The practice of abortion in Cuba is legal and has been institutionalized for more than five decades. This is how it appears established in regulations and protocols of the Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP), among them the regulation associated with the current Health Law, in force since 1983. Thanks to this and to other historical, social and cultural factors of longer standing in the country which cannot be ignored either, the collective perception of the voluntary interruption of pregnancy on the island can be considered as mostly positive, although there has been no lack of questioning and resistance from conservative and religious sectors, which have been gaining visibility and influence in the heat of the public debates about the Constitution and the new Family Code, and which have vigorously disputed the rights included in its wording.

In this scenario, as we underlined in a first approach on the subject, the Cuban authorities have assured that they intend to take a step forward and shield the right to voluntary abortion in a new legislation, after years without changes in this regard and in the midst of an international context — and, in particular, in the American continent — marked by legal advances and setbacks, and by heated controversies between supporters and detractors of this procedure. This was recently confirmed by the head of the sector, Dr. José Ángel Portal Miranda, at a press conference before accredited media, in which he stressed that this decision seeks to address the “advancement of fundamentalisms and conservatisms that in the world and in the region are putting at risk a fundamental conquest of women’s health.”

In his speech, the minister also highlighted the policies and strategies applied since the 1960s with the aim of providing Cuban women with safe and free access to this practice in health institutions on the island, as a way to support “women’s body autonomy, life and health,” and avoid maternal deaths due to risky and unsafe procedures. All of this, he said, as part of the institutional accompaniment to “conscious” family planning, in which abortion is assumed “as a last resort in the event of an unwanted pregnancy” and not as “a contraceptive method in itself.” However, he acknowledged that what has been established on the subject “can be improved” and that, even with the plans implemented and the “discreet trend” towards the reduction of these procedures in recent years, the volume of voluntary abortions in the country continues being high and the authorities have the purpose of reducing it “to the essential minimum.”

With Portal Miranda’s statements as background, and taking into account the current context on the subject and other associated aspects on the island, we spoke with researcher and activist Ailynn Torres Santana, doctor in Social Sciences and columnist for OnCuba, who gave us her assessments on the future and current scenario of voluntary abortion in the Caribbean nation, and delves into the issue of the necessary legal support for this right of Cuban women.

What are, in your opinion, the right decisions and mistakes of government and institutional policies implemented in Cuba in recent decades in relation to voluntary abortion?

The main right decision is to ensure a safe and free abortion, as well as to institutionalize it in a general way and ensure women this right. The second thing is to treat it as a public health issue, which is something of great importance because it also allows distancing the regulation from the content of abortions as a moral or other issue. That seems to me to be a relevant achievement that, however, does not escape challenges and insufficiencies. This happens, for example, in the case of contraceptive coverage, an aspect in which Cuba is above other countries, the region and the so-called global south, and that is key because abortion cannot be thought of without at the same time thinking in access to contraceptives, nor can it be thought of without the guarantee of other sexual and reproductive rights.

So, regarding contraceptive coverage in Cuba, it has increased tremendously over the last few decades, but even so it is insufficient and in recent times it has been even more insufficient. There is a lack of access to contraceptives of different kinds and especially to condoms, and that is a mistake for public health policies, a very important problem in relation to sexual and reproductive health in general, which has an obvious connection with the issue of voluntary abortion.

In relation to mistakes, I would say that the procedure of voluntary interruption of pregnancies not infrequently also involves acts or processes of gynecological violence, which is an issue that has been discussed in Cuba in recent times, both by institutional as well as non-institutional voices, and that has also begun to be discussed within health institutions, which is something that seems good, necessary, but which has as its counterpart that the gynecological and obstetric protocols and procedures have not been updated at the level of the political and scientific discussions there have been in this regard. These debates have to do with safeguarding the comprehensive health of patients, both physical and psychological, because many times when undergoing these procedures, women face processes of violence in different instances that can derive from the naturalization of the procedure. Sometimes the issue of abortion is not handled by placing the patient at the center of the process and thinking of it as a comprehensive health issue, in which aspects related to mental health must also be considered, for example.

And to close with the mistakes and insufficiencies, there is the issue of the need for effective and comprehensive sex education programs. Although these programs exist in the country as part of institutional policies, they are insufficient in terms of quality and also in terms of effectiveness. And that is a problem. Not for nothing the feminist slogan around this issue refers to three things that are closely related: abortion, sex education and contraceptives. So, in these three fields we can find good decisions and mistakes in Cuba.

What has been, from your perspective, the social and cultural impact of the abortion policies implemented in the country, both for women and for society as a whole?

One important thing to keep in mind is that the social norm regarding abortion in Cuba changed drastically, of course, after 1965, when this practice became institutionalized, but it was already subject to greater acceptance and legitimation throughout the 20th century, because we know that since 1936 there was a flexible interpretation in the country of the norms related to abortion and, in fact, many women from other countries, including the United States, came to Cuba to have abortions. So, the fact that this happened, that since long before the 1960s it was already considered that way, it turned out to be fertile ground for the greater normalization and greater legitimacy it has achieved in Cuba in terms of social norms.

Likewise, if one were to analyze the issue more precisely, it would be necessary to attend to the different sub-periods, because although the voluntary interruption of pregnancies was institutionalized in the 1960s, the regulation of this procedure has not always been the same. There have been periods with more bureaucratic barriers or other situations and mediations for access to the service, with which we could roughly say that there has been an institutionalization that progressively normalized this practice within the social norms and also facilitated, within the health institutions, access to the procedure, although there are differences in the way this has been expressed over time in the institutional structure.

And in terms of social impacts, we would not only have to think about women and society in general, but also, for example, how much legitimacy there is in the practices of voluntary interruption of pregnancies in particular for medical practice and for health professionals. In other words, the normalization of abortion as a legitimate practice reaches a large part of Cuban society, women, of course, and also other specific groups that have a particular involvement in the issue, such as the medical association and the overall health institutions.

Can one speak of legal abortion in Cuba? Or only institutionalized abortion?

In Cuba, abortion is institutionalized and regulated; that is to say, it is in norms. The most important, let’s say, is the regulation of the Public Health Law in its article 36, which speaks of ensuring services of voluntary interruption of pregnancies. And, in addition, it is in the methodological guidelines of the Ministry of Public Health. At the same time, abortion is not illegal, it is not penalized, with which we could say, according to a legal interpretation channel, that if something is not illegal, because it is not established by law as such, then it is legal. However, it is a different thing to say that abortion is legal, because abortion is not part of a law in Cuba. It is regulated, but it is not specifically in any law, because the Public Health Law does not speak directly about abortion, although the regulation of that law does.

How to reconcile the right to voluntary abortion with a low birth rate scenario like the one Cuba is going through?

Cuba is a country that has been facing the aging of its population for several decades now, that is not new. But this population aging and the stimulus to the birth rate have not generally been expressed as a restriction to the policies of voluntary interruption of pregnancies. The stimulation of the birth rate has gone through other channels, through regulations related to employment, to care, but it has not directly implied a restriction of the institutional service of abortion.

This, however, does not mean that there are no problems in accessing services for voluntary interruption of pregnancies. Recent research has shown, for example, how people who do not live in the provincial and municipal capitals have difficulties accessing these services, because, for example, they do not have transportation to reach the institutions where the procedures are performed. And the existence of manifestations of corruption to speed up access is also known and, since the interruption of pregnancies is a procedure that, moreover, has a specific time — so it does matter if you do it today or if you do it within a month —, it is essential that access to this service not only imply that it is available there, but that the channels through which it is reached and each of the steps that must be taken to finally end up in the interruption of pregnancy be really effective, viable, agile.

In general, in a context of low birth rates and demographic aging, discussions on these issues should be independent of discussions on abortion. Therefore, they should not influence them, because sexual and reproductive rights — and, specifically within them, the right to voluntary interruption of pregnancies — must be ensured in any circumstance: with a high or low birth rate, with a high population aging or in a different scenario. In other words, this is a right that pregnant women have and that is independent of the demographic trends and political processes of nations.

You previously referred to existing insufficiencies regarding sex education in the country. In your opinion, what is the importance of a coherent and effective policy in this sense in relation to abortion in particular?

A comprehensive, national sex education policy in school systems, but also in communities, the media, health institutions and other social actors is absolutely key. It is probably one of the most deficient fields that exist today regarding the subject of sexual and reproductive rights in Cuba. For this reason, it is necessary that the comprehensive strategy of sex education in the country be implemented in a broad and effective manner, that it effectively reaches all places, because an extremely serious problem in Cuba related to this has to do with teenage pregnancy.

While there are low birth rates in the country, there are also high fertility and birth rates in teenagers. And that is a serious problem. And those rates are even higher in rural areas, among teens of color. This has to do with difficulties and deficiencies in access to information on sexual and reproductive rights, on contraception methods, on the ways and procedures for the voluntary interruption of pregnancies, and above all, problems and great deficits related to comprehensive sex education, which have an incidence in this phenomenon.

What threats and risks do you consider exist today in Cuba for the right to voluntary abortion? What can be done against these threats?

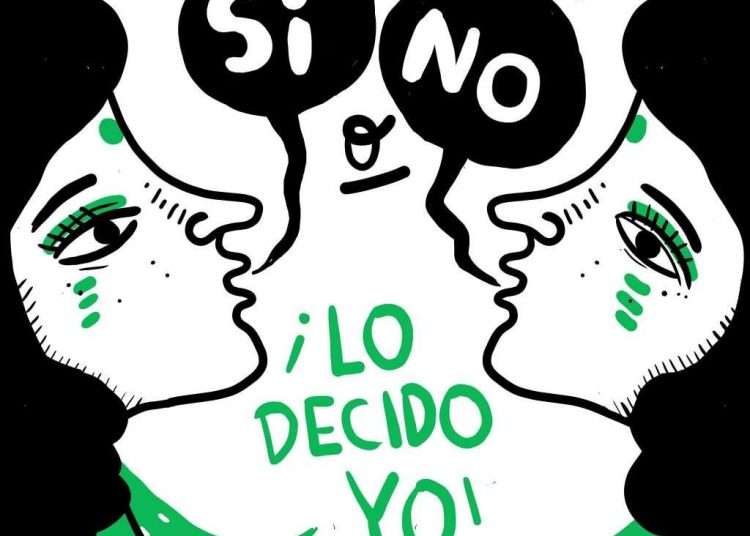

I think that the expansion of religious and non-religious conservatisms, which is something that became very clear with the discussion of same-sex marriage during the debates on the Constitution, and also with that and other issues in the recent debates on the Family Code, is an obvious threat, because, in addition, the issue of the voluntary interruption of pregnancies is part of this conservative agenda. And it is a mistake to think that it is only a religious movement; There is also a non-religious side, at least apparently, in an inexplicit way, in these tendencies. So, the advance of these conservatisms on the one hand and, on the other hand, the influence they are having in the Cuban regulatory and political field, makes them the most important threat, because, in effect, that influence can limit sexual and reproductive rights.

We have heard, for example, of religious groups that have accessed Cuban health centers, that have carried out their evangelizing work within health centers, that have tried to dissuade women from having voluntary interruption of pregnancies, that have influenced against the implementation of the sex education strategy, with which the impact and influence they are having, both in the institutional and non-institutional fields, is very evident. This is why, with all the more reason today, a conscious, deliberate and systematic action of the different social, state and non-state actors is necessary to ensure the exercise of rights, to intervene in social norms, in social dynamics, in the imaginaries of representation, in spaces of public communication, to, in effect, defend the sexual and reproductive rights of all people, and, in particular in the case of voluntary abortion, of women, of pregnant women. It is necessary to confront those conservative currents and those ways in which sexual and reproductive rights are being disputed, and specifically the voluntary interruption of pregnancies.

According to the Minister of Public Health, the Cuban authorities are working on a new Health Law in which the right to abortion is intended to be “shielded” in correspondence with the rights enshrined in the Constitution. What do you think about that? Do you think this proposal is enough or do you think that an issue like abortion should have its own independent law in Cuba?

The important thing is that abortion, as happens with other sexual and reproductive rights, is in law and is not a whim. The fact that a content is in law is something of the utmost importance, because the fact that it is so is a kind of shield against the risks and threats that it may have, in this case, against conservative and neoconservative influences, some that come from the religious field, but others that come from the non-religious field, which can dispute and, in fact, are doing so, as we have already seen, content related to sexual and reproductive rights, with comprehensive sex education and, specifically, with the voluntary interruption of pregnancies.

So, it doesn’t matter if abortion is in law or not. And the truth is that at the moment it is not, and it is important that it is. It is not enough that the Constitution speaks of sexual and reproductive rights. Specifically, we need the voluntary interruption of pregnancies to be not only regulated, institutionalized, included in regulations and medical protocols, but also to be in a law. And if there is not going to be a specific law on this subject, at least that it be in the next Public Health Law. If so, this would be a fundamental step to preserve this right.

Final version of Family Code published in Official Gazette of Cuba