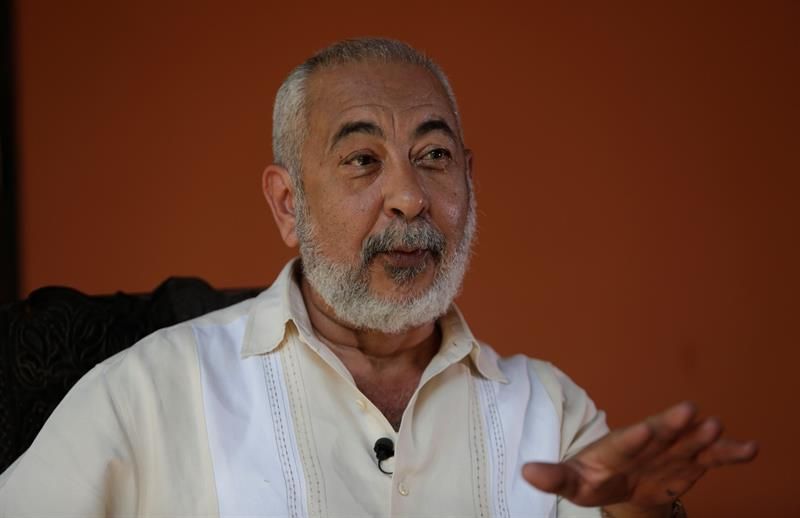

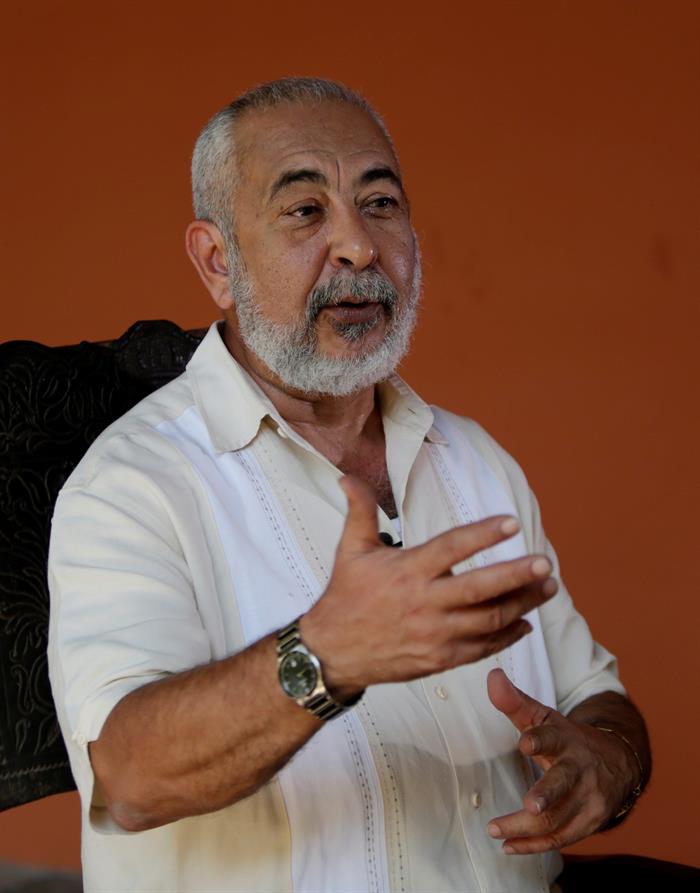

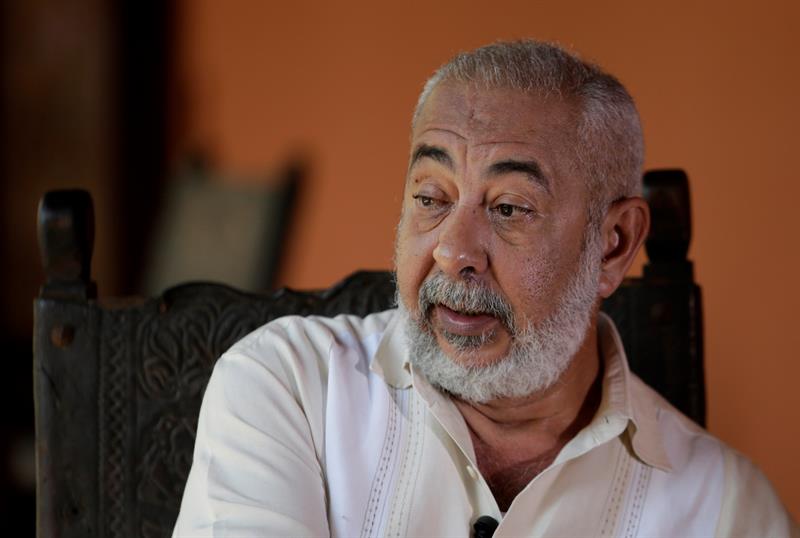

The detective genre “is a very generous fiction that allows the writer to tell everything he wants,” says Cuban writer Leonardo Padura, considered one of the masters of the genre.

Crime fiction has always had the majority preference of the reading public. However, literary criticism and the academy had been evasive about it until 25 years ago things started changing, this journalist, scriptwriter and writer born in Havana in 1955, who recently participated in the Cartagena de Indias Hay Festival, says in an interview with EFE.

“Now it has entered the mainstream of literature and is no longer considered a subgenre,” says Padura, a fervent admirer of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Antonio Muñoz Molina and Eduardo Mendoza.

Last year, the Cuban master of the detective novel received the Barcino Historic Novel International Prize. The jury highlighted the contribution of detective Mario Conde, his inseparable fiction partner for 28 years, to understand contemporary Cuba.

That a contemporary protagonist of fiction stories has become a historical reference “is one of the best compliments I have been paid,” Padura confesses.

In La Transparencia del tiempo (2018), the character of Mario Conde begins to take stock. “He has eaten little and badly, he has smoked a lot, has drunk too much and begins showing signs of fatigue, not only physical but also historical, mental.”

“It’s an agonizing novel in a certain sense, not only because of the character’s age, but because of the aging of the situation, which is reaching a point where it will necessarily change,” he says.

The novel ends on December 17, 2014, precisely on the day it is announced that Cuba and the United States are going to start talks to reestablish diplomatic relations.

“Unfortunately, afterwards the events reversed that moment in which we had the great hope that many things could change,” he says.

Padura started working for cultural magazines at the end of the 1970s, at the same time as he was writing his first stories. “At that time, you finished a book, you handed it over to the publisher and four years would go by before it was published.”

Although he never knew about the inverted pyramid of information, he revolutionized the way of doing journalism in Cuba with his works for the magazine El Caimán Barbudo.

“Fortunately I was able to write what I wanted, as I wanted and as much as I wanted, something that is unusual anywhere in the world, and in Cuba, much more.”

But the authorities considered he was anti-establishment and sent him to work in the daily Juventud Rebelde to be re-educated. There he began writing feature articles in the style of Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe. Today, with the digital speed, it would have been much more difficult.

“The number of processes that are being shaped, transformed and even disappearing are many. We are in one of the most obscure situations journalism has had,” he reflects.

Padura has just published a work in the Spanish edition of The New York Times about the post-Revolution Cuban exile. In the last version he had to cut the text by removing adjectives. “I don’t get it. That kind of journalism is very difficult to do,” he laments.

Tolerated by the regime in Cuba, where he usually resides, Padura is silenced or ignored, despite having received such important recognitions as the Princess of Asturias Award, the honorary doctorate from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) or, more recently, the Barcino Historic Novel International Prize.

“It’s an absurd situation. I walk through Cartagena or Medellín and people approach me because they know me. However, in Cuba, someone decided that this visibility of mine was not good. It shouldn’t be so difficult for Cubans, who are my natural public, to not have the right to read my books. That hurts,” he regrets.

Padura has doubts about the continuity of his country’s political system as it is currently conceived. “One will have to see how it is sustained, because wages are not enough to live on, and that’s not what I say, Raúl Castro has been saying it for almost 10 years.”

“Modifications have to be made, because if they try to resolve the same problems with the same methods that have not worked, we will have the same problems again.”

When he studied Latin American Literature at the University of Havana, Padura studied two careers, one academic, and the other, that of reading all the books he hadn’t because he had spent all his youth playing baseball.

His love for the “king of sports” is still alive. Padura went to collect the Princess of Asturias Award with a baseball in his hand and professes that he could have become a good technical director.

“Perhaps I don’t know much about literature, but about baseball, I know it all.”

It’s going to be finish of mine day, however before ending

I am reading this impressive post to increase my knowledge.