She has just arrived in the United States after a more than 3,000-kilometer journey. Like other Cubans, to achieve this from Nicaragua she had to cross four borders and innumerable risks in these times of coronavirus, drug trafficking and cholera.

In Cuba she graduated in agricultural engineering, but life forced her to do various jobs, one of them founding a clothing store. Loquacious, outspoken and uninhibited, this 33-year-old woman decided to accept our request to retrace her three-week journey. “Nobody is prepared for an adventure of this kind,” she told me, among other reasons because of ignoring the dangers that lie on a path where insecurity, fear and uncertainty are three keywords.

From Camagüey to Las Trojes

I decided to leave Cuba because I couldn’t stand the hardships or the lack of a future for young people anymore. I went through Nicaragua. I did not risk buying the ticket in Cuba, but rather family and friends lent me the money in the United States and they bought it from there because in Cuba many times people are being scammed.

I left through the Camagüey airport, I saw families separating, crying, children with their mothers, sisters with brothers, you name it.

The flight to Managua was normal. Upon arrival at the airport, I established a cell phone connection with the coyote. He didn’t come looking for me, he sent someone else. From there they transferred me to what they call a safe house, but not before charging me $400 for the taxi from Managua to Jalapa, a Nicaraguan town not far from the border with Honduras.

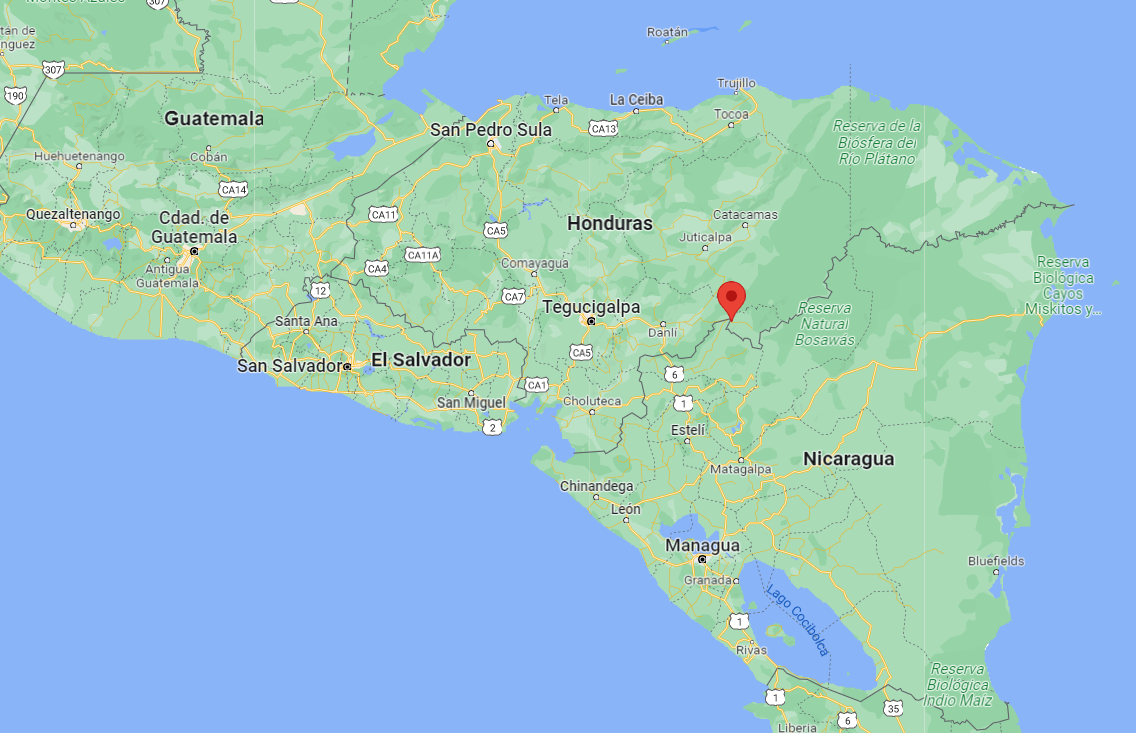

Right there they put us on a little motor vehicle to Las Trojes, Honduras. We got turned down at one point and one person charged us $80 just for telling us what we had to do. They sent us to the Immigration Office to request a safe-conduct, which costs 200 dollars. That was madness, there were people of all nationalities asking for papers, like 300 people a day.

Then there was a first ugly incident: at night we heard shooting, the Hondurans themselves told us that it was a confrontation between police and drug traffickers, a trauma for us because in Cuba we are not used to any of that. We were seven in total: six adults and a girl, the girl’s mother became very nervous, the father regretted having come and wanted to return to Cuba, until we were able convince him otherwise. It was like 40 minutes of shooting.

The next day we arrived in Tegucigalpa on a bus. Then we contacted Doctors Without Borders, who help you in many ways, from medical assistance to food and medicine. They themselves told us how to buy the ticket to get to the border with Guatemala. But on the way there was a second incident.

The police stopped us, we showed them the safe-conducts, but they told us that we had to pay them anyway for letting us continue. We told them that we were legal and that they couldn’t do that, but they, very sincerely, told us: “It’s true, we can’t arrest you or put you in jail, but we can hold you for three days and then you will lose the contact with your coyotes. You decide.” So we had to pay them 20 dollars for each of us. Then they let us continue. And from then on, the police continued to charge $20 per head at each of the checkpoints until we reached the border with Guatemala. All very well organized. Money speaks.

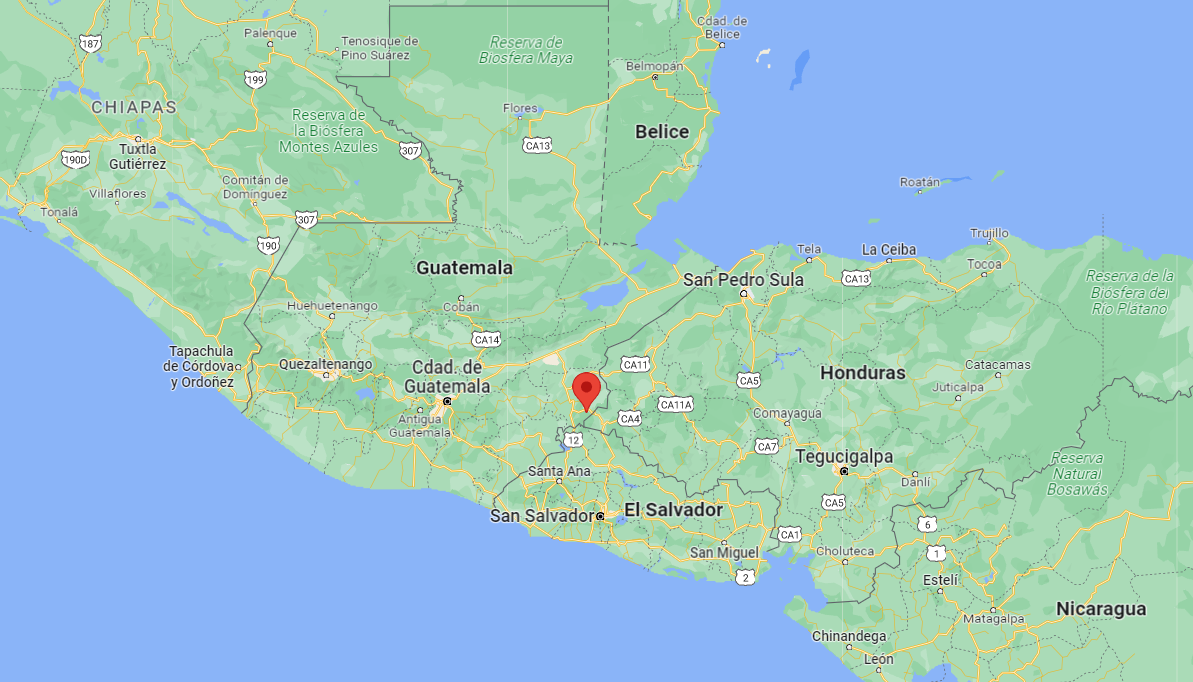

Entering Guatemala

Before reaching the border with Guatemala, the police told us: “you have to wait here until your coyotes come looking for you.” I contacted mine by cell phone. Then we got on a van that took us to a nearby point, not far from where we were. “Get off, Guatemala is over there and we cannot pass in front of them. We have to go around Migration.” “Going around Migration” meant to cross scrubland and climb hills. What impressed me the most was that when we arrived at the place of destination we were received by an elderly man, blind, who is the one in charge of the illegal crossing. He asked: “Who is passing by and how many are you?” We gave our coyote’s name and he let the seven of us through. But if you didn’t pay for that crossing before, that same blind old man reports you to the police.

Right there they put us on a Customs bus! until we reached a point where there was a taxi waiting to take us to a hotel in Esquipulas, a town in Guatemala. But to get there we had to go through three checkpoints. In the first, they asked us for documentation. The driver got out of the taxi, gave the police officer the name of the coyote and told him that we were six adults and one minor. That same police officer is then in charge of communicating to the other two that everything is in order. That’s why they didn’t stop us at the second or third checkpoint.

Then we arrived at the hotel in Esquipulas, everything was very well coordinated, there they provide all the services: food, laundry, etc. But we stayed two nights because, according to what they told us, there was a U.S. official in the area and until he left we couldn’t continue. There they told us that the Guatemalan police were all bought, that the head of the network met every week with the police chief and paid him to let us pass.

From Guatemala to Mexico

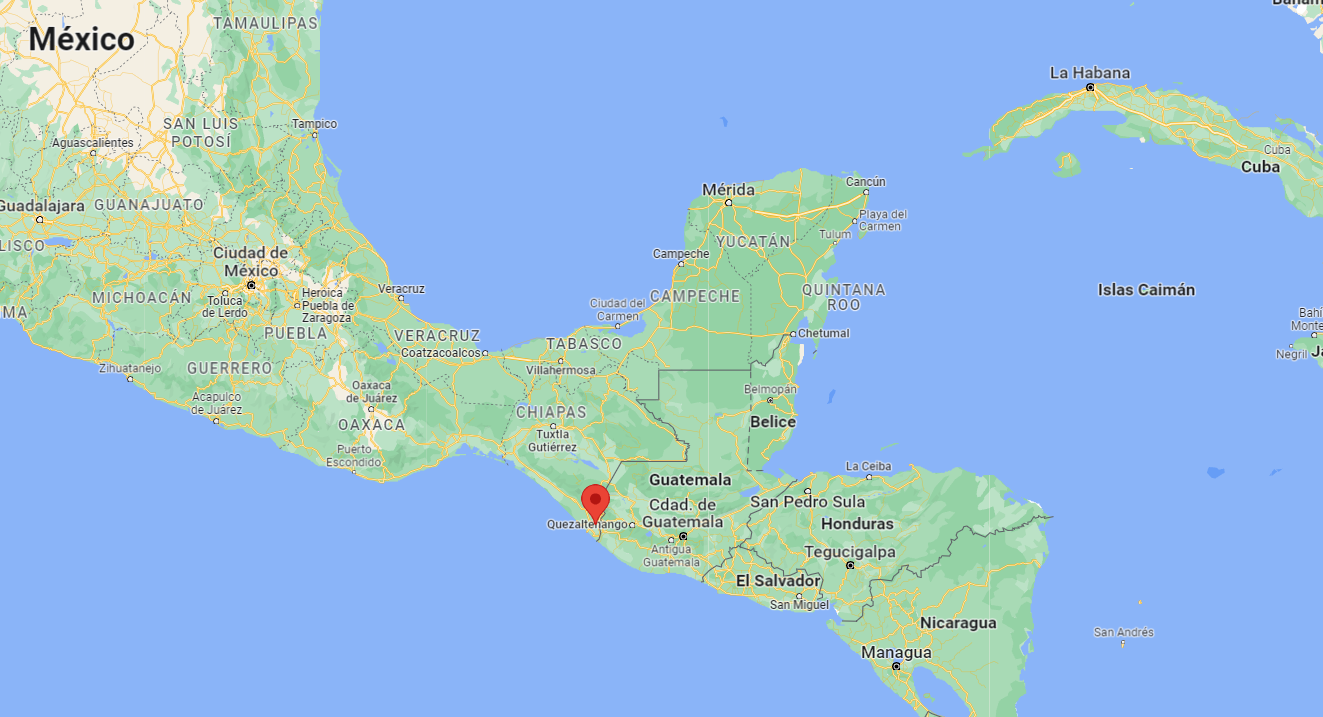

They cross you through all of Guatemala in small cars, you’re not crowded, you are comfortable. Only when arriving at the border with Tapachula, Mexico, did we have to go through scrubland. Everything else was by road. And let me tell you something: I didn’t feel unsafe in terms of rape and sexual harassment and things like that. But insecurity is something else. If the police catch you. If you can’t reach the end of your journey. All very tense.

On the Mexican side, three youngsters were waiting for us: two men and one woman, all three completely drugged. There we realized that we had to be calm, not even complain. They took us to a room in which we did not fit, we all stood there for about 2 or 3 hours until they took us out. They took us to a town, they put us on a bus that they pay for up to a point where you have to take a taxi. One pays for that, it was the first expense I had in Mexico. And then you contact the coyote who is going to take you to the United States.

Everything has to be paid in dollars. We were going to a house, 15 dollars per person. In Tapachula there were problems, every man for himself to catch a taxi. The law of the strongest. I had to get tough to get on one.

I arrived in Mexico without money, I had to be lent the 15 dollars to pay for that taxi. I had to negotiate with the coyote because they tell you that you don’t have to pay anything, but I didn’t even have money to buy a phone line to communicate with my family in Cuba. The fare for this journey is $2,000 from Tapachula to Mexico City and another $2,000 from Mexico City to the southern border, all the way to Piedras Negras. But you always have to have extra money for taxis or anything else you need.

They moved us to another house in the same Tapachula that had only walls and a roof. We had to sleep on the floor and without a mattress.

Traveling to Mexico City

The next day they put us in a small truck, it wasn’t big, 115 people, the mothers and children went first, but it was a journey on foot, 7 hours, all overcrowded, people fainted along the way, all men, I don’t know why we women didn’t faint. There were people from many countries there: Hondurans, Salvadorans, Cubans, Arabs….

Then we arrived at another house in a place called El Paredón and from there they took us to take a speedboat to San Francisco del Mar and made us cross scrubland because it was not safe to be on the riverbank. They took us to a hotel (they call anything a hotel), we were 17, we had to settle in two rooms with two beds each.

Well, when we got to a place we saw that there were eleven cars with undocumented migrants. They began to divide them by coyotes: those for coyote A, those for coyote B…and so on. We got into one. Then, at a certain point, you have to cross a river on a raft. In each one there is room for 15 people, in mine we were 21 but it was quite comfortable, I have no major complaints. The person who takes you on the raft is always in the water. You don’t get wet. They are those wooden rafts with truck tires underneath.

We left Juchitán de Zaragoza for Oaxaca. And in a place called San Dionisio the police discovered us. We were 15 Cubans in a van with the Mexican driver. They have a system they call “flags.” Each car is guarded by two others, one in front and one behind. The one in front checks to see if there are police, and if there are, he warns and one has to hide. From the police that isn’t bribed, of course.

The fact is that in that “flag” of ours, the drivers of the first car were drugged. The Navy, the most dangerous, because it doesn’t accept bribes, passed them by and they didn’t even see it. So the boss called them and told them: “Wait, I’m going to give you my radio.” When he was handing over the radio, a walkie-talkie, exactly at that moment the police came, they made a U-turn. The driver got into the vehicle like a madman and fled with all of us inside. For each illegal immigrant that they catch you carrying it’s a minimum of 12 years in prison. That was the worst experience of this trip. I swear there came a time when I wished the driver would stop and hand me over to the police.

A police car was chasing us. And we were saved because the driver made the decision to pass five cars on a curve. On one side, the road. On the other, a ravine. Horrible. Either dead or saved. The police did not dare do the same. And the maneuver gave a chance for the flag that was coming from behind to get ahead of the police car.

Then we went into scrubland. Everyone was nervous, tense, and then the driver told us: “calm down, you’re in drug-trafficking land, the police don’t come in here.” That’s really something! I said to myself. We were in a place called San Dionisio, from where the next day they moved us to a safe house in Puebla.

Already in Puebla, conditions began to improve. They placed us in a safe house, it belonged to a rich man, a rancher type. Our group was 17, but when we arrived at that ranch there was another group of 13 people there. About 10 minutes after arriving, the owner put a speaker in front of us. “If you want you can play Cuban music,” he told us. How wonderful! I said to myself, the first house I arrived at and they let me move freely, I don’t have to be locked in a room, I can go to the kitchen and even chat.

There were three Cubans who decided to leave the house, but when they were leaving, the owner caught them. There was a terrible ruckus. The Mexicans entered the house and told us that we would see how a lesson was given. They were a woman, an older man and a young man. They didn’t do anything to the woman, but she herself peed in her clothes and everything. The older gentleman was not beaten but was thrown down the stairs. They began kicking and punching the young man. When they decided to stop beating him, neither his face nor his eyes could be seen, all covered in blood.

The attacked did not tire of apologizing to the Mexicans. One of them said: “It’s the second time he’s done it to us, that coyote doesn’t want to pay for you and sends you out, but at first we thought you were escaping on your own.” After the three Cubans apologized; after we all promised that we were going to obey and pay absolute attention, it was as if a switch was pressed: “well, let’s put on music. Who wants beer?” said the Mexicans. They took a speaker, put on Cuban music at full blast. “Come down, come down, my husband is down there, he has food, sweets…. What do you want to buy?” I said to myself: “we are dealing with crazy people.”

A young woman and I decided to care for the Cuban. We closed the wounds on his face with butterfly stitches. When he came down the stairs he apologized to all Cubans for having put us at risk. And he started crying. He had left a six-year-old child in Cuba, and if he died and didn’t make it to the United States, his son’s future would be screwed. Then everyone started crying. I never saw him again.

The next day they took us to Mexico City, we arrived at a hotel, nobody was waiting for us, so we made the arrangements ourselves. There were no problems there. I went out, I went to the bank to withdraw money, to walk, and to buy food.

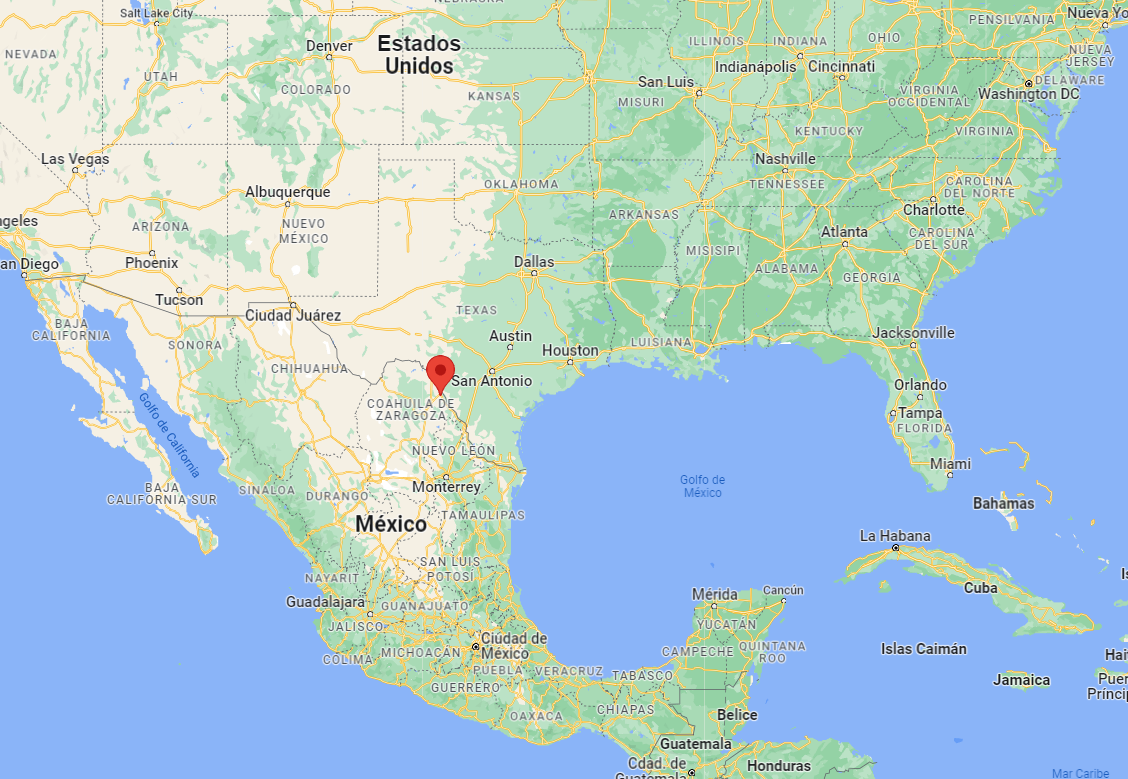

From Mexico City to Piedras Negras

From the hotel they then took us to a safe house. Starting from Mexico City, the owners of the business are Venezuelans. Our guides from there to the border were all Venezuelans.

The trip from Mexico City to Monterrey was about 13 hours. When leaving the Mexican capital, they told us: there are three routes: the first is the legal one, but it is with papers (I already said that we didn’t have them), the second the one drug traffickers take, and the third is the longest, the one that nobody wanted. To take the one used by drug traffickers, you had to ask for permission and at the time of leaving they had not been able to contact them, so we had to opt for the longest route. Who were the drivers of the cars? Police officers from Mexico City.… I decided to go with the oldest, he told me that he had 23 years of service in the police, that he had four women and had to support them, and that he also had to have an operation and that his salary as a police officer was not enough. And that he did “this” fort extra money.

They gave that driver money to bribe four checkpoints, but he was only charged at one (the others let us pass peacefully). So he said to me: “Look at this, a single checkpoint and they charged us all the money.” The Mexican was a big liar. We don’t know why, but the truth is that we went totally unnoticed at all those points, except for the one I already mentioned. Later we found out that the cars that were behind had been stopped. They passed, but they were delayed, you know why.

In Monterrey they left us at a mall. Other Venezuelans picked us up there and took us to a very good apartment, in a condominium, where they kept us for one night. We left the next day for Piedras Negras, where we were going to cross the river to the United States. They told us that two things could happen: go straight across the river or put us in a safe house.

But the first thing happened: straight to the river. They left us in a place where they promised us that the water was up to our waists or thighs, but that day they opened the floodgates and the water was up to our chests. But we were always able to walk. We had life jackets on, we were all tied up with rope so the pressure wouldn’t drag us along.

The three Mexican guides enter the water with you until you have passed a little more than half of the river. All the while, the authorities of both countries, Mexico and the United States, are watching you all the time. And when you get to the other side, they are already waiting for you….

***

* In the second part of this work, the witness recounts the detention process at the U.S. border and her entry into the United States. Some data has been changed to protect her identity.

Can this viewed on soanish language?