At a meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), at the end of January 1968, Fidel Castro would explain the Soviet pressure on Cuba, using the oil supply to achieve the island’s alignment with Moscow. Going back to the background of that situation, he would share with the Central Committee (CC), for the first time, the secrets of the “October Crisis.”

Relations with the USSR had left a mark on the difficult process of Cuban political unity. Before the missiles, the pro-Soviet current originating from the People’s Socialist Party (PSP) had provoked the crisis of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI), just a few months after its constitution in the summer of 1961. The 1962 political current called sectarianism would reemerge in 1967, with the name of microfraction. This time, it would do so with a connotation of national security: his direct link with the Soviet embassy and with others from the socialist camp in Havana.

In the same meeting of the CC, Raúl Castro would read the detailed report on “la Micro,” as the Cubans have named that current since then. According to Aníbal Escalante and his group, the government was taken over by “a strong anti-Soviet current” that represented “the petty bourgeoisie” bent on “moving trade to the capitalist areas” and making “Cuba go back to the system that had been swept away in January 1959.” And he postulated “that the USSR is the country that should lead the hegemony” in the world socialist movement.

In addition to a “current of ideological opposition to the Party line,” they were engaged in “conspiratorial activities,” consisting of “approaching Soviet, German and Czechoslovakian officials and citizens,” “government representatives,” “journalists close to the CC of the CPSU ,” “MININT advisers,” “in order to convey their points of view and create a state of opinion in the leadership of these parties,” to promote “political and economic pressure by the Soviet Union that would force the revolution to approach that country.”

In his meetings with “la Micro,” Rudolf Petrovich Ajliapnikov, Chief of the KGB advisers in the Ministry of the Interior (MININT), had affirmed that “in Cuba the conditions were created for another Hungary to take place.” And that “the petty bourgeoisie was even inside State Security.”

As curious data, the petty bourgeois of reference were, none else than Che Guevara, Haydée Santamaría, Raúl Roa, Alfredo Guevara, Celia Sánchez, Armando Hart, Faure Chomón. On the other hand, among the 43 defendants in the “Micro” process, were Ricardo Bofill, and others from the Socialist Youth and Cuban Maoism, who would later become dissident militants.

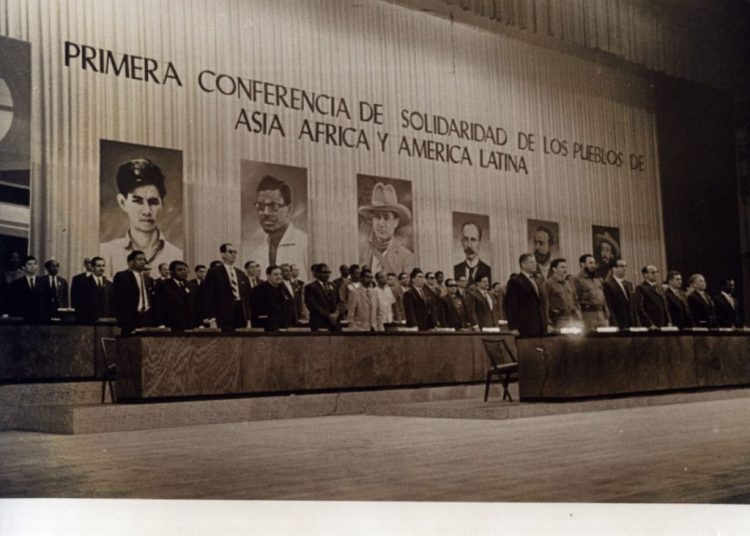

As Aníbal would acknowledge in his mea culpa before the PCC leadership: “The key to most of the group’s ‘displeasures’ lies in the ‘international question.’” Specifically: in the role of the USSR and the role of Cuba. That dichotomy had become very evident just two years before “la Micro” broke out, when the Tricontinental Conference was held in Havana.

According to the declassified archives of the OSPAAAL, the Cuban delegation considered that the USSR and China had turned the movement into an “arena of confrontation.”1 For example, the United Arab Republic (Egypt), under Nasser, was aligned with the USSR, in the same way as Guinea; meanwhile, Pakistan, North Korea and Indonesia did so with China. Although the governments of the USSR and China were not part of the solidarity organization of Asia and Africa, their “non-governmental organizations” were, so they were the two largest delegations, and those that had the means of their governments to attract followers.

Among the States and liberation movements opposed to Soviet and Chinese hegemonism, there were, in addition to Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, Algeria, the fronts of South Vietnam, South Yemen, Palestine, Mozambique, Guatemala, South Africa, which were fighting at the time. Likewise, the Latin American and Caribbean delegations that did not advocate armed struggle, such as those headed by the socialists Salvador Allende (Chile), Heberto Castillo (Mexico), John William Cooke (Argentina), Cheddi Jagan (Guyana), and those from Uruguay, Costa Rica, Honduras or Haiti.

Some pro-Soviet saw the Cuban position against the USSR as a factor of division. According to declassified documents from the archives of the East German Statsi, the Cubans “adopted an attitude of superiority towards the other delegates and even disagreed with the USSR, and intrigued against the representatives of the Latin American communist parties, as well as avoiding the presence of the USSR in the speeches and the drafting of documents.”2

This Cuban-Soviet relationship was crossed by elements that made it more complex, especially military cooperation. In the same Raúl Report on “la Micro,” he recognized that “advisors, specialists and technicians of all kinds have worked with us in the armed forces, thousands of Soviet officers and there is not really a single complaint to give about them.”

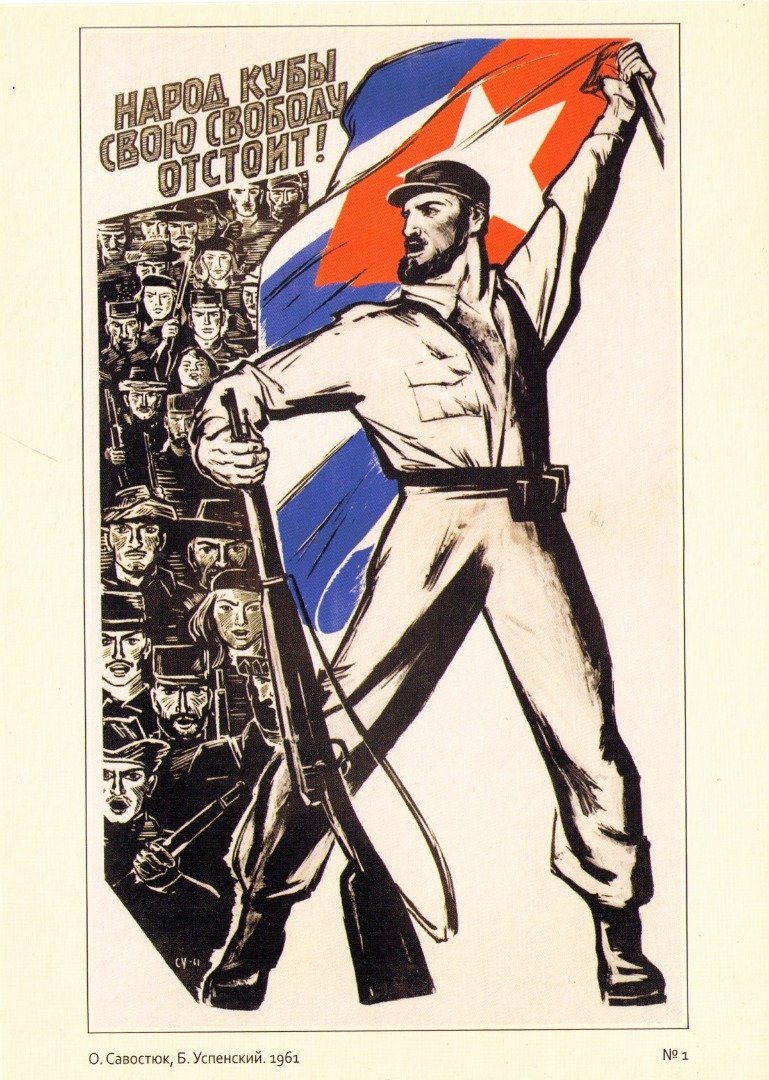

That cooperation also had strategic significance for the USSR. Barely two years after the Crisis, the Soviet radio-electronic monitoring station had been set up in Cuba, where the University of Computer Sciences (UCI) is now located. Intelligence experts have estimated that this station could collect three-quarters of the information Soviet intelligence collected each year. Cuba benefited from that strategic information, exposed as it was to U.S. hostility. Without the need for that cooperation, the Cuban reaction to the invasion of Czechoslovakia on August 23, 1968 cannot neither be understood.

Among the most cited and least read speeches by Fidel Castro is the one dedicated to that event. Many remember the part where he justifies the intervention for a realpolitik reason: the preservation of the socialist camp’s integrity. They forget, however, the criticisms that characterize the rest of the speech, both directed at Moscow and at Prague.

The first of these criticisms is that the intervention can only be explained from a political point of view, not a legal one. “None has signs of legality.” There has been “a flagrant violation of the sovereignty of the Czechoslovakian state.” He only recognizes the Warsaw Pact countries “the right to prevent a socialist country from falling apart and falling into the arms of imperialism.” Nowhere does he describe it as an expression of internationalism or anything of the sort.

The second brings together a set of substantive political objections to the “popular democracies” of Eastern Europe. He says that “the youth in Eastern Europe are not educated in the ideals of communism and internationalism”; that they suffer from a condition of “ignorance about the problems of the underdeveloped world”; as well as “dogmatism,” “bureaucratism,” and not being “truly revolutionary.” Finally, he describes his relationship with Moscow as “unconditionality,” “satelliteism,” “lackeyism.”

The harshest of all the criticisms is directed at the inconsistency of the USSR in the face of U.S. aggression against Vietnam and Cuba: “Will the divisions of the Warsaw Pact also be sent to Vietnam if the Yankee imperialists increase their aggression against that country and the people of Vietnam request that help? Will Warsaw Pact divisions be sent to Cuba if the Yankee imperialists attack our country, or even, in the face of the threat of an attack by the Yankee imperialists on our country, if our country requests it?”3

When Warsaw Pact troops entered Prague, a change of administration in the United States was three months away, and a hawk like Nixon was likely to win the next election. If a former member of the administration that spawned the Bay of Pigs invasion reached the White House, would it not occur to him to return Moscow’s intervention in Czechoslovakia with a blow to its ally in the Caribbean? At the height of the U.S. aggression in Vietnam, USSR military supplies to Cuba were crucial.

On the other hand, Moscow was also concerned about maintaining access to the “Cuban hill” on the very southern U.S. border. According to declassified Soviet documents, Brezhnev himself appealed to Fidel to discuss their differences, following the “rules of relations between socialist parties and communist parties” (April 1967). The USSR came to fear that the increase in Cuban relations with the West, in particular with France, could alienate Cuba, and make it seek another partner. In this way, he offered him new credits and agreed to the nonfulfillment of the commitment to deliver sugar in 1968.

These are not precisely reciprocities for having justified the invasion of Czechoslovakia, because according to professor and former diplomat Juan Sánchez, “a part of the Soviet leadership [criticized the Cuban position] for ignoring the right of the USSR to maintain what was conquered in World War II.”4

A quarter of a century later, the end of the USSR and the abrupt cut in economic and military relations — including the withdrawal of the radio-electronic station — contributed to the crisis called the “Special Period.” Since then, the differences between relations with the USSR and with Russia are so many that it is not worth listing them. However, all of the above is still inscribed as a fundamental reference in Cuban foreign policy.

Those who find “irony” in the current Cuban position on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict could take responsibility for this story. Those who affirm that we are continuity, too. If this policy has principles, it is not because it is tied to a doctrine, to a set of apothegms, but rather to practices dictated by a specific historical and geopolitical situation: to integrate a community of nations that refused to align themselves with great powers, be they capitalists or socialists, and that at the same time, they require alliances that compensate for the fatality of the space that they were assigned, in the face of the hostility of their main neighbor. For example, Vietnam.

In this series, I have tried to show that, for Cuba, the October Crisis is not a simple episode of the Cold War, but a key in the architecture of its foreign policy. Having refused the inspection of its territory when the missiles were withdrawn, after a negotiation in which it did not participate, as well as the continuation of low-flying flights over its territory, were not rhetorical gestures or outbursts of wounded pride, but practices of sovereignty, which did more in favor of the application of international law and stable peace than most treaties.

This story not only shows that being in the geopolitical space of a power, in its “sphere of influence,” does not entail assuming submission to its dictates. It also documents that Cuba did not seek to wage war against the United States, nor did it ever join an enemy military bloc, nor did it align itself in favor of nuclear proliferation in the region. The history of the “Missile Crisis” shows under what exceptional conditions of imminent threat the country accepted the placement of the missiles.

Teaching classes, I have verified that my students from the U.S. — including Cuban-Americans — have learned that the geopolitical conflict dates from Castroism (and anti-Castroism), rather than from the founders of independence. They have also acquired the notion that Cuba was an unconditional ally of the USSR and aligned itself with the Warsaw Pact. Interpretations such as these judge as “ambiguous” a policy that characterizes the current Russian intervention in Ukraine as “the use of force and non-observance of legal principles and international norms that Cuba subscribes to,” and that reaffirms its opposition “to the use or threat of force against any state.” According to these interpretations of what Cuban policy should be, a “clear” position would be to defend Ukraine’s right to join NATO militarily, and its far-right government. Failure to do so is equivalent to denying the concept of self-determination attributed to Cuba.

From this flat interpretation of the history of relations with the USSR-Russia-Ukraine-etc., metaphors emerge, such as “Ukraine challenges Russia with the same spirit as Cuba challenges the United States.” Or that “the invasion of Russia will be like the U.S. invasion of Vietnam and Iraq.” Such comparisons assume that not joining the anti-Russian bloc is equivalent to isolation, as if China, India, Vietnam, Iran, South Africa, had not done the same, and did not appreciate self-determination. And it takes for granted that this Cuban position will have repercussions in relations with its main interlocutors and allies in Africa and Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Finally, it argues that this position will give rise to the continuation of the blockade; or even to a U.S. intervention on the island.

History shows, however, that the end of the USSR and the deployment of Cuban troops in Africa, more than 30 years ago, did not move the relations of the “North” with the island one millimeter. It also records that when Che, three months after the Bay of Pigs, proposed to Richard Goodwin, JFK adviser, a dialogue on “Cuba’s foreign relations” (with the USSR), the response was to tighten the screws on the Revolution. On the other hand, progress in bilateral relations, under Carter and Obama, has occurred precisely when the island has been less alone or distanced from allies such as the USSR or Russia or China.

In the end, U.S. policy has helped bring its two main Cold War rivals together; and has made it easier for Cuba to strengthen its relations with both at the same time as never before in 60 years. We will see how much this landscape changes, when the smoke of war dissipates.

Notes:

OSPAAAL. Historical archive. Análisis general de la Conferencia Tricontinental. January 1966. Drawer No. 1, Archive 1.

GDR archives. Folder: SAPMO-BArch DY30/J IV 2/2/1045 Protokoll Nr. 6/66 (Einschätzung Politbüros ZK SED Drei-Kontinente Konferenz 310) January 1966.

Fidel Castro, Análisis de los acontecimientos de Checoslovaquia, Havana, Ediciones COR, No. 16, August 23, 1968.

Juan Sánchez, “Las relaciones cubano-soviéticas en 1968 vistas desde Cuba,” Temas magazine, 95-96, 2018.