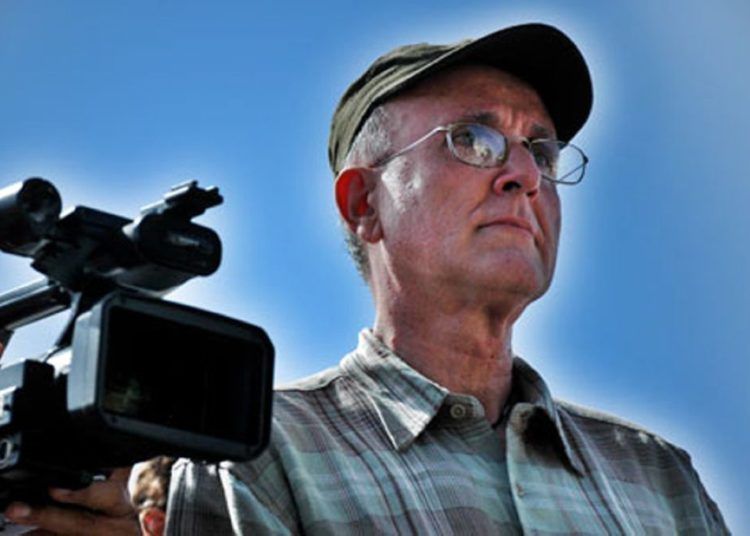

Tomas Piard was a filmmaker who made no concessions. He got behind the cameras as if it were a method to survive and a way to bring to the limit what can be understood as freedom of expression in the cinematographic sphere.

Influenced by the aesthetics of surrealism, Piard belonged to that class of filmmakers who could be considered a maker of “cult” movies. His work was especially for those who face cinema to try to decipher the most hidden mysteries of life and enjoy the harshness and spiritual conflicts that this process can entail, that exchange between the filmmaker and the spectators, between his way of interpreting the most hermetic aspects of life and reality.

Piard was a filmmaker who lived according to his own rules, with his own time and based on that he exercised a profession he began in the 1970s and which he assumed, as we said, as a profession of faith. He was witness to the most tremendous and complex eras of Cuban cinema and from his uniqueness he knew how to find the formulas to direct films that helped expand the conceptual themes and artistic horizons of national cinema.

In his creative record we see a filmmaker who could never part with his influences. El viajero inmóvil, one of his last films, is an extremely faithful proof of that. That Lezamian spirit that always accompanied the look with which he observed reality was fully evident in this film in which he recalls the author of Paradiso based on a very personal conception.

The film, with a theatrical atmosphere full of allegories, hidden personal allusions and existential metaphors ̶ like much of Piard’s cinema ̶ was not made for easy comprehension, nor for normal criticism.

El viajero inmóvil was simply the filmmaker’s tribute to Lezama’s centenary and perhaps also the total revelation of all that intricate aesthetics that defined his cinema for decades.

This film, like no other in his filmography, was a visual shot that struck the snake of controversy.

There were many who criticized it, who called it a minor work, who claimed that the filmmaker had lost himself in a labyrinth where he lost the way out, while others felt as theirs that tribute to Lezama and no applause was kept for this filmmaker who assumed each film as if he were trying to write Paradiso.

And you know the pain that that iron discipline can cause to the spirit.

Born in Havana, Piard was a universal Cuban. A kind of renaissance man for national cinema. He also ventured into theater (Si vas a comer, espera por Virgilio), television, he entered the world of museology, Asian art and psychology.

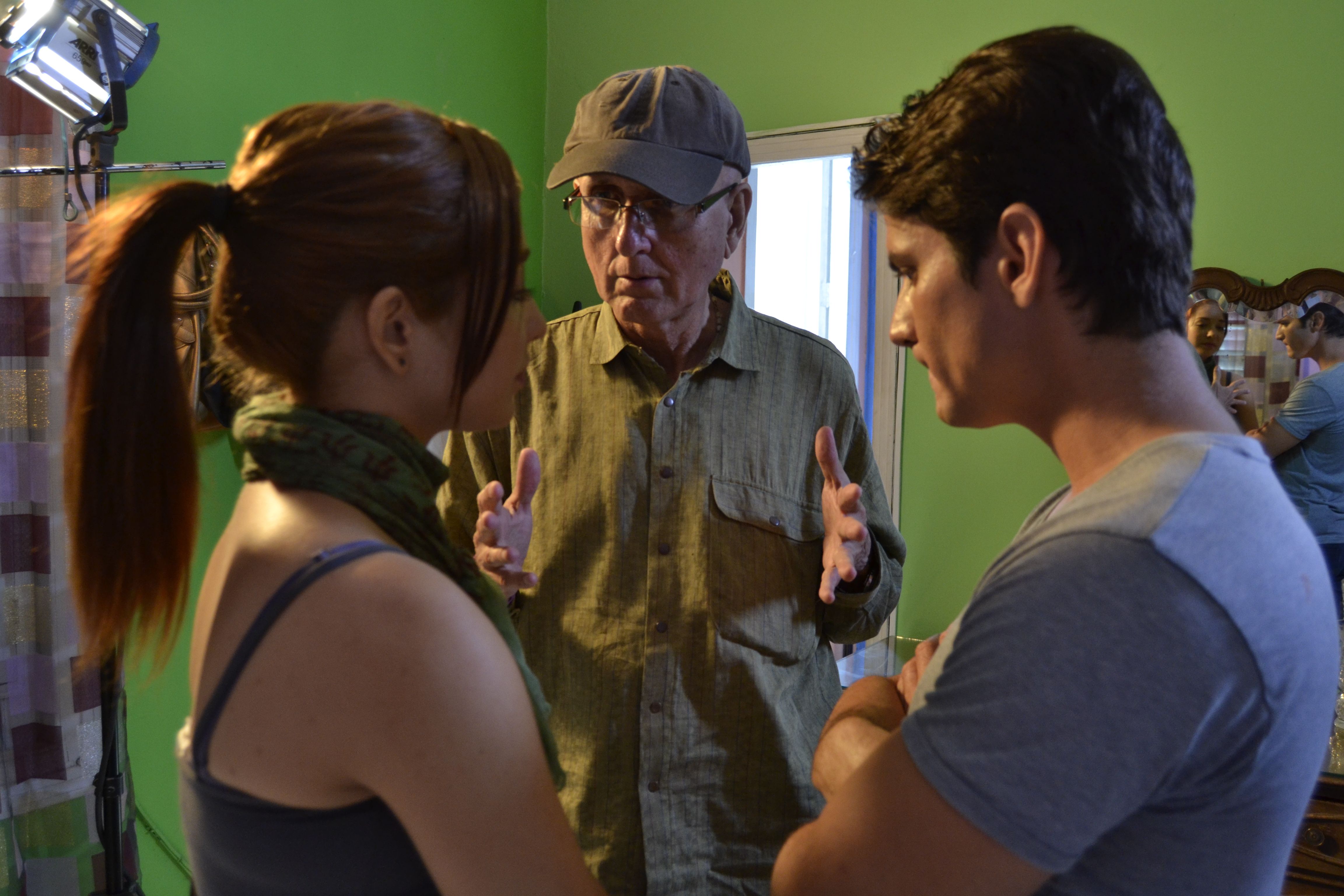

With one of the broadest cinematography of Cuban cinema, he was the discoverer of several actors who would later make time. He filmed Ecos, the first fiction feature film in Cuba directed in an amateur manner and starring a young Cesar Évora; then he directed Boceto in which he gave the opportunity to Jorge Perrugoría, who later reached stardom in Strawberry and Chocolate with Vladimir Cruz.

His filmography includes titles such as Ítaca, Trocadero,162, bajos, Los desastres de la Guerra and La ciudad, his last film.

In January 2015 he answered OnCuba about his film.

Why did you choose the title La ciudad to talk about emigration in this feature film?

La ciudad is the summary of our Island that is currently in the process of transformation. The film is about today, it is very current and also deals with the process of restoration of the Cuban spirit. Cubans’ humanity has deteriorated, although it hurts to say it; I feel that they have been denigrated psychologically and in many other aspects, because the material part has had a very negative impact on human beings, their values and their spirituality.

Emigration has been a phenomenon that has touched many Cubans and has been addressed in our media on several occasions. What innovative aspects do you propose with this film?

I speak of the problem with religion. How hard it was for Catholics to live in Cuba a few years ago. Believing in Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre was a crime, that was the reason why a girl was expelled from the university and now pilgrimages are made to her sanctuary and they walk her around the country as the patron saint of Cuba that she has always been. The first story is about women, I touch very intimate problems like this referring to faith and what was renounced to defend religious beliefs at that time. For years, when you didn’t live, we who are much older lived things that today do not happen. We had to face many terrible facts that today it seems they would want to erase in a stroke. In junior and senior high, and university, those who thought differently were discriminated against, those who had another ideology and religious beliefs were expelled from educational centers and in the end you had no choice but to leave the country. There is not a single Cuban family that is complete, they all lack a member who emigrated, all are unfortunately fractured. To give you my example, very recently I reencountered some very dear cousins of mine who emigrated during my childhood and I never heard of them again. They were in their twenties when they left and now I can communicate again with one of them who is already 80 years old. The dialogue between us cannot be normal because all those years of absence and silence weigh. The film is about that. It also deals with the idea of leaving Cuba that accompanies the new generations. Many young people are thinking about how to emigrate, they graduate and they leave. I have lived this as a professor at the Faculty of Audiovisual Media (FAMCA). Another interesting aspect that the film presents is the impossibility of loving due to distance, to the loves that have no future and that are truncated due to emigration.