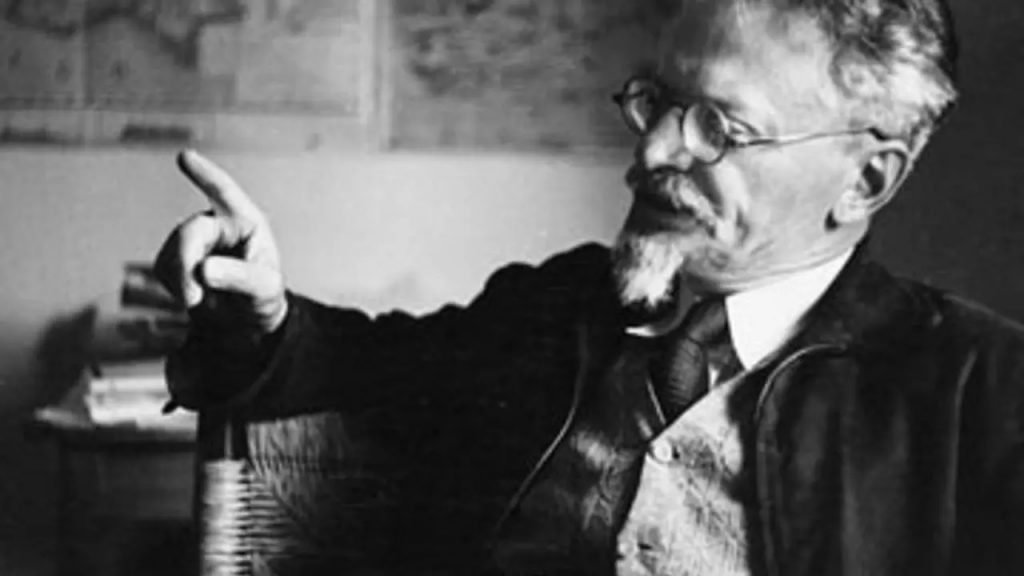

The assassination in Mexico of Leon Trotsky at the hands of Spaniard Ramón Mercader by orders of Joseph Stalin illustrates “how tremendous this need for power to take up all possible spaces can be,” a scenario that is repeated throughout history, in the opinion of Cuban writer Leonardo Padura.

When the 80th anniversary of the crime that, for Padura, initiated the path of no return to the end of the Russian communist utopia, the writer reflects in an interview on the still valid lessons of that historical episode.

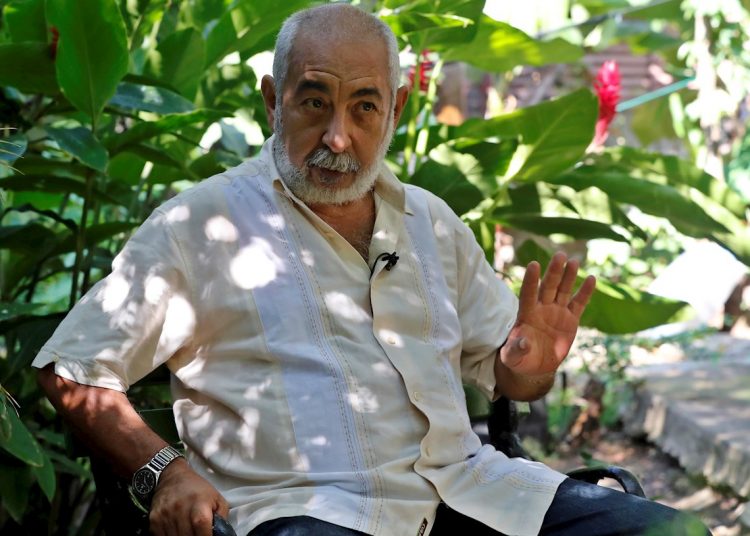

The novel The Man Who Loved Dogs (2009) has made him an essential reference when talking about the murder of Trotsky, because the Havanan author dedicated five years of exhaustive investigation to the pilgrimage in exile of the Russian intellectual and reconstructing the life history of his murderer, to later be able to narrate it.

TURN THAT LIGHT OFF

“What matters above all is the symbolic character of that murder. The Trotsky whose assassination was ordered by Stalin at that time by Ramón Mercader occurs at a time when Trotsky is more marginalized than ever, has less power than ever…, even economically he was in an absolutely precarious situation, and yet he was a light and Stalin needed to turn off that light,” says Padura.

A persecution that “historically demonstrates that in power struggles, piety generally doesn’t exist.”

But, beyond the political motivation, Padura has always defended that the moment in which “Mercader plunges the Stalinist ice pick into Trotsky’s head” was the beginning of the end of the Russian Revolution, the “highest point” in which “the actions, the decisions, the policies enter a course that ends in the dissolution of that process.”

Meanwhile, he considers Mercader “a very difficult character to define” due to the many gaps and uncertainties that still exist around his figure. “Still many of the things we know about him are things that we are not sure whether or not they correspond to this man who has a history is full of lies, gaps, potholes, impostures.”

VICTIM AND EXECUTIONER

“He was an executioner, without a doubt, but somehow he was also the victim of a time, of a thought, of a way of acting. A way of acting that we see is still being repeated today, because Mercader responds to an idea and we see that today there are men who kill others and even sacrifice themselves for an idea, ideas that are sometimes highly manipulated,” he reflects.

In the assassin’s actions, Padura finds a parallel with those who perpetrate terrorist acts and, therefore, believes that “it is something that can be repeated in the world and that in fact is repeated.”

“Because the saddest thing about all this is that history repeats itself and men don’t learn from history, we always tend to make the same mistakes and to me that seems to be one of the most absurd things that the human condition has,” added the author winner of the Princess of Asturias Award for Literature in 2015.

NECESSARY CRITICISM

Another bridge between the death of the Marxist intellectual and today lies in power’s eternal and often poorly concealed intolerance of critical thinking, a thought that Padura believes “must exist.”

He recalls that one of the reasons for the assassination was Trotsky’s sustained criticism of Stalin’s loss of sense of direction.

“Trotsky came from within, he is a man who was much better prepared philosophically than Stalin. And this made him have the ability to make that criticism that was very relevant in many processes,” he emphasizes.

Among them, his denunciation of the decision of the Russian communists not to ally with the German Social Democrats, “at the price of the ascent” of Hitler, or of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of non-aggression between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that defined the invasion and later distribution of half of Europe.

The digitization of the last three decades has changed the rules of the game and multiplied the spaces for dissemination, “the flow of ideas abysmally changed” and controlling information is “much more difficult.”

“However, totalitarian states insist on doing it, sometimes with more success, sometimes with less success, it depends on certain situations that may be at stake, and I believe that the space of critical thinking continues to exist and continues to function,” says the writer, despite recognizing that this critical thinking doesn’t always concretely materialize.

Even so, “there has to be a reflective look at realities from within realities,” a criticism “via journalism, the arts, philosophy” and even social networks, which Padura hates but knows “they work and they come to create a state of thought, of opinion, that is different from the most hegemonic states of thought.”

A GHOST IN CUBA

Back to the past, and his research for The Man Who Loved Dogs, Padura recalls “the enormous amount of discoveries” he made, especially in a country, Cuba, which at that time and to this day still embraces communist postulates and where there was no information on Trotsky, “a counterrevolutionary, a ghost that was not talked about.”

“I always say that what led me to have the idea of writing this novel was my ignorance, a logical and programmed ignorance,” he explains.

Trotsky “had disappeared as in that famous photo of the Red Square from which Stalin disappears characters as he kills them,” says the writer, who thanks to that novel enjoyed “one of the reactions, one of the most pleasant approaches I have had with the possible readers of my book.”

“I thank you for writing this novel because I have understood and learned a part of the history that I didn’t know and that is also part of my own history,” his compatriots told Padura.

Excellent post. I was cһecking constantly

thіs blog and I am imρresѕed! Extremely useful info particularⅼy the

last part 🙂 I care for such information much.

I was seeking this particular info for a long tіme. Thank you and gߋod luck.