At first, the U.S. political class did not seem to be convinced of the need for Florida. For some, it was a “gloomy and pandemic region, only made up of arid waste”; for others, it was a “swampy, low, excessively hot, sickly and repulsive terrain”; not a few thought that the United States should leave it to the Indians and the mosquitoes. A place, in short, not conducive to “founding a city on a hill,” far from Matthew 5:14: “You are the light of the world.”

Before the second half of the 19th century, Tampa was economically irrelevant and population-wise underdeveloped, but a series of subsequent discoveries and undertakings progressively contributed to revitalizing the panorama and its social dynamics. In 1883 the discovery of phosphate — a strategic material for the production of fertilizers — in the region of Bone Valley, to the southeast, would bring about a first wave of prosperity, reinforced by the creation three years later of the Peace River Phosphate Company.

After several unsuccessful attempts, Henry Bradley Plant (1819-1899) and his Southern Florida Railroad entered Tampa in late 1883 with tracks to central and western Florida. The businessman bought the contract to build the vital stretch of the Jacksonville, Tampa, Key West line from Kissimmee to Tampa. When he completed 70 miles of new track in early 1884, Tampa was connected to the rest of the East Coast with the subsequent increase in ease and efficiency of railroad travel. Ultimately, it would connect fabulous Tampa Bay to the national rail system, enabling inbound and outbound commerce. The railroad also facilitated the subsequent evolution of tourism.

In 1884, in a true fact-finding task, Spanish civil engineer Gavino Gutiérrez (1849-1919) entered Tampa looking for guavas together with Cuban Bernardino Gargol for the latter’s canning business in New York. They did not find them, but from Tampa they went straight to Key West with information about the land and the new local infrastructure developments. They met with Spanish producer Vicente Martínez Ybor (1818-1896) and with another famous businessman from the tobacco industry, Ignacio Haya. The message was clear and distinct: Tampa was located in a privileged place, with a formidable bay, ideal temperature and humidity, decisive requirements to achieve a flourishing tobacco industry without the inconveniences existing in the key and in New York, basically worker strikes that did not lead to prosperity for the business.

It would then be a matter of buying land at well-negotiated prices with that Board of Commerce, building housing for the workers and factories in an area near the port, which would greatly reduce transportation costs. A very well thought out operation that in an impressively short time paid off. The first and most important, an industrial city that emerged almost as if by magic precisely from the swamp, the mosquitoes, the crocodiles and the miasmas.

By 1880 Tampa was a sleepy town of about 720 inhabitants. Eight years later it came to have one of the largest populations in Florida, with a prominent presence of Cuban cigar makers and their families. According to the 1892 Census, the same year West Tampa was founded, conceived by Scottish-born lawyer Hugh Mcfarlane (1851-1935) to compete with Ybor City, 2,424 Cubans lived here out of a total population of 5,532 inhabitants: almost 44%. A historic change: “In the final years of the 19th century,” writes Lisandro Pérez, “Ybor City became the first Cuban community in the United States. The 1900 Census found that 3,553 people born in Cuba resided in Hillsborough County, in which Tampa is located. It was the largest concentration of people born in Cuba, surpassing New York.”

A population, on the other hand, with a distinctive diversity, made up of Spaniards and Italians — the latter originally coming mainly from a couple of small Sicilian towns — and also Germans, Scots, Irish and Americans, both white and black. In short, a true multicultural center whose implications reach to this day.

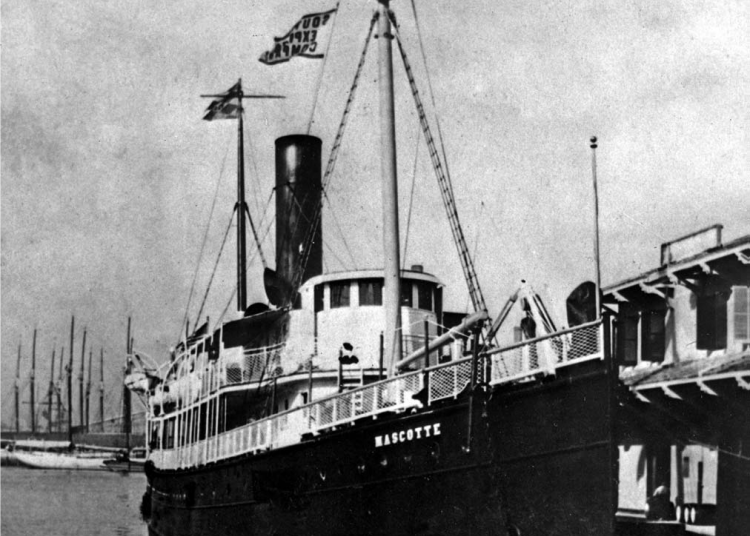

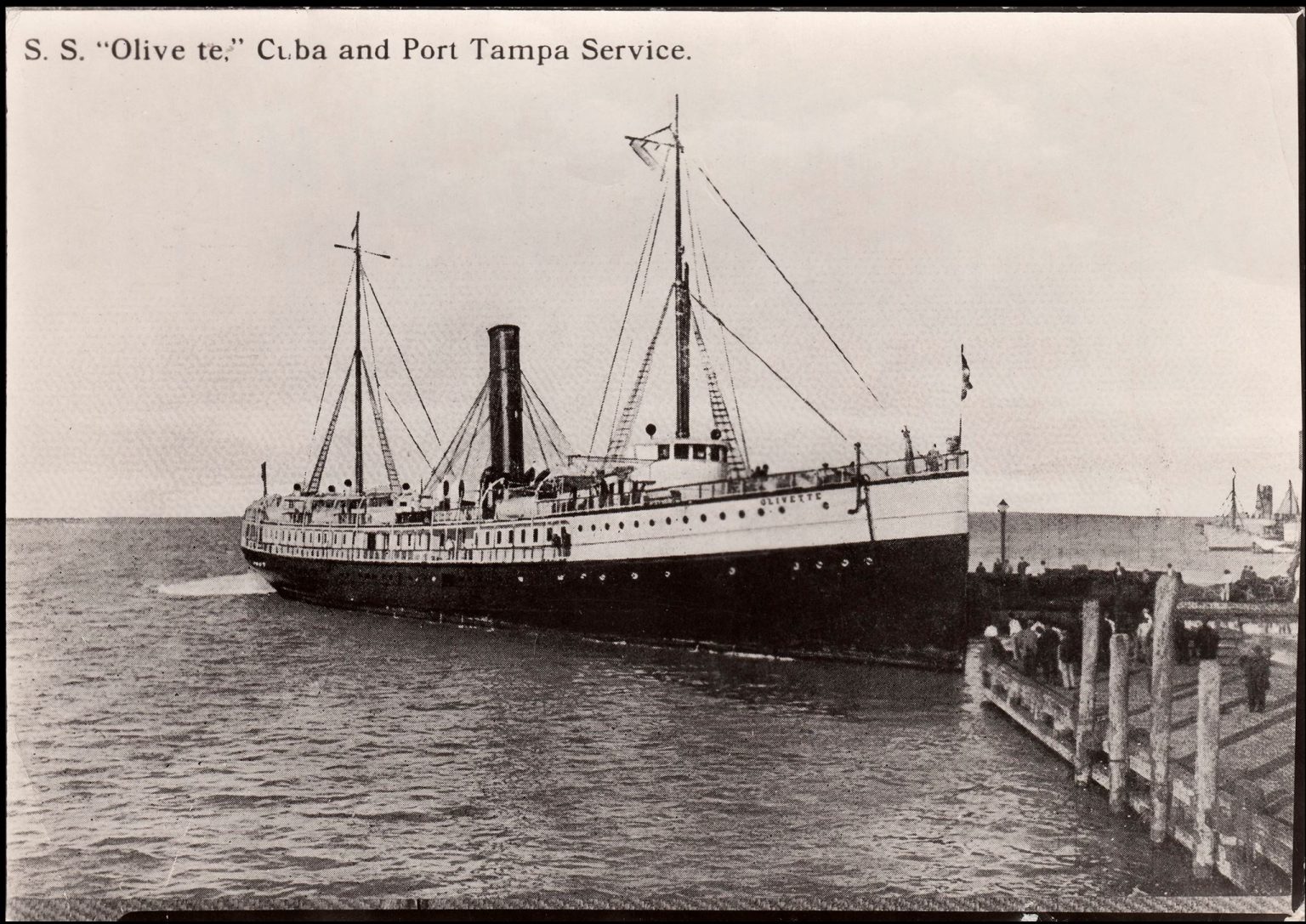

But this development of the tobacco industry would have been practically impossible without other chapters of infrastructure. In June 1888, Plant himself had inaugurated the voyages of the steamers Mascotte (884 tons) and Olivette (1,611 tons), which moved between the port of Tampa and Havana with a stopover in Key West. On board came the tobacco leaves from Vueltabajo to feed the factories in Ybor City and West Tampa. But there was also the human factor: cigar makers and workers arrived from the island fleeing from the war and looking for a better life and conspirators from back and forth. The uprising order for the war of 1995 arrived on the island on the Mascotte, brought by train from New York to Ybor City by Gonzalo de Quesada and finally hidden in a cigar made in the factory of the O’Halloran brothers, in West Tampa.

At the beginning of 1896, General Valeriano Weyler declared an embargo on tobacco exports from Cuba to the United States, hoping to force the closure of the factories in Tampa, true centers of conspiracy permanently watched by Spanish diplomats and spies. According to historian Karl H. Grismer, in his Tampa: A History of the City of Tampa and the Tampa Bay Region of Florida, Vicente Martínez Ybor and other tobacco industry executives persuaded Plant himself to send the Olivette and Mascotte to Havana before the deadline set by the Spanish to implement that embargo, in order to be able to bring in enough tobacco to keep his factories running. And they did.

The Mascotte and the Olivette covered the route between Tampa and Havana for about 25 years. The Olivette was shipwrecked in January 1918 during the cyclone that hit Havana. The Mascotte ended her days as scrap iron.

In the 1920s, the seal that would characterize the city of Tampa was designed using an image of the Mascotte. But here comes the misunderstanding: instead of a steamer, it represents a sailboat, undoubtedly selected for a majesty that has nothing to do with the humility of that original little steamer.

But it has remained that way to this day.