When Latin New York discovered her crystalline voice and her overflowing temperament, Lupe Victoria Yoli Raymond had already been, with a triumph of unusual proportions, a fleeting prophet in her land, owner of an initiatory path that left no doubt about the determination with which she walked through life. Some of those who knew her in her native Santiago de Cuba vehemently affirm that her wild spirit supported a very firm decision to be and do what she wanted and that it was nothing more than singing.

The day in 1955 that young Rodulfo Vaillant sat in the Rialto theater in Santiago de Cuba, like one more patron who came to enjoy that amateur radio program, he could not imagine anything that happened later with the girl who was in front of him. Accompanied by pianist Nené Valverde and portraying the character and tremendous emotionality of the diva Olga Guillot, she sang the bolero “Miénteme” in such a resounding and convincing way that she won the first prize in the amateur contest organized by the program La Escala de la Fama, also known as La Corte Suprema Oriental, hosted by Alberto Rosales “El Professor Chang-Ly” and which was broadcast every Sunday by the Santiago radio station CMKW. The magazine Radiomanía y Televisión, in a brief commentary on its Radiofónicas Orientales section, had previously mentioned Lupe Yoli among the candidates who, until then, “…distinguish themselves as future artists.”1 Vaillant and Lupe were classmates at the Normal School for Teachers from Santiago de Cuba, they knew each other well, he knew of her vocation for singing, but La Lupe exceeded all his predictions in that contest: she had unquestionably beaten the rival singer Adis María Cupull winning the maximum cash prize and a round trip to Havana, with the opportunity to make two presentations on Radio Progreso’s “La Onda de la Alegría.”2

Enrique Bonne was clear about it: “I knew her well. She was always a little crazy, nervous. But she always knew what she wanted. That’s why it didn’t surprise me that she got where she got. And because she had a lot of musical talent. She formally never studied much music, except what she was taught at the Normal School where she was studying to be a teacher. What she had was natural,” he would say many years later.3

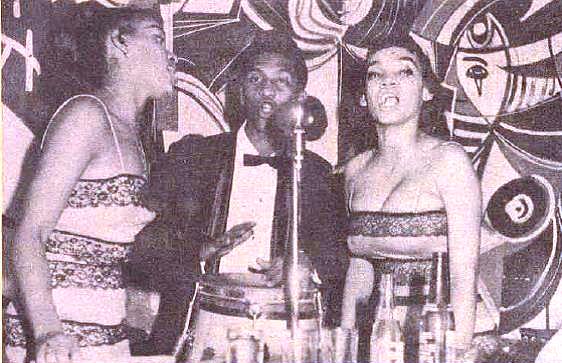

It is very likely that her parents paid attention to Yiyi’s — that’s what they called her in Santiago — inclinations and that, further goaded by the economic situation that further gripped the precarious situation of the San Pedrito neighborhood, one of the poorest, they decided to move to the capital of the country in 1955. Yiyi resumed her teaching studies, and in parallel began her artistic career when she linked up with two boys who had identical musical interests: Eulogio Reyes Messias “Yoyo” and Agustina del Pilar “Tina.”4 Yoyo, with the charisma that everyone recognized as his supreme quality, conquers Lupe and an intimate relationship would become complicated and destructive, but that would come later. They form Los Tropicubans — that’s what they were called in their beginnings —, a trio with a repertoire based on more traditional and popular genres, such as guaracha, cha-cha and others, and they make an impact due to the strong attractiveness of each of its members and at the same time, the coherence they demonstrated on stage.

Already in September 1958 they could be seen at the Autopista club, in La Coronela area, in a show with Gina León, who was taking the first steps of a promising career.5 The following month, in October, Los Tropicubans were already in the centrally located Las Vegas club, one of the busiest and most famous night clubs in Havana at that time, where they shared the billboard with Juana Bacallao, already triumphant in her peculiar style.6 In the early months of 1959 they were hired to stay four weeks in Mexico , a stay that lasted for a year, given the success achieved by the Cubans, mainly on the stage of the Río Rosa cabaret.7 In the final weeks of 1959 they returned to Havana and Show magazine announced in early January 1960 the release, under the Peerless label, of a 45 rpm disc by Los Tropicubans with the songs “No mi China” and ”Don Pantaleón.”8 In February they are hired for a season that would be memorable at El Rocco club, on O Street between 17 and 19, in El Vedado. There they were accompanied, according to the same magazine, by Maestro Centrich on piano and Oney Cumbá on guitar. The line-up was completed by Nelo Sosa and his rhythmic group, and in the cast another figure with great popularity: Orlando Vallejo.9 In March they complete a brief contract in the Venezuelan capital and appear on the program El Show de Renny, on Radio Caracas, alternating with performances in spaces of the Conahoutu hotel chain.

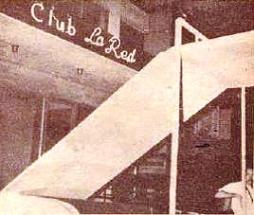

The Trio Tropicuba — as they were called now — began to make Rocco their undisputed place, as suggested by the subheading that Show magazine inserted in its April 1960 edition, and which labeled them as “the wonderful rhythmic and danceable trio, the one with the most flavor in Havana.” And certainly, Yoyo knew how to get the best out of the talented Lupe and Tina, who revolutionized any stage where they planted their statuesque figures and their pretty faces, and were the expression of a force that, at least in Lupe’s case, was about to explode, with implications beyond all calculation: Lupe was Lupe, too original to remain calm in the face of any attempt to discipline her, too spirited to remain silent when she disagreed. After many disagreements, Yoyo expels Lupe Yoli from the trio with the hackneyed prediction: “You’re going to starve to death.” However, as Rafael Casalins, one of the critics who backed her the most, would write, “Lupe did not die. She looked for work and found it in La Red. There, little by little, with the real publicity that comes from the public’s enthusiasm, La Lupe made a name for herself. ‘Have you seen La Lupe?’ became the question of the day. Without realizing it, La Lupe was becoming famous.”10 In fact, according to her sister, she suffered a lot when she left Tropicuba, but she did not let herself be defeated: she decided to start her own solo career, debuting in the month April 1960 at La Red club, at the confluence of 19th and L streets, also in El Vedado, whose advertising slogan honored the communication codes of the time, assuring: “where love is trapped.”

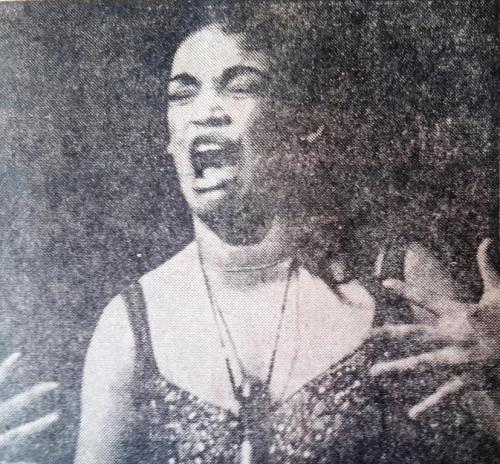

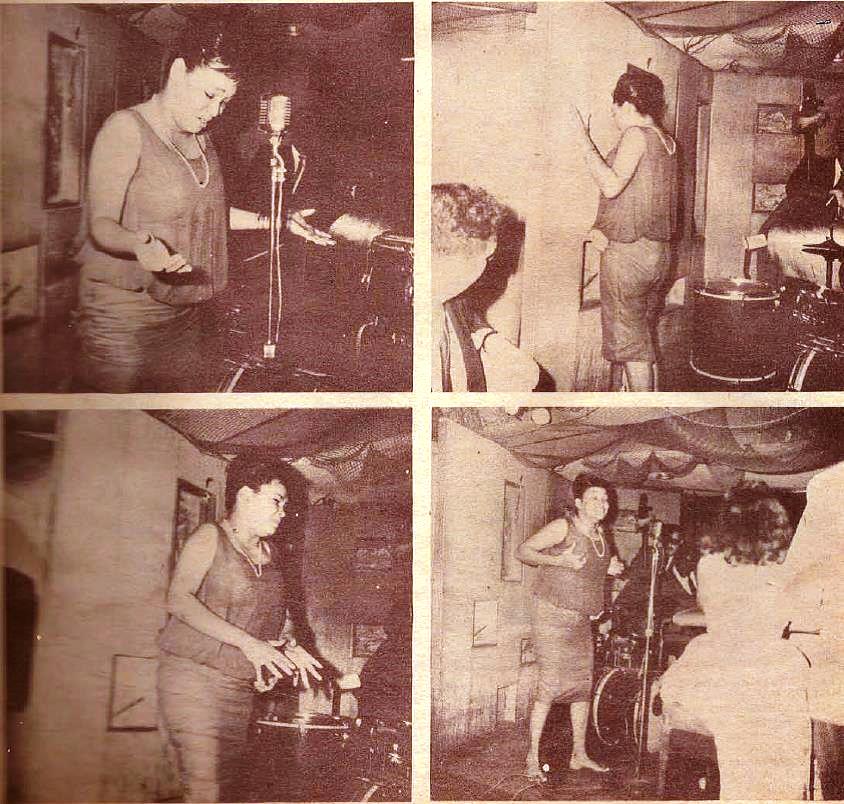

One of the most extraordinary myths of Cuban entertainment had been born, of unexpected lasting in the Cuban popular imagination. Suddenly and without prior warning, La Lupe managed to direct all eyes and also steps towards La Red to listen to her in fiery and challenging boleros, and even unprecedented congas and within the four walls of that basement, all seasoned with an unprejudiced delivery, visceral and without referents in the immediate Cuban music scene. The performance of La Lupe in the small stage of that basement turned into a nightclub would place it forever on the map of that ghetto of music and entertainment that that area of El Vedado became at the beginning of the 1960s, and La Red would forever remain impeccably linked to the name and myth of La Yiyiyi: it was there that the beating of her fine high-heeled shoes on the resigned shoulder of her pianist-martyr Homero Balboa would become famous; it was there where she would stick to the wall, like the ivy to which she sang exalted, where she died each night and was reborn in each song. It would be the scene of her definitive reputation in her country. It would seem that that forceful and clear voice was not enough for it, and that she needed to deploy all the weapons of her temperament to feel that her dedication was complete: “she waves her hands like a possessed woman and begins to moan, to shout, to curse, to literally fall apart in the ecstasy of a song.…”11

Even passing travelers came to see her incredible performance, her show of high heels and frenzy: Ernest Hemingway, Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Tennessee Williams, and there are those who say that even Marlon Brando and Gerard Phillipe were abducted by the La Lupe phenomenon.12 They say that the then Soviets Mikhail Kalatozov and Evgeni Evtushenko also saw her at La Red and, although it did not happen in the end, they valued her possible inclusion in the film Soy Cuba. Her repertoire could be classified as pleasantly disconcerting, since she made people shudder with the reproaches of “No me quieras así,” by Facundo Rivero, or surprised with his way of taking on the song “Ódiame,” by Rafael Otero, or astonished with her personal version of the international hits of the moment, “Fever” (Cooley-Davenport) and “Crazy Love” by the then object of youthful adoration Paul Anka, or stunned the spectators of her theatrical rendition of the calypso “Con el diablo en el cuerpo,” by Julio Gutiérrez.13

In the words of critic Rafael Casalins, “La Lupe sings like no one had done before, and she declares with a shrug: ‘I sing as it comes to me.’ And like her, no one had thought of it before. Her repertoire is inexhaustible: whether she physically melts into the sweetness of a bolero, which she sings like one of the carnival street dancers, or lets herself die feeling that looks like a Spanish jota with mulatto blood. Lupe dances with a Cuban flavor that Ochún has given her: she dances with her whole body, because she dances with her soul. She sings with the fury of one who sinks into a pagan rite.”14

Echoes of the fascination for La Lupe had reached the management of the Capri Casino and in June they decided to hire her as the first star of the prime time show, with all the usual luxuries and privileges, where she performed with great success from her first night, but she did not stay long in the cast of what was then the first cabaret in Havana: some say that so much pageantry was alien to her; that she did not feel comfortable continuing to throw stools, cursing at this one and joking with that one. Others, like some media outlets, were quick to affirm that her demand to increase her fees to 200 USD per week, instead of the 100 for which she had been hired, had not prospered.15 In any case, the diva returned to her small stage at La Red club, where he reigned with all the attributes of her wild and popular royalty.

The polarization of opinions around the La Lupe phenomenon had already begun. Venturing to show her beyond the meager perimeter of La Red club, or the lavish Capri Casino and making her appear on radio and television, ended up generalizing the controversy. In truth, perhaps at that time La Lupe must have been an artist not for the general public, but for that group of beings in a state of grace who could understand her dedication, which, by the way, was more and more adjusted to her own state of mind “To see La Lupe, you have to see her ‘live,’ without censorship, in her unique ‘nature,’ which is expressed through a devilish set of gestures and words like arrows. It doesn’t matter who has sung a song before her, she manages to make it be forgotten and recreates it, looking for variations that the number didn’t have, as in the case of ‘No me quieras así,’ which the public has baptized as ‘La Pared’ after hearing it by La Lupe, because she interprets it reclining on a wooden platform. Others think that her climax number is ‘Juguete’ and another one, that it is ‘Las Jardineras,’16 a fiery conga from the same Santiago de Cuba neighborhood where La Lupe launched the first of her famous howls. With so many different opinions, the uproar created in the room when she starts to sing is something incredible. Everyone asks for their song, but La Lupe’s unusual sense of rhythm turns even the noise into music: she takes advantage of it to start clapping, which the spectators do little by little with her, and, without realizing it, she has formed the prelude to ‘Quiéreme siempre.’”17

To a great extent, Lupe’s success was supported by a part of Havana’s intelligentsia and its followers who, let it be said, in those years were at the mercy of dissimilar foreign influences, among them, the existentialism of Jean Paul Sartre, and his positions on assuming art as a personal commitment, which led them to bet on figures they considered, as transgressors of a certain established order, paradigms of absolute uniqueness and creative value, as was the case of La Lupe. Relevant figures — each one in their own — such as Miriam Acevedo, Antonia Rey, Fausto Canel, Odalys Fuentes defended the singer’s style. Canel even stated that we were in the face of “the most attractive night show in Havana.” Famous journalist and writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante, then still in Cuba, was of the opinion that Lupe gave the impression of a psycho-somatic personality.18 Entertainment critics went to extremes in judging Lupe Yoli Raymond, and clashed on the same pages of the newspapers from completely opposite positions. In addition to Segundo Casaliz, also from the pages of the newspaper Revolución, Luis Agüero, for example, in his Audiovideo column in the same newspaper stated: “Confronting Lupe is confronting a totally unsuspected phenomenon. La Lupe sings like it was never imagined one could sing (biting her hands, pinching her breasts, kicking a chair, hitting the cymbals). La Lupe has gotten too far ahead, hence the nervousness she provokes at the first meeting. The columnist knows that many will fight La Lupe. Coincidentally, when I was writing this comment, someone said that La Lupe was ‘the anarchy of music.’ The definition, in addition to being inaccurate, is unfair. Orlando Quiroga has said that the ‘strong words’ that La Lupe says, that is, the bad words, are intended to shock the bourgeoisie. And unless La Lupe’s swear words shock bourgeois and non-bourgeois alike, the observation is wrong. All the elements that La Lupe incorporates into her songs (the bad words, the moans, the bites, the rude signs), have a single objective: to illustrate the song as accurately as possible, even if it is necessary to resort to pornography. All of the above has no other reason than to try to explain her phenomenon, which is impossible to explain. And also, to establish the position of [the column] AUDIOVIDEO: Defending La Lupe, the most powerful artistic event that has occurred in a long time.”19

And it is that Orlando Quiroga, one of the most reputable critics, was slow to understand the essence of the La Lupe phenomenon and assumed at first, presumably, a position of harsh criticism from the pages of the Tele-Radiolandia section in the magazine Bohemia, which, by the way, did not appear signed. As an example: “La Lupe appeared again on television. She did it on the ‘Fin de Semana’ program, which [Armando] Roblán hosts. If you’ll pardon those who have turned La Lupe into a kind of sacred monster, it seems to us that she has very little to contribute to our screens. As a transient and ‘clownesque’ phenomenon it was fine. But once the public’s curiosity is satisfied, all that remains of La Lupe is, for ordinary viewers, who are the majority, an absurd and schizophrenic style of singing. And if because of that they question our critical judgement, what can you do about it?”20

Quiroga was not the only one: another insidious criticism would appear months later, from an uncomfortable anonymity, in the pages of the newspaper Revolución: “Her performances are disastrously inappropriate and unpleasant, completely opposed to good taste and lack the slightest expression of art. La Lupe is like a public threat and defending her is almost a sin.”21

However, for many it was clear that Lupe Yoli, as well as Freddy, was the bearer of an authenticity unknown in Havana nightlife, something organic and legitimate, but unexpected and therefore, she already had legions of followers and fans willing to defend her right to this unusual mode of expression, “a more adult public that wants intelligent artists, and not silk and rag dolls, for the ravaged taste of superficial tourism…,” as stated in an important anonymous comment in Bohemia magazine.22

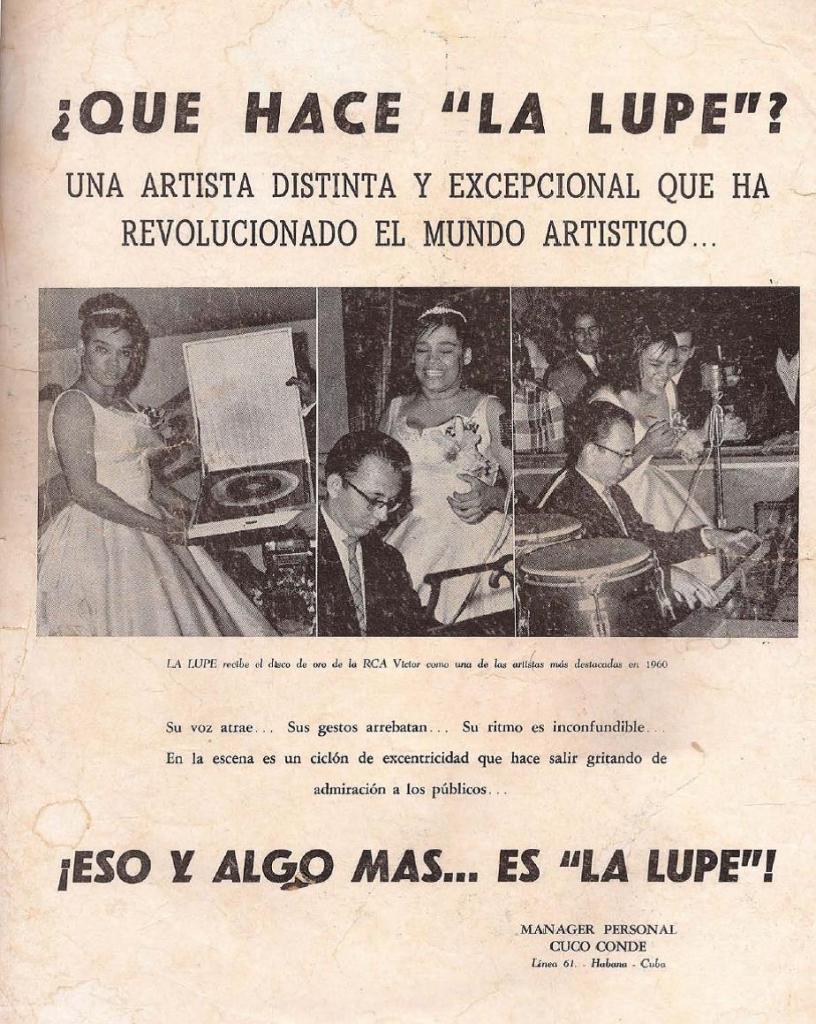

The Cuban record industry reacted quickly to the unusual success of La Lupe: through the manager for Cuba, Eliseo Valdés, RCA Víctor offered the diva an exclusive contract for the recording of her first long-playing album, as was announced in Show magazine in its September 1960 issue, which also highlighted the conclusion of the agreement in the recording, initially, of a 45 rpm disc with the songs “Quiéreme siempre” and “Fiebre.”

In October 1960, she appeared in a musical revue at the Estrada Palma theater (later Nacional) together with Venezuelan Héctor Cabrera, who was extremely popular in those months in Cuba due to his success with the song “El Pájaro Chogüí” and others. The press in general considered the passage of La Lupe through the Prado Coliseum as a confirmation of her popular roots, although Show magazine assured that her debut on stage was not entirely successful and did not satisfy the public,23 while she continued to generate inflamed controversy by both signs on her presentations in nightclubs and television. That same month she declared to the magazine Bohemia that she was not going to accept any contract to appear abroad before December 31, “if I’m still of interest,” she added modestly, and affirmed that she had twelve different proposals.24

The reviews of the year 1960 in the media, pointed her out among the five most outstanding revelations of the period, along with Eduardo Davidson with the overwhelming success of his song “La Pachanga”; singer Pacho Alonso, the vedette Nelly Castell and Roberto Blanco.25

She had also managed to be part of the important list of exclusive artists of RCA Victor and also of those managed by the famous Cuco Conde, who had become her personal manager. Her LP record Con el diablo en el cuerpo, the first, quickly and in a very short time reached exceptional levels of sales, to the point that in February 1961 she was given, with great publicity, the gold record of the RCA Victor, as one of the most outstanding artists in 1960, for her hit “Quiéreme siempre.”26 She was accompanied on the lineup of those awarded with gold records, by none other than Benny Moré and Pacho Alonso and bolero singer Luis García and the Aragón orchestra, that label’s exclusive artists. For the ceremony, the management of RCA Víctor chose La Red club, the site of Lupe’s greatest hits. She was among the greats of the moment, and if one had to summarize it would have to be affirmed that 1960 was in Cuba, without a doubt, La Lupe’s year.

At the beginning of 1961, the local Discuba label associated with Victor at that time, announced — and the press highlighted — the release of another long-playing record of she who they called “the most eccentric singer in Cuba.” It would be the last of the only two LPs the diva recorded in Cuba and whose master tapes managed to be preserved, according to information from the EGREM recording company, in its historical archives, although this second album, apparently, was not distributed in Cuba. The first recordings of her greatest hits from her early solo days were made in Cuba, not New York.

In April, Show magazine, the most important in the world of entertainment in Cuba, gives her an award for the triumphs she has achieved during the year she has been at the La Red club, and in September, in a celebration held at the Le Mans club — where she was performing regularly and which her partner at the time, Pedro Pacheco, was in charge of —, created a category especially for her and proclaimed her “the eccentric singer of the year.” She does not escape reflection, that such classification did not take into account her possible — actually real — vocal virtues, but essentially her singular scenic and performative projection that, without hesitation, capitalized the attention towards the La Lupe phenomenon. Regarding Yiyiyi’s impact on Havana’s nightlife and on the music scene at that time, Show magazine commented: “It was one of the prizes we award to those who turn out to be very characteristic attractions of the moment in which they are discerned. But the fact is that La Lupe did not stop there. Her triumphant trajectory has continued with even greater speed, already becoming an obligatory subject of criticism. She took over a cabaret that was practically bankrupt — Le Mans — and merely her name being advertised on the billboards, raised it from the ruins, causing unprecedented crowds. The Le Mans cabaret, on 5th and B in El Vedado, is irrefutable proof of how much La Lupe influences the hearts and popular admiration. Simply that her style created by and for La Lupe — because it is unique — places her in the artistic classification as the eccentric singer of Cuba.”27 Indeed, in the same year, La Lupe revived two nightclubs in clear decline — La Red and Le Mans —, placing them at the zenith of nightlife. However, near the end of 1961, the diva left Le Mans, when the management of the establishment changed. For the second time, she received the Show magazine’s trophy for Best Eccentric Singer — although everything seems to indicate that she left little room for others who wanted to imitate her and had no opponents — and her photo singing at Le Mans earned photographer Fernando López the Photo of the Year award.

In 1961 the contradictions between the nascent Cuban Revolution and the government of the United States intensify. In April the Bay of Pigs invasion took place and the complexities of the situation inside the country become more acute, including in the field of culture and entertainment. Exactly the year in which she decided to join the exodus of musicians and artists, La Lupe was neither more nor less than the very center of the Cuban media-musical hurricane, which reflected the tremendous success that she had achieved in just under two years of career as a soloist. Almost twenty months had gone by between her debut at the La Red club and her departure without return to Mexico first and then to her marked destination, New York, where there was waiting for her, after certain moments of hardship and the rigorous adjustments in the face of the arrival in an unknown country, a success similar to the one achieved in a short time in Cuba, but greater because of the comprehensiveness of her imprint on the history of Latin music, because of its unquestionable international repercussion. Perhaps Lupe Yoli, the one who loved the rainbow —it was not for nothing that she lived in a Havana building with that name and how she named her daughter, Rainbow — in English — didn’t know what to do with that Havana conquered for better or for worse, the city where for the first time, fame became a fascinating and cursed lure for her, the Havana that would have seen the emergence, perhaps, of the tragic sign that marked her entire life: the dilemma in the face of extreme situations and her inability to promote or make the best decision in her favor. Probably, the antagonistic extremes of the controversy surrounding La Lupe and the uncertainty of the months to come ended up frightening her and perhaps, from her small space in La Red, Lupe Yoli was certain that hers would never be a normal and happy life. When she left Havana, never to return, she couldn’t imagine all the good things that were coming her way, that she would hold the throne of Latin music, or that she would touch the glory of fame. She, too, must not have imagined that with her outlandish and outgoing style she had begun to build one of the most persistent and universal myths of Latin music of all time.

*Thanks to Rodulfo Vaillant and Enrique Pineda Barnet for their collaboration.

**This text was originally published in Desmemoriados. It is reproduced with the express authorization of its author.

Notes:

[1] “La Escala de la Fama, programa de la CMKW obtiene nuevos éxitos.” In Radiomanía y Televisión. Year 19. No. 4. April 1955. Page 30. Also in the same magazine, Year 19 No. 5, May 1955. Page 34

[2] Radiofónicas Orientales Section in the magazine Radiomanía y Televisión. Year 19 No. 7. July 1955. Pp. 48 and 49

[3] Taken from: Radamés Giro: Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Música Cubana. Letras Cubanas publishers. Volume III. Page 45

[4] In the name of “Tina” it has been taken from the voice dedicated to La Lupe in the Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Música Cubana (Volume 3, Page 45), by Radamés Giro.

[5] Show magazine. Year 5. No. 56. Page 54. October 1958.

[6] Show magazine. Year 5. No. 57. Page 74. November 1958.

[7] Show magazine. Year 6. No. 64. June 1959. Page 60.

[8] Bohemia magazine. January 3, 1960. Teleradiolandia Section. Page 108.

[9] Show magazine. Year 7. No. 74. Page 49. April 1960. Page 49

[10] Rafael Casalins: “La Lupe.” In newspaper Revolución. 4.7.1960. Havana Cuba.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Radamés Giro: Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Música Cubana. Letras Cubanas publishers. Havana, 2007. Vol. 3. Page 45.

[13] Adriana Orejuela: El son no se fue de Cuba. Letras Cubanas publishers. Havana, 2006. Page 155

[14] Rafael Casalins: “La Lupe.” In newspaper Revolución. 4.7.1960.

[15] Show magazine. Year 6 No. 79. Page 67. September 1960. Page 33.

[16] This assertion about the Havana carnival street dancers does not seem to be exact (Author’s note)

[17] “Lupe: un caso sico-somático que divide en dos a Cuba.” Unsigned article in: Bohemia magazine. Year 52 No. 43. October 23, 1960. Havana. Page 86.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Revolución newspaper. 9.7.1960. Audiovideo section. Page 14

[20] Bohemia magazine. Teleradiolandia section. 5.3.1961.

[21] Revolución newspaper. 20.9.1960. Page 15

[22] Bohemia magazine. “La Lupe. Un caso sicosomático.” 10.16.1960. Page 86.

[23] Bohemia magazine. 6.11.1960 and Show magazine. Year 6 No. 81. November 1960. Page 24.

[24] Bohemia magazine. Havana. Cuba. 30.10.1960.

[25] Bohemia magazine. Year 53 No. 7. 12.2.1961

[26] The LP “Con el diablo en el cuerpo” would be distributed under the local DISCUBA label, also controlled by RCA Víctor. (Author’s note)

[27] Show magazine. Year 7. No. 101-102. October-November 1961. Page 28.

The documentary “Lupe: Queen of Latin Soul” by Cuban-American filmmaker Ela Troyano has also been an important reference in this investigation.