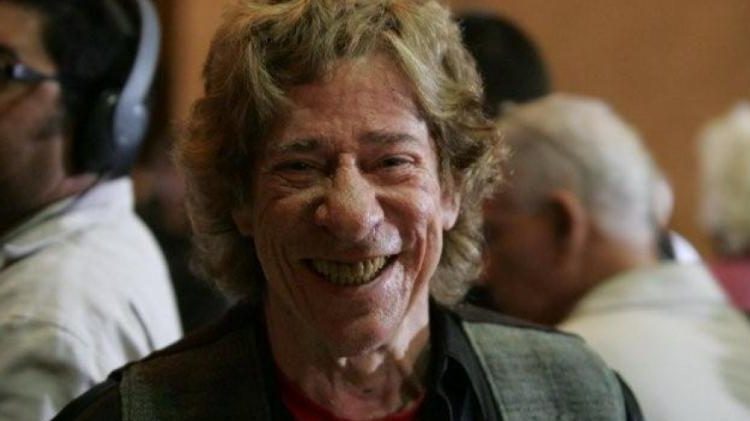

Some might think that he’s a classic from another era, another time, but in each of his words, in each dialogue, rests the identity and life of this country. If we make a brief review of his work, we can recognize that he was totally current in Cuban events. The island mourned his death one July five years ago, at the age of 82, and he is still missed on national stages today.

Carlos Ruiz de la Tejera was not only that actor who took Cuban humor to its best summit, but also a man who designed his life based on the pleasure he undoubtedly felt when launching those vernacular pieces for the public and getting back the barrage of laughter and phrases of admiration that he collected for decades on Cuban stages.

Anyone who has seen him on stage can remember the fervor with which he established one of the greatest bonds in memory between a comedian and viewers in a performance. His face and his movements on stage were an ode to excess. He was able to interpret with his features the lines he declaimed and the audience couldn’t take their eyes off him throughout his show.

The mastery with which he wove his shows could not come from any other place than from fatigue and pain, from the monastic discipline with which he rehearsed his monologues and dialogues until he found the level of perfection that later overflowed in the nights of Havana theaters.

His technique was seasoned in the most brilliant traditions of Cuban theater. He began to refine it since he joined, during the 1960s, the National Dramatic Ensemble together with the notable Miguel Navarro, Herminia Sánchez, Adolfo Llauradó, Asenneh Rodríguez, Alicia Bustamante and José Antonio Rodríguez. His made his debut with this influential group with the work of Nicolás Dorr La esquina de los concejales. The demonstration of his talent was so deeply rooted that the playwright himself thanked him for having defended the piece.

Carlos was a mirror of precision. He had a recognizable charisma to understand what the public needed at all times and he interspersed his jokes to cause the greatest dramatic effect.

I had many conversations with this chameleonic and tremendous actor. The first occurred at the end of a play at the Mella Theater in Havana. There, behind the scenes, he told me a little about his perception of Cuban humor and the rigors of his work before showing the final result on stage. His words confirmed that he was not satisfied until he saw he had reached his highest level of perfection and that he had truly achieved that his world fully inhabited his works.

His performances were a portrait of Cuban society and the vision he had about his country. He never resorted to the easy joke, to the simplicity of speech born of the pun or shameful mockery. I remember that when I wrote his obituary for Granma newspaper, I said something like he was a man who raised humor to the dimensions of science. Over the years, I think that is one of the attributes that has led him to live on and overcome the harsh tests of time. However, I believe that the lack of memory that increasingly haunts like a ghost the Cuban media and some institutions, has overlooked the magnitude of his work and he is hardly mentioned in these dark times.

After that night in which he revealed some keys to his professional immersion, I greeted him again during a phone call he made to the newspaper’s culture department to announce the gathering he led and loved as a spoiled child. “Michel, can you publish for me the next date of my gathering? I have several guests, among them, as you know, will be Jesús del Valle (Tatica).”

The calls became habitual. The phone almost always rang on my nights on duty, and his requests never ceased to amaze me by the level of humility he showed when he explored the possibility of his meeting with his audience being announced in the newspaper.

I recognize that at times it was not easy for me, because I was writing some closing information or reviewing some last minute material. He asked me to take the data over the phone because he could not, for some unknown reason, send it to me by email. I felt I had to do it, even if I was at the delivery stage of a news piece. Always, in return, he invited me to his gathering at the Napoleonic Museum. When I finally dropped by the installation, I discovered that it did not need promotion in any medium. His audience overflowed the room, in an incredible communion.

Coincidentally, my debut in his gathering coincided with the impossibility of publishing his announcement because that week the cultural page was absent due to more relevant editorial issues, something that, incidentally, did not stop annoying the journalists who wrote for it.

You can’t talk about Carlos Ruiz de La Tejera without mentioning his passage through cinema. In that discipline, as in real life and on stage, it was impossible to go unnoticed. He defended characters in front-line films such as Los sobrevivientes, The Death of a Bureaucrat and Las doce sillas by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea. Many remember his foray into the seventh art, another of the concerns in his incessant professional searches.

In recent years, I have entered a frontal war with my memory, which sometimes becomes, for no apparent reason, a labyrinth with no way out. It has played tricks on me by erasing dates, names, phrases, books, faces and concerts that, for the value they contain, should never have left the corridors of my mind. That has caused me to have to apply myself thoroughly to confirm topics that are very close to me and about which I have written ages ago. In that memorable effort that I make when I remember, I see as a fading portrait our great humorist, making his emblematic jokes about the shopping bags or the camel, among many others.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h-qln8rg7Po

I recognize that at some point my memory could be completely erased, but what should never be erased definitively is the entire memory, without misrepresentations, of a country.