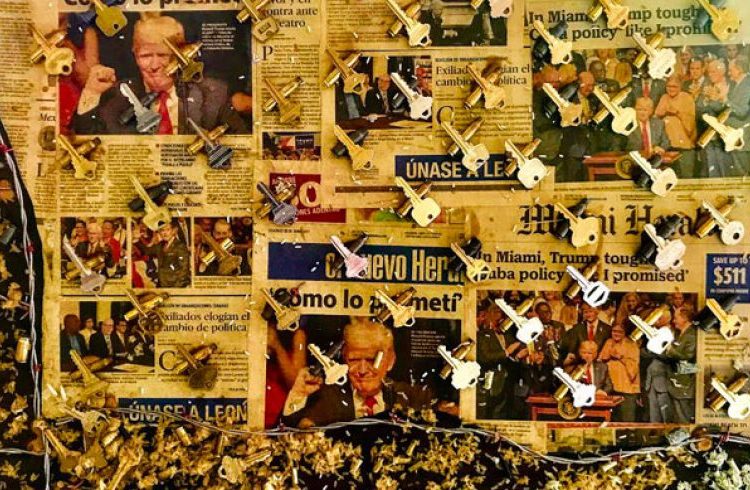

Donald Trump’s speech in Miami rejecting the rapprochement with Cuba not only displayed his lack of information about the island but also the flaws of some arguments used in the liberal press to defend Barack Obama’s policy. By accepting the debate terms, from the total condemnation of the Cuban Revolution by the anti-normalization right wing, the liberal position for starters gives three of its most forceful reasons against the embargo/blockade: the moral, the legal and the historic.

Christopher Sabatini’s opinion commentary “Trump’s Imminent Cuba Problem” and “U.S.-Cuba Policy Change Advocates: This Is Your Ally?” together with “A Cynical Reversal on Cuba” by The New York Times editorial board are typical examples. They reject an intensification of the embargo, but attribute to the U.S. Cuba policy and the sanctions advocates a moral authority for their opposition to the Cuban government, which is not justified by the conflict’s history, or its position toward human rights as international legal norms.

A THIRD ROAD WHICH ISN’T ONE

Sabatini says that “the argument that embargo toughness is equal to human rights and political change is seriously and morally flawed on a number of levels, historical and logical.” However, the “middle ground” he proposes and his arguments are instrumental to promote the same end purposes of the embargo; the imposition – now through peaceful means – of a vision of Cuba created in Washington or in Miami that denies any legitimacy of the Cuban Revolution, considered by Marco Rubio “an accident of history.”

As part of that logic, the December 17, 2014 opening to Cuba is useful because it undermines the Cuban government, allows for negotiating security and counter international crime agreements, and opens business opportunities for U.S. citizens while promoting the emerging private sectors of the Cuban economy and the opposition groups related to a change of regime. Sabatini tells us that “either way Cuban citizens lose” because Raúl Castro will give priority to tear gas, rubber bullets, electric cattle prods and other instruments of repression. That way he accepts as valid the main fiction used against the Obama policy: U.S. cooperation with the Cuban government must be minimum since there is a drastic separation of the government as a usurper of sovereignty, and the Cuban people represented by the opponents, and the U.S. administration of the moment’s chosen ones. The role of the United States – in that fiction – is to bring freedom to Cubans.

Sabatini separates President Obama’s policy in a “brilliant” dimension exemplified with his speech in Havana, and another “shameful” one represented in the White House statement apropos the death of Fidel Castro. Obama barely defined Fidel Castro as a complex figure whose role in the history of Cuba and the world would be defined in the future. Sabatini does not explain his “middle ground” but it would have been a diplomatic blunder to condemn the leader of the Cuban Revolution since it would intensify conflicts among Cubans and between Cuba and the U.S. The lights and shadows of the Revolution are specific to the policies implemented in each area and it corresponds to the Cubans of each period to assess them without totalitarianism.

It would be unfortunate that all that was advanced in the last Democratic administration in the understanding of the weight of nationalism in Cuban policy, and the need to respect Cuban sovereignty as it is conceived by international law be lost now in a Faustian accommodation with the embargo advocates. One of the most immediate political challenges related to the issue of ideology for the upcoming Cuban leadership in 2018 is the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the 1959 revolutionary triumph, and what to celebrate: The end of the Batista dictatorship? The vindication of sovereignty in the face of the wrongful U.S. intervention in domestic affairs? Of course. The installation of a state-run and single party economic model? Much more controversial. Barack Obama’s choice to let Cubans resolve these dilemmas of the past while the thawing in his last month in government advanced speaks well of him.

The sneakingly defense of détente avoids vindicating two glorious moments of the vision of Cuba, as an opportunity and a country in transition, not as a threat to the United States. In South Africa, Obama behaved with the dignity of a Democratic super power. He greeted Raúl Castro, with no concessions to Cuba but rather to the historic reality of the island’s role in the struggle against apartheid. A human rights struggle in which the embargo advocates headed by Jesse Helms and the Cuban American National Foundation were on the wrong side.

Obama’s statement on the death of Fidel Castro respected the reality of a complex personality. The same Castro government that organized the literacy campaign and other social measures that have opened political participation to millions, systematized the exclusion and reclusion without a fair and impartial trial of supposed social misfits for ideological reasons and, at a certain time, even sexual orientation. It is a complex legacy in human rights in which the best the United States can do is let Cubans judge themselves, promoting empathy and a vision of the future. The leaders of South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Algeria and other countries would have been ungrateful if they hadn’t gone to Fidel Castro’s funeral to give thanks in person for the sacrifices of the Cuban people.

The other major moment in human rights between Cuba and the United States under Obama was the collaboration in West Africa against the ebola epidemic. Obama did what was ethical, not just what was in the interest of the United States. In the face of the embargo advocates who defended a criminal position against a cooperation that saved thousands of lives, Ambassador Samantha Power spoke proudly of advancing in common interests and values. It’s not about an issue of right or left, but rather about what is correct.

Cuba and the United States can cooperate without having to agree on the bad practices in human rights of the respective governments. International law encourages criticizing human rights violations but based on regulations and multilateralism, not with unilateral sanctions. The international system of human rights only makes sense in frameworks of respect for international law. The manipulation of human rights advocates is respected when the way in which international law establishes its promotion is ignored. The United States has to accept international law as the appropriate framework for its relations with Cuba. Just as Cuba must accept the international agreements on human rights as the legal framework for relations between the government and its citizens.

EVERYTHING EXCEPT HUMAN RIGHTS: THE EMBARGO / BLOCKADE ON CUBA

The blockade/embargo was never a human rights policy but rather its negation. Its codification into an act was the momentous work of Jesse Helms, a defender of Southern racism against Afro-Americans and Latinos, an enemy of civil rights in his own state. When Trump proclaims the return of that unfair “act” he restricts the rights of U.S. citizens. Eliminating that policy is not just a question of businesspeople, military, and lobbyists, but rather of the priests in the churches, the environmentalists, the physicians and professors, of the moral majority of the U.S. people in general.

The pro-embargo lawmakers from the South of Florida are in favor of Trump’s restrictions for most of the U.S. citizens to travel to Cuba, those who no longer find the morality to persuade their own Cuban-American voters. That undue privilege granted to a group of U.S. citizens over others is immoral.

The embargo advocates denounce that not all U.S. citizens who travel to Cuba dedicate themselves to denouncing the deterioration of the healthcare system and the arrest of dissidents. In search of balance, Sabatini criticizes U.S. tourists in Cuba for cruising in 1950s cars, indolent about the problems of the Cuban people. What is the immorality? None. What’s right is that every traveler to Cuba or to any part of the world exhibit sensibility for the host country’s culture, history, and politics, but this behavior is cultivated with persuasion, not with restrictions. The correct policy for the United States is not achieved by drawing a diagonal of the parallelogram between the lines of the embargo advocates and its opponents. There are positions that are irreconcilable. If the embargo is a violation of the human rights of the Cubans and the Americans, it should be denounced as such.

Sabatini explains how we Cubans are going to be freer of communism by receiving more U.S. travelers. I agree with his view, but I admit that perhaps it won’t happen like that. About what there is no doubt is that the day that the embargo ends, we Americans are going to be freer and more coherent to practice the freedoms we predicate. That example is the best contribution that U.S. democracy can make for the democratization of Cuba.

The first maxim of an ethical policy – and all promotion of human rights necessarily has to be ethical – is to not do harm. The use of sanctions is considered a legitimate tool to condemn human rights violations, but just under specific regulations. The sanctions against Cuba do not meet those parameters of international law. They are unilateral, condemned by all the global and hemispheric multilateral agencies, and in violation of the sovereignty of Cuba and third countries. They include medicine and food, aggravate the situation of the population in general and have no end clause that forces a periodic assessment of its validity and impact as the UN Security Council established for Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait and discovery of mass violations of international law against the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

The discussion about sanctions directed at specific violators of human rights, codes of corporative social responsibility, or aids with democratic conditioning lacks relevance if the point of departure is the general punishment of the Cuban people and the government’s capacity to implement the progressive carrying out of several rights like healthcare, food, education, and others. Everything that can be done in cooperation with the Cuban government, particularly with its modernizing sector, must be endeavored. Obama put an end to the incoherence of sending Alan Gross to provide secret access to the Internet while in the United States the Cuban government was forbidden from buying equipment for that same purpose. For the first time since 1959, the U.S. official position seemed to not be against the Cuban government or people, but rather in favor of observing international standards.

I agree with Sabatini in that the Cuban government has generated resentments in the Cuban community abroad and among the Cuban people for injustices it has committed and commits. Those traumas did not occur in a void. None of those violations must be justified to understand that the Cuban Revolution operated in a context hostile to its sovereignty. There are legitimate complaints against Cuba like Cuba has legitimate complaints against the United States. Cuba gave refuge to fugitives from U.S. justice after the United States did not respect the 1904 extradition agreement between the two countries by giving refuge to criminals of the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship, which it backed until barely a few months before its overthrow.

Nothing positive can come out of a version of good and bad guys in the conflict between the United States as a big power and Cuba – the neighboring archipelago in the Caribbean that is no one’s backyard – where it is urgent to have an atmosphere of cooperation. Foreign policy is not the ideal space for a therapy of catharsis. As a big power, it is realistic that the United States endeavor that Cuba accommodates its behaviors to an international order under it hegemony. But such an objective will not be achieved by choosing favorite Cubans or punishing institutions like the Cuban armed forces.

Faced with the generational transition in the Cuban leadership in 2018, the United States must try a friendly relationship with all of Cuba’s sectors, including the Armed Forces and the intelligence services. Promoting democracy and human rights is to help processes and requires guarantees, not choosing favorites in the domestic policy of a sovereign State. The pro-embargo activists are not human rights activists.

To the extent that U.S. respect for Cuban sovereignty allows it, with the foreign normalcy must come to the domestic normalcy. A country under foreign siege cannot be asked for a democracy of peace. In the same way, a country in normal conditions has no urgent pretexts to not respect the human rights of its citizens as it is conceived in the international agreements. If that were the case, there’s where the interests of the Communist Party of Cuba would begin and those of Cuba would end.

Since in politics sequencing is important, what it understands as most urgent is prioritized. The end of the embargo, whether it strengthens or not the Cuban government, would surely unhamper important dynamics of liberalization and reform in Cuba that today, while that U.S. policy against Cuban nationalism exists, are tied up. The nostalgic travelers of the 1950s or those who prefer to prioritize the defeat of the embargo are not the immoral ones. They neither execute nor promote the violation of any human rights.

If someone is missing clarity it is those who call the embargo advocates “pro-human rights activists.” Those who invoke democracy only on Sundays to criticize the Cuban government because it prevents the ladies in white from parading while they ride roughshod over so many human rights of Cubans, U.S. citizens and citizens of third countries every day of the week cannot be called that.