Cuba already has its own catalogue of art brut or outsider art, headed by Misleydis Castillo and Jorge Alberto Hernández Cadi, known as El Buzo.

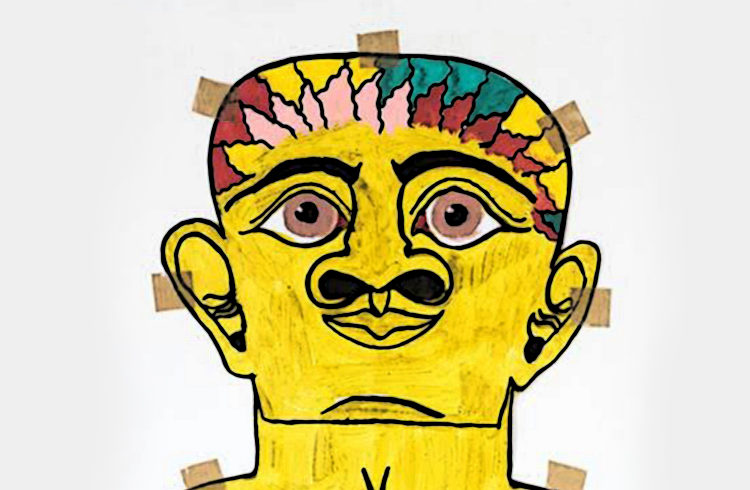

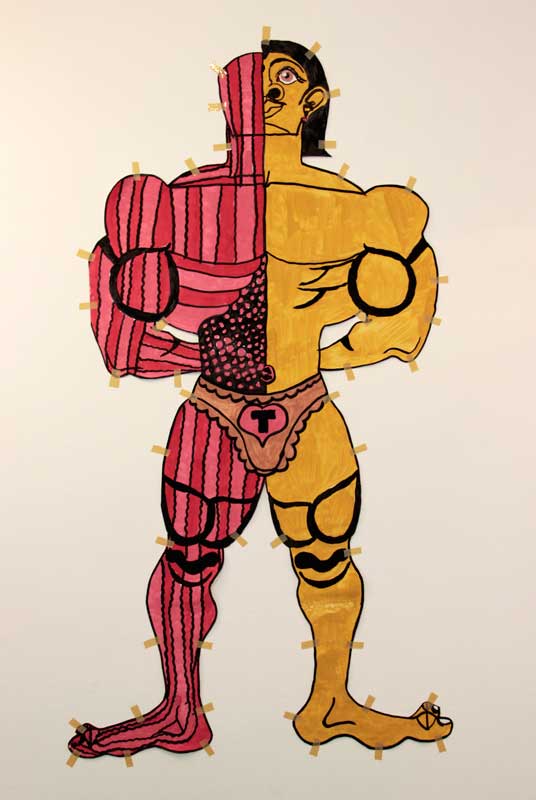

She, a deaf and mute and autistic, proposes pictorial images of strong men, body builders, with a repetitive effort of achieved minimalism. He, bipolar and a schizophrenic, has the habit of collecting pieces from waste material to then recycle them and turn them into art, once they adopt diabolic features.

Both artists are exhibiting their works in the Spanish Embassy in Havana together with Spaniard Ramón Losa and U.S. Milton Schwartz thanks to New York professor and art critic Lyle Rexer, curator Daniel Klein and Juan Martín, coordinator and executive director of the National Art Exhibitions by the Mentally Ill Inc. (Naemi).

However, this is not the first exhibition of the brut artists on the island. “Works by Misleydis have been on display in galleries in France and the United States, and have been sold at high prices because they are well-liked,” said the also poet Juan Martín, a Cuban established in Miami, in an interview with OnCuba.

Why the union of these four artists of different nationalists in the Encuentros /Encounter exhibition?

Everything comes from art brut, conceived by French artist Jean Dubuffet to describe art created outside the official culture by psychiatric hospital patients. Nowadays, the concept extends to self-taught or naïf artists, even when they have not been hospitalized in mental health centers.

On the other hand, the union of these artists in the Encounters exhibition responds more to the differences between them and that we have had that foundation in the United States for 29 years and have been going to many countries in Latin America, and others like Great Britain, in search of handicapped persons with artistic talent.

Our aim has been to contribute to their realization as artists, because they produce something useful for society. We represent the sphere of the outsiders so they can exhibit, despite the fact that in the beginning their aim was not to make art.

Misleydis’ work is increasingly closer to refinement; there is a technical and stylistic improvement. What I most like about this is that none of them can be told to paint a portrait or to make a work because it is being sold in New York for 100,000 dollars or that they represent several strong men in such and such a way, since Misleydis does it spontaneously, as she wants, and not because of the mercantile logic that generally involves artists.

How has the introduction into the market of this type of art been?

I have had proposals from French galleries and also in Miami. It hasn’t been difficult to insert it into the market because this generated a great deal of interest, because of the very line of work that characterizes the foundation and that type of art in general. The works are sold very well; some have even been sold for thousands of dollars.

In all this there’s a key question, since many Cuban followers of the Brazilian O’Globo soap operas surely still have a close memory of the character who suffered from schizophrenia and, at the same time, was capable of painting the world’s most perturbing portraits, without receiving in exchange a minimum of compensation.

How are these artists economically remunerated?

They are paid what the person who cares for them decides. In Misleydis’ case it’s her mother, and I can say that she has been living rather well since her works started being marketed, being exhibited and being sold in international circuits.

Misleydis’ mother confirms this: “We now have a better quality of life. This has no explanation, it’s a miracle because she never went to an art school, we never taught her to paint and, however, her art is very beautiful. The first thing she did was a landscape that today we have hanging on one of the house’s walls, and she also does bigger format paintings.”

Why have you chosen Havana as the scenario for this collective exhibition by artists of three nationalities (Cuban, Spanish and U.S.)?

In the first place, because I’m Cuban. I always had that dream and the idea was to bring originals by several U.S. artists. But it was very difficult to transport them and we weren’t able to do it. We will do it at another time and we hope that the Cuban cultural institutions will open the doors because it would be good to bring those U.S. artists to the island.

***

But it was not only Martín. Professor Lyleir Rexer, of New York University, also hopes to bring U.S. artists to the island and carry out exchanges. He wants to build bridges and that his projects are able to be exhibited in the building of the Museum of Fine Arts.

He makes an effort to speak in Spanish to express his assessments about the art that comes and goes through the Gulf currents, and in whose waters the northerners and Antilleans converge.

“There are self-taught artists in Cuba and the United States. I would like to bring them closer, above all those from the south of the United States, with whom Cuba shares history. This is a good subject to connect the two countries, although it isn’t exactly through folklore,” he says.

“Internationally there are tendencies that are in charge of conceiving art in a more holistic way, without real borders or genres.”